Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War (25 page)

Read Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War Online

Authors: Tanya Harmer

Yet amid rumors of military plotting against Allende in late 1971, the CIA got cold feet. True, U.S. intelligence had drastically improved and could now count on a collection of agents within the armed forces along with daily information on plots against Allende.

117

But when CIA station officers proposed encouraging such plotting by working “consciously and deliberately in the direction of a coup” and establishing a “covert operational relationship” to discuss the “mechanics of a coup” with “key units,” they received a negative response.

118

With no approval from higher authorities,

and fearing the negative implications of a botched coup attempt both in Chile and beyond, the chief of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division, William Broe, definitively curtailed the station’s actions. “We recognize the difficulties involved in your maintaining interest and developing the confidence of military officers when we are only seeking information and have little or nothing concrete to offer in return,” he wrote. “There is, of course, a rather fine dividing line here between merely ‘listening’ and ‘talking frankly about the mechanics of a coup’ which in the long run must be left to the discretion and good judgment of the individual case officer. Please err on the side of giving the possibly indiscreet and probably uncontrolled contact little tangible material with which to accuse us.”

119

It was this fear of being accused of intervention—a particularly sensitive concept in late 1971 U.S. domestic and international contexts—that led the United States to hesitate. As Under Secretary Irwin summarized, the key was “to allow dynamics of Chile’s economic failures to achieve their full effect while contributing to their momentum in ways which do not permit [the] onus to fall on us.”

120

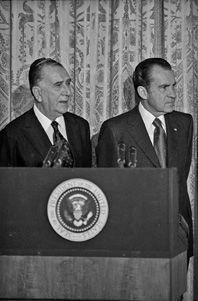

Emílio Garrastazu Médici and Richard Nixon in Washington, December 1971. Courtesy of Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

Crucially, Chilean diplomacy in late 1971 had made this task more difficult as it made U.S. actions against Allende more visible. While Letelier’s

suggestion that the United States was merely “playing a policy of equilibrium” was clearly misguided, he was right in suggesting that the weakness of Nixon’s position in Latin America, U.S. domestic politics, and the Third World continued to limit the United States’ flexibility when it came to opposing La Vía Chilena. Chilean policies also bolstered Kissinger’s predilection for interpreting the global balance of power in broad conceptual, as opposed to material, terms. Together with the majority of Nixon’s foreign policy team, he consequently believed that the United States had to restrain its impulse to fight openly against Allende and to speed up efforts to “bring him down.” Given the international environment of late 1971, a divided administration therefore proceeded with cautious determination to transform the direction of Chilean and inter-American politics and to warn Third World nationalists not to follow Allende’s path. As it turned out, and for reasons not exclusively connected to the United States or its destabilization campaign, the dynamics of Chilean domestic developments were actually moving in the United States’ favor. By the end of 1971, U.S. policy makers could point to a range of factors causing Allende trouble at home and threatening to undermine his peaceful democratic road to socialism. From November onward, these included not only the cost of the UP’s economic policies and the growing polarization of political forces but also the impact of Castro’s extended tour of Chile.

Fidel Castro had received a clamorous welcome when he landed in Santiago on 10 November 1971. One Chilean Communist Party member recalled her “heart nearly ripped in two” as she watched Fidel drive by, and even unsympathetic bystanders came out onto the streets to catch a glimpse of Latin America’s most famous living revolutionary.

121

The visit was not only a clear affirmation of the evolving ties between Havana and Santiago but also an obvious turning point in hemispheric affairs. Cuba seemed to have formally returned to the inter-American system, and Castro described his trip as “a symbolic meeting between two historical processes.”

122

As Allende proclaimed, Chile and Cuba stood on the “front lines” of Latin America’s struggle for independence, constituting “the vanguard of a process that all Latin American countries” and “exploited peoples of the world” would eventually follow.

123

Before Fidel’s arrival, he had also proudly noted that in one year the Chileans had done “more than the Cubans did during their first year of the Cuban Revolution.” While his comment was “not intended

to the detriment of the Cubans,” he did say that when Fidel arrived he would “ask him” what he thought. “I know what the answer will be,” Allende had confidently predicted. “Let it be known for the record that we made our revolution at no social cost.”

124

When indeed asked to comment on whether Chileans had done more than Cubans in their first year, however, Castro had demurred, arguing it was “completely inadmissible” to make such comparisons. Instead, he said that in Chile the process was much more “tiresome and laborious,” pointing out that whereas the whole Cuban system had collapsed in 1959, the revolutionary process in Chile was still developing and faced more obstacles.

125

Indeed, if Castro was hopeful when he arrived in Chile, he left preoccupied, and Cuba’s Chilean policy underwent a considerable shift as a result. Instead of confirming Allende’s achievements, the visit also seems to have magnified his difficulties. During his stay in Chile, Castro openly indicated that he thought revolutionary transformation needed speeding up, that there were merits to using violence to advance this transformation, and that Allende bestowed too much freedom on his opposition. In Fidel’s view, a confrontation between “Socialism and Fascism” loomed on the horizon and if Chile’s left-wing leaders did not take his advice, they would not survive it.

By the time Castro touched down in Chile, governmental and extragovernmental ties between Havana and Santiago had grown substantially. At a ceremony to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Bay of Pigs in April 1971, the Chilean Embassy in Havana had reported that Castro and his audience seemed to be celebrating Chilean developments rather than Cuba’s revolutionary victory.

126

On this occasion, the Cuban leader also meaningfully pledged Cuban “sugar … blood, and … lives” to help Chile’s revolutionary process.

127

Chile had clearly become a celebrated cause in Cuba and the focal point for cultural, economic, and social exchange projects to such an extent that by the end of 1971 state-approved collaborative projects had been established in the fields of cinema, agriculture, fishing, housing, mining, energy, health provision, sport, and publishing. In addition, the University of Havana now had formal links with five separate Chilean universities.

128

Bilateral trade between Cuba and Chile had also grown. Whereas the UP had spent $13 million on Cuban imports in 1971, it proposed to import $44 million worth of sugar in 1972. Cuba also agreed to increase the value of its Chilean imports to just over $9 million (which would include 100,000 cases of wine despite the Cuban population’s preference for rum).

129

What

is more, in June 1971, Cuba’s national airline had begun direct flights between Santiago and Havana, and around the same time the Cubans had also approached the Chileans enthusiastically regarding the possibility of joint mining projects. (Cuba’s minister for mining, Pedro Miret, had explained that the Soviet bloc lacked expertise and had not been very forthcoming with technical assistance but that Cuba was interested in increasing mining production.)

130

However, trade figures demonstrated a stark imbalance and the incompatibility of the two countries’ economies. The UP’s growing financial difficulties were also increasingly limiting the scope of this blossoming economic relationship. Indeed, at the end of 1971, earlier optimistic estimates for Chilean exports were already being scaled back. For example, the Chileans had to acknowledge that they would be able to provide only 150 of the 2,000 tons of garlic that they had offered months before.

131

Irrespective of these trade difficulties, Havana and Santiago had already reaped tangible benefits from the evolving diplomatic relationship between them. Foreign Minister Almeyda had abandoned relative caution at the UN General Assembly when he proclaimed that Chile would work tirelessly to overturn Cuba’s isolation.

132

Havana had also been able to reestablish better links with Latin America through its embassy in Santiago. Not only did Havana’s communication with Latin American revolutionary movements in the Southern Cone improve, but the Cubans also began developing economic relationships in Argentina and Peru. From 1971 onward, for example, Cuban representatives began making secret trips across Chile’s borders into these countries with Allende’s knowledge and with tacit support from Argentine and Peruvian authorities. Private Chilean companies also provided a channel for Cuban purchases in the outside world (Castro’s Cuba even managed to purchase Californian strawberry seeds through a surrogate Chilean business whose crops were eventually destined to serve Cuban “Copelia” ice creams).

133

Allende’s government also benefited from the more covert side of its relationship with the Cubans. At the beginning of 1971, the UP had begun to discuss how it would respond to a coup if one were launched against it. Although the government was divided on the issue of military preparation, testimonies of those involved indicate that basic contingency plans were revised both by those who supported some form of armed struggle and by those, such as the Communist Party’s leader, Luis Corvalán, who dismissed its relevance for Chile. Allende’s constitutional commander in chief of the army, General Carlos Prats, also appears to have seen the plans, and his

participation in any effort to thwart a coup was considered pivotal. Beyond these tentative moves, the Socialist Party had approved the creation of an organizational “Internal Front,” a “Commission of Defense” with a military apparatus and intelligence wing, and a commitment to strengthen the president’s bodyguard at the beginning of the year. Together, members of this new defensive structure concluded that a peaceful democratic transition to socialism was unlikely and that confrontation was probable. They also observed that the armed forces increasingly believed they had a political role to play in the country and that, as a result of all these factors combined, it was unlikely the UP would complete its six-year mandate.

134

Ever since Allende’s direct request for Cuban security assistance in September 1970, the Cubans had been helping the Chileans by collaborating with their intelligence services and arming Allende’s bodyguard, the GAP.

135

As one of the MIR’s leaders later recalled, the Cubans helped turn the GAP into an “organized military structure” with “schools of instruction,” and he admitted that the MIR took advantage of these schools to train its own cadres surreptitiously.

136

Beyond the GAP, the Cubans would also separately train and arm sectors of the MIR, the PS, the PCCh, and MAPU during Allende’s time in office. Although the numbers of those trained varied considerably when it came to the different parties (with the PCCh’s and MAPU’s numbers being considerably smaller), this support was offered with Allende’s knowledge.

137

The president’s private cardiologist would later recall that the Cubans also gave him a Browning pistol so that he could step in for the GAP in times of need. (During Allende’s trip to Colombia, for example, he had smuggled the gun nervously into a presidential banquet when the GAP was refused entry.)

138

Although the CIA did not know the precise quantity of arms delivered to Chile, it knew enough by November 1971 to be able to inform Langley that the GAP’s “Cuban-provided” pistols had completely replaced what had been a “haphazard collection of sidearms.”

139

The CIA also reported that thirty Chileans were already receiving training in Cuba “at the Cuban department of state security school,” with another thirty being recruited to join them. And, overall, the CIA concluded that this evidence suggested the Cubans were helping to create a “substantial guerrilla force” in Chile.

140

Indeed, the new information that the CIA had on Cuban operations by late 1971 meant that it abandoned its policy of fabricating stories of Cuba’s role in the country and began passing “verifiable” information to Chilean military leaders.

141

Besides indications that the Cubans were delivering weapons to the Chileans,

Allende’s relationship with the MIR came under scrutiny, just as the CIA had hoped it would. In August the brief rapprochement between the MIR and the PCCh had begun disintegrating.

142

The MIR was also excluded from the GAP after its members were found to be stealing the bodyguards’ arsenal for its own purposes.

143

The GAP’s principal Cuban instructor, a member of Cuba’s Tropas Especiales by the name of José Rivero, seems to have precipitated this crisis. By secretly colluding with the MIR, which he was especially and personally sympathetic to, Rivero had also gone against the instructions he had been given by his Cuban superiors to work first and foremost for the Chilean president and the GAP. Understandably, Allende was not happy when he learned about his duplicitous role. Upon hearing about Rivero helping the MIR to take arms from the GAP for its own purposes, he summoned Cuba’s ambassador, Mario García Incháustegui, to complain and demand that Rivero be removed from his position. As one of the MIR’s leaders recalled decades later, Rivero was not only removed because Allende requested it but also personally reprimanded by Fidel Castro for having sided with the MIR over the interests of Allende’s personal escort and the maintenance of harmony between the MIR and the PS.

144

Indeed, despite not having any idea what was behind it, CIA sources noted that Havana supported the restructuring of the GAP, which now comprised PS militants only.

145