Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War (26 page)

Read Allende’s Chile and the Inter-American Cold War Online

Authors: Tanya Harmer

Even if the Cubans acted to alleviate the crisis, a U.S. informant nevertheless reported that Allende was “very depressed feeling that the MIR would soon get out of hand, that the Armed Forces would have to be brought in to control them, and that the country may be on the brink of a civil war.”

146

On the first anniversary of Allende’s election, when the president referred to his opposition as “troglodytes and cavemen of an anticommunism called upon to defend the advantages of minority groups,” he therefore warned his supporters to unite. “Let us not permit extremism,” he warned, demanding that the Left find a common “language” to use in its fight against powerful enemies.

147

The Cubans echoed this message. In August, the Chilean press had printed Castro’s call for “true revolutionaries” to “abandon romanticism for [the] more humdrum tasks of building [the] revolution’s economic and social foundations.”

148

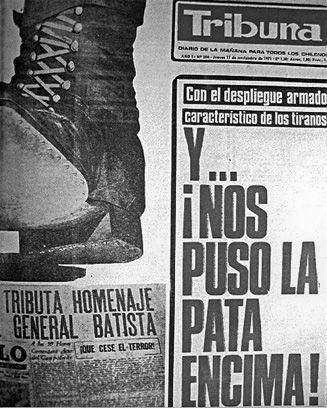

Even so, Castro’s association with Allende and Cuba’s not-so-secret involvement in forming the GAP was increasingly used against the president. Chile’s opposition press had falsely accused Cubans of assassinating Frei’s minister of the interior, Pérez Zujovic, in June 1971, and this event had radicalized sectors of the Christian Democrat

La Tribuna

, 11 November 1971.

Party and the armed forces against Allende.

149

Chilean senators also denounced the size of Cuba’s embassy. Even the British Embassy, which had a rather measured approach to Allende’s government, considered the Cuban diplomatic representation in Santiago “sinister” and “heavily weighted” toward “subversive and intelligence operations.”

150

And the right-wing tabloids began a propaganda campaign denouncing the GAP as violent assassins and warning of Cuban intervention in Chile. Indeed,

it was in this context that, on the eve of Castro’s visit, the right-wing tabloid

La Tribuna

ran front-page news that warned “Santiago Plagued with Armed Cubans” and paid homage to Fulgencio Batista.

151

Castro thus arrived in Chile as Allende’s first anniversary celebrations were turning sour. The timing of his visit had been discussed since September 1970 but had been postponed as a result of both Cuba’s domestic situation and the Cuban leader’s hope that the UP would consolidate its position before he arrived.

152

(In fact, it was six months after Allende had sent the Communist senator Volodia Teitelboim to Havana specifically to invite Castro before he arrived.)

153

Once he did, there was uncertainty and speculation regarding the visit’s length and scope within government as well as outside it.

154

Fidel’s revelations years later suggest that the trip’s duration was never his prime concern. In fact, Castro had sent Allende a proposed itinerary two months before he arrived. “You may add, remove, or introduce whatever modifications you deem appropriate,” Castro wrote, “I have focused exclusively on what might prove of political interest and have not concerned myself much about the pace or intensity of the work, but we await your opinions and considerations on absolutely everything.”

155

Of course, it is entirely possible that he quite simply never received a reply. If we judge from Castro’s subsequent stay in Chile, Allende wanted Castro’s support and approval rather than the authority to dictate the length of his stay. At a Cuban Embassy reception, Allende told the assembled guests that there were only two things he could not tolerate in life. One was a look of displeasure from his daughter, Beatriz. The other was a scolding from Fidel.

156

Even the moderate director of Chile’s Foreign Ministry conveyed his hope to the British ambassador that Castro would “be impressed both by Chilean democracy and institutions and also by the Chilean balance between the various power groups in the world.”

157

Castro used his visit to Chile as an opportunity for extensive field research, but initially he offered neither wholehearted praise nor disapproval. As a means of deepening his understanding of the Chilean revolutionary process, he spoke to government ministers, military leaders, students, miners, trade unionists, the clergy, and members of Allende’s parliamentary opposition. He visited the Chuquicamata copper mine, paying detailed attention to copper production, and spent hours discussing the Sierra Maestra campaign with fascinated naval officers while on route to Punta Arenas in the south.

158

Jorge Timossi, who worked for Prensa Latina and accompanied Castro throughout his visit, recalled that they would also meet each night to discuss the day’s events until three or four

in the morning before getting up a few hours later.

159

As Fidel insisted, he had come to “learn” rather than to teach. The Polish ambassador in Santiago also reported home after Castro’s first week in Chile that the visit was proof of Cuba’s new approach to revolution in Latin America: the Cuban leader’s relations with the Chilean Communist Party had improved; he was showing moderation and had expressed acceptance of different revolutionary processes in the region.

160

As Castro described himself to Chilean audiences, he was a “visitor who comes from a country in different conditions, who might as well be from a different world.”

161

During his visit Castro certainly encountered stark differences between Cuban and Chilean revolutionary processes. In particular, the space the UP gave to the opposition bothered him. The free press launched open and vicious attacks against Castro that included labeling him a homosexual.

162

And the unusual length of Castro’s visit also exacerbated accusations about Cuban intervention in Chilean affairs by giving criticism the space to grow. On 1 December 1971, Chilean women, together with members from the right-wing paramilitary group, Patria y Libertad, staged the first of what would be known as “Empty Pots” demonstrations, where wealthy women protested incredulously about their limited access to food supplies by hitting empty saucepans. When violence ensued, Allende called a state of emergency and a weeklong curfew in Santiago. He could not deny that Castro’s presence in Chile had fueled counterrevolutionary hostility. As he told his friend, the Chilean journalist Augusto Olivares, it was only “logical” because Castro’s visit had “[revitalized] the Latin American revolutionary process.”

163

Even if it was “logical,” the Cuban leader increasingly concluded that the UP had not adequately mobilized its supporters to push that process forward. In conversation with Czechoslovakia’s ambassador in Havana after his Chilean visit, he described his lengthy meetings with students and the working class as something Chile’s left-wing parties should have been doing more of on their own. And toward the end of his stay, he gave up earlier moderation and circumspection, took on a more instructive tone, and issued stern warnings to the Left about the future. Would “fascist elements” stand back and allow revolutionary progress? Castro asked. In his view, the answer was no, and he implored the Chileans to be prepared.

164

This did not mean that he supported the MIR’s increasingly public criticism of the UP and the pace of its reforms. To the contrary, during his stay in Chile, he convened an important meeting with the MIR’s leaders in which he urged the party to cooperate more effectively with Allende’s

government. As Armando Hart, a member of the Cuban Party’s Politburo who was present at this meeting, later recounted, Fidel very clearly told the MIR’s leader, Miguel Enríquez, that the revolution in Chile “would be made either by Allende or by no one” and that the MIR therefore had to unite behind him.

165

At the same time, Castro covertly urged parties within the Unidad Popular to equip themselves to fight against any future counterrevolutionary attack. During a meeting at the Cuban Embassy with leaders of the Communist Party—a party that had been traditionally skeptical and opposed to armed struggle in Chile—Castro showcased and explained the merits of various different armaments that the Cubans could acquire for the PCCh. Tell us what you need, and we will get it for you, was the message that he delivered as he showed off the weapons that were available, with Cuba’s senior general, Arnaldo Ochoa, sitting by his side. When the secretary-general of the party, Luis Corvalán, responded cautiously and conservatively about a few of the arms that the PCCh might be interested in acquiring, rumor has it that Ochoa threw his chair back and stormed out of the meeting, furious that the Chilean Communists had failed to grasp the importance and scale of what was needed.

166

Reports also reached the CIA that Castro had gone as far as privately urging UP leaders to meet the opposition’s violence with revolutionary violence (within universities and against the women’s marches). According to this source, Castro insisted that “confrontation” was “the true road of revolution” and told UP leaders not to worry about possible injuries or deaths.

167

Whether he specifically offered this advice, Fidel’s encounter with the PCCh and public speeches increasingly conveyed a similar message. He repeatedly reminded crowds of nineteenth-century Chilean nationalists who had pledged to “live with honor or die with glory.”

168

While the Chileans argued their country’s unique situation allowed them to embark on a new route to socialism without armed struggle, he insisted they could not avoid historical laws.

169

Instead, emphasizing the importance of unity with heartfelt urgency, Castro instructed Chileans to “arm the spirit” and unite behind Allende.

170

Moreover, Castro appeared throughout to be saying that as a result of Cuba’s experiences, he knew how to play by the rules of revolution in Chile better than the Chileans he spoke to. As he put it, Cuba had survived mud “higher than the Andes” being thrown at it.

171

And in contrast to the vulnerable Chileans, Castro explained that Cubans were safe from intervention because “imperialists” knew and respected the fact

that “men and women are willing to fight until the last drop of blood.”

172

Certainly, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, he recalled, Cubans had “all decided to die if necessary, rather than return to being slaves.”

173

While the Chileans were still absorbing Castro’s advice, the Cubans began preparing

themselves

for the Chilean battle they saw on the horizon. One night, toward the end of his stay, Castro went to Cuba’s embassy in Santiago despite the curfew. There, he spoke about his concerns until dawn with Cuban personnel congregated in a darkened patio.

174

Surveying the embassy at 2:00

A.M.,

Fidel Castro was appalled by the building’s defensive capabilities. “I could take this embassy alone in two hours!” he exclaimed. He therefore instructed the embassy to make sure it could withstand a direct attack, and during a secret visit the following year, Piñeiro oversaw planning toward this end. Henceforth, Cuban diplomats undertook construction work to make space for medical facilities and provisions so the embassy could survive a battle. Indeed, Cuba’s cultural attaché, commercial attaché, and the latter’s wife remember arriving at work in the morning dressed in diplomatic clothing and then changing into “work clothes.” They would then spend days or nights digging beneath the embassy to create a sizable cellar.

175

Meanwhile, the day Castro left Chile he told a group of journalists that he departed more of a “revolutionary” than when he had arrived on account of what he had seen.

176

Was Castro “disappointed” with the UP government, as the CIA concluded?

177

Looking back on events over thirty years later, Luis Fernández Oña disputed this assessment, arguing instead that Castro was “preoccupied” rather than disappointed. As he put it, “Anyone who has ever traveled to see a friend and discovered he was sick would return worried about that friend’s health.”

178

In private, Castro’s comments to socialist bloc leaders were nonetheless rather critical. “Allende lacked decisiveness,” the Czechoslovakian ambassador in Havana reported him as saying.

179

Fidel Castro also summed up his own views in a private letter to Allende that offered both praise and a pointed call for the Chilean president to take up a more combative position. “I can appreciate the magnificent state of mind, serenity and courage with which you are determined to confront the challenges ahead,” he wrote.

That is of the essence in any revolutionary process, particularly one undertaken in the highly complex and difficult conditions of a country like Chile. I took away with me a very strong impression of

the moral, cultural and human virtues of the Chilean people and of its notable patriotic and revolutionary sentiment. You have the singular privilege of being its guide at this decisive point in the history of Chile and America, the culmination of an entire life devoted to the struggle, as you said at the stadium, devoted to the cause of the revolution and socialism. There are no obstacles that cannot be surmounted. Someone once said that, in a revolution, one moves forward “with audacity, audacity and more audacity.” I am convinced of the profound truth of that axiom.

180