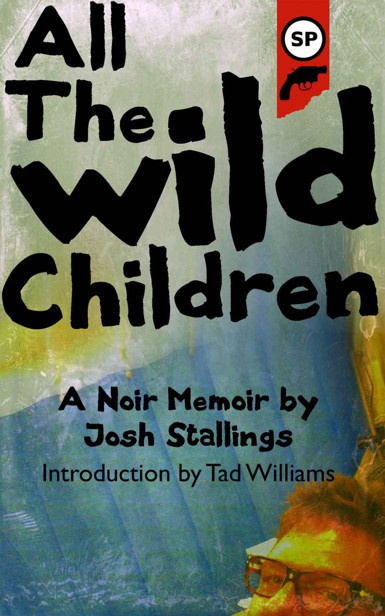

All the Wild Children

Read All the Wild Children Online

Authors: Josh Stallings

ALL THE WILD CHILDREN

JOSH STALLINGS

All the Wild Children by Josh Stallings

Published by Snubnose Press at Amazon

The copyright belongs to the authors unless otherwise noted. 2013. All rights reserved.

Amazon Edition

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locations is entirely coincidental.

FirstAmazon Original Edition, 2013

Cover Design: Eric Beetner

Amazon Edition, License Notes

All rights reserved. This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Amazon.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author

"

Josh has done an incredible job with the hand life dealt him. I admire the hell outa that. All the Wild Children is simply Stunning." -

Ken Bruen

"What is most remarkable about All The Wild Children isn't the rhythmic fleetness of it's earnest prose, nor the relentless pace, nor the fantastic nature of its plot, nor, even, the fact that it is all true. What is most remarkable is that Josh Stallings managed to survive malicious fate, addiction, and the belligerent idiocy of his youth, and somehow find some dregs of fortitude remaining that allowed him to put it all on the page with a rare degree of honesty; willingly admitting that truth is fleeting and that this is no more than his best recollection of the storms and what they left behind. Laughing in the face of brutal misfortune and epic poor judgement is a tonic. One that Stallings graciously invites us to imbibe with him. Drink up. God knows Josh did." -

CHARLIE HUSTON

“Someday, this will read much better than it lived.” -

Lark Stallings (1975)

What you are about to read is at best the recollections of a man with a weak memory but a strong sense of what it felt like. Truth is personal. We are all the heroes of our own narrative, this is mine.

This book is dedicated to Larkin, Shaun and Lilly. Strong feral children and brave and honorable and if given a choice they are the three I would have gone through our mess of a childhood with.

INTRODUCTION by Tad Williams

Every word that Josh writes in this book is true. I tell you that not just because I witnessed and participated in many of the events, but because that's who Josh is -- he's compulsively honest. People who are afraid of themselves often are. Honestly, he's one of the world's best humans, but he doesn't seem to know that. He won't even believe it when I write it here for everybody to see.

The parts of Josh's story I experienced were all in the 1970s, when we invented irony. By we, I mean the kids that grew up in the years after the great explosion of the counterculture. When I say we invented it, I don't mean the concept or even the practice, but that it was our generation -- disgusted by The Establishment but also annoyed by hippie optimism -- that made it the cultural norm. (And now the snotty global language of the internet era. Sorry about that, world.)

We were experimenting heavily with drugs and drink and sex, of course, but in the particular circles in which Josh and I ran, we were also deep into scenarios and identities. Maybe we were waiting in a trough between cultural waves, in a sense, waiting to see what the next curl was going to be. In any case, we took what was there, weaving an identity for ourselves out of suburban snarkiness, Black and gay culture, theater, pre- and post-punk attitudes toward the mainstream and "ordinary people", and a reverence for Hunter S. Thompson and his works.

When you're older you can see how all of the decades have passed and how they've each changed you, but when you're a child becoming an adult, what's in front of you is the only game in town. For better or worse, you have found your social milieu. It will surround you for the rest of your life, get name-checked in nostalgic discussions, jump out of car commercial soundtracks like an aged showgirl out of a cake.

We came along after the hippies, and in some cases they were parents of ours, or at least zoned-out older siblings. We didn't mind the zoned-out part so much, but we didn't want to escape society, we wanted to control it -- or, failing that, live in it free and unfettered, like happy anarchist rats in the walls. I don't remember worrying once about how I would make a living, even long after the age I should have been aiming toward something. It wasn't because I thought anyone else would support me, my parents or the government. I just felt confident that I'd eventually be able to find a way to live while doing what I loved. Astonishingly, it worked out. Not everybody's dream did. We were a generation who had many disappointments later, friends and heroes dying from the twin plagues of drugs and AIDS, but we started when people were still playing folk-rock on the radio and singing about sunshine and giving peace a chance.

So when Josh talks about his dad leaving, he's also telling you about a personal time that a whole generation experienced in a larger sense, where we 70s kids consciously stepped away from the more outwardly radical lifestyles of our immediate elders and back toward the mainstream, but with the distinct idea of ourselves as not having given in. We were secret agents, moles, almost, by our own definition -- in society but not of society.

A lot of that was bullshit, of course, to excuse ourselves for not being as radical and active as the preceding group of youth. And a lot of what we felt was unique was the same stuff all groups of young people feel. But even if people as a whole remain much the same from generation to generation, society itself changes, and we were born into a great deal of change, Peace and Love versus the Cold War. I think that defined us all, even the kids who had less interesting childhoods than Josh did. From the start, we walked on shaky ground.

But one of the things we did take directly from the 60s folks who preceded us was that we believed life should also be fun -- interesting and unexpected fun, not just picnics and church socials and team sports. We were actors and artists and musicians in the suburbs and had to make our own excitement, so it could get pretty creative. It was also part of trying on new identities. When Josh tells how we once pretended to be English musicians (for weeks and weeks) it's not just about fooling some cute girls into thinking we were cool (although it was certainly about that) but also about the unspoken idea that, in some sense, we could be anyone we wanted to be. That brains and balls and a sense of humor could make anything happen. (That list is metaphorical, by the way. I knew lots of women back then, including Josh's sisters, who were ballsy as hell.) That idea of "anything is possible" cut both ways, of course. You can start a company in your garage that will change the world, but you can also watch your parents give up on being parents and decide to try something new with their lives.

Anyway, whatever else had happened in the preceding ten years -- call it 1963-1972 -- we young people of the next decade felt that nobody was going to force us back into a social mold again, not without a fight. That principle we absorbed from our elders. That we took to heart.

Less certainty and more freedom. I guess that's what was at the heart of our brief moment, when we were the young in-crowd. We had an almost unlimited set of possibilities laid before us. Not all of us made good decisions, of course, and some of us never recovered from the bad ones. But Josh, like many of us, managed to survive that unfortunate period many of us go through, when we think we can outlive anything, or stop caring whether we do. He came out the other side. But he also paid attention while he was there, and as you'll see when you read this book, he thought a lot about how to take the good and bad and make it all into something significant.

He did, too -- both in his life and in this very, very fine story about his life.

“

Scars have the strange power to remind us that our past is real.”

Cormac McCarthy,

All the Pretty Horses

FROM THE DAY ROOM OF A MENTAL HOSPITAL

I am 50, and I am sitting in the day room of a mental hospital. The world around me is

muted colors. Scuffed white floors and walls. Pale green scrubs. The dayroom is full. Brown skin, light skin, crazy is democratic. Men, women, in between, crazy takes no sides in the gender war.

Crazy takes casualties.

Crazy takes prisoners.

Crazy is the woman rocking back and forth wrapped in her Snoopy blanket, her once blonde hair matted thick as any dread.

Crazy rails.

Crazy cries softly.

Crazy is my son.

His eyes come briefly into focus. He looks around at the damaged inhabitants of the day room and then at me. His eyes ask,

how did I get here?

And I wish I knew. So I start to write this book. I think it is about my son. I know it is about much more.

I am 5, watching my older brother Lark as he kneels to say his prayers, he is seven and my best friend. He speaks to Jesus. I think he must be faking it when he prays, because I am. Or maybe he really does hear God’s voice. Maybe God talks to him because he likes Lark better than me.

I am 6, my folks are at each other again. Their screaming is part of the background noise of my life. Like traffic in the city only this noise you don’t get used to.

I am 7, and my father is yelling at my mother. She screams back. I stand between them and rage, “You told me God doesn’t want us to fight, so why are you!” Good Quaker logic I think. I'm thrown against the wall. My father’s hand on my throat. Pinned.

I am 50, and wonder why I still feel the grip of that hand.

I am 7, and my father’s angry hurt eyes beg me to back down. Beg me to give an inch so he can let me go and hug me without admitting a child’s victory over him. The trouble is. Always is. I’m not capable of backing down. Born without a reverse gear. A cornered raccoon will try to kill a dog three times its size. I know this because I’ve seen it. The dog was mine. A cornered raccoon has only two choices, die or kill. No white flag. No calling uncle. My dog wasn’t as committed to the battle - he thought walk away was an option. He was wrong. If not for a rifle bullet through the raccoon’s heart, my dog would have died that night.

My father holds me pinned. I can smell the tobacco on his breath. My jaw sets and I will not cry, not with my back to the wall.

My father looks in my eyes and knows he must kill me or walk away. He walks away.

I am 8 and my father no longer lives with us. We move from the country to student housing at Stanford. Our eighteen acre back yard becomes a patio. My brother and I share a room. A blessing. My sisters, who are separated by six years, share a room. A curse. In one summer everything we know changes. I learned early not to trust change. The mother goes to grad school and works. The father works nights, sleeps days, dates a stripper. We kids raise each other the best we know how. Later we will say we were raised by wolves. Wolves that loved us, but wolves none the less.

This is the new normal.

Inarguably.

Get used to it.

Of course this is an over simplification of a childhood.

It had good and great and awful days. Some days my mother was there. Some days my father took us to the park. Some days my little sister Shaun and I would play in a drainage ditch and mak

e

clothes fo

r

fairies out of pounded algae. My brother and I will go to high school in the ghetto. We will carry guns. We will sell drugs. We will creep houses. We will fall in love. We will get laid. We will survive. At sixteen, Lilly my older sister will have had enough. She will move to L.A. She will shoot dope. She will strip for a living. She will give me my first David Bowie album. At sixteen I will go to L.A. and study acting.