Amanda Adams (14 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

All this effort was driven by archaeology. Bell was passionate about it. A visit to Petra in

1900

introduced her to the grandeur of history. Located in Jordan, the “rose-red city half as old as time” was carved entirely out stone. Its beauty caught hold of her:

. . .we rode on and soon got into the entrance of the defile which leads to Petra . . . oleanders grew along the stream and here and there a sheaf of ivy hung down over the red rock. We went on in ecstasies until suddenly between the narrow opening of the rocks, we saw the most beautiful sight I have ever seen. Imagine a temple cut out of the solid rock, the charming facade supported on great Corinthian columns standing clear, soaring upwards to the very top of the cliff in the most exquisite proportions and carved with groups of figures almost as fresh as when the chisel left them, all this in the rose red rock, with the sun just touching it and making it look almost transparent . . . It is like a fairy tale city, all pink and wonderful.

17

This was the city of later Indiana Jones fame (the backdrop to

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

), and today Petra is a popular tourist destination and designated

UNESCO

World Heritage Site. But in Bell’s day it was empty—quiet and, for those who ventured so far to see it, all theirs to enjoy. After falling in love with Petra, Bell always “wished to look upon the ruins.” Between 1905 and 1914 her work and desert travel were structured, even dominated, by archaeological study. She carefully recorded the ancient sites and remnants of buildings scattered throughout the Middle East, and she was often the first European, man or woman, to see an ancient site and to announce its existence to scholars back home. In archaeology, all her talents found a unique point of intersection. Her study of history at Oxford, all the languages she spoke (including myriad dialects of Arabic), and her high taste for adventure all merged into a single, passionate pursuit. For the rest of her life, archaeology would remain her biggest joy. As she once said, “I always feel most well when I am doing archaeology.”

18

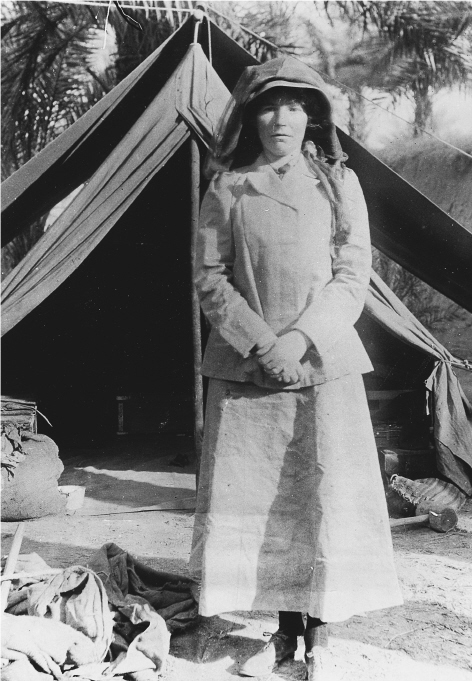

ABOVE :

Unlike Jane Dieulafoy, Bell never preferred to wear trousers in the field

AMELIA EDWARDS TOOK

a life-changing trip, the Dieulafoys tackled the world together, and Zelia Nuttall eventually settled in her favorite place, becoming deeply enmeshed in its culture and history. Gertrude Bell simply rode and rode and rode. Bell’s life was more about the journey than about getting there, and she grew to be as nomadic as the Bedouins who shared fire and food with her.

The maps Bell made as she traveled uncharted deserts became lifelines for those who would later follow in her footsteps. In addition, she had two great and lasting credits: the first was her work in the field, and the second her role in establishing the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad, where she also wrote the country’s first antiquity laws.

Bell carried an early Kodak camera on her travels and took nearly seven thousand photographs between

1900

and

1918

. Most of them feature archaeological ruins and desert tribes.

19

To this day, these black and white images are consulted for their accuracy and rare glimpse into a time untouched by Western influence. As a field archaeologist, Bell’s most significant contribution was this incredible visual record of archaeological sites, inscriptions, cultural landscapes, and sundry features of architectural and artistic value.

She never participated in a true season of excavation, partly because of her love of independence and partly because she was never invited to join a team. Single women were simply not included in respectable field crews in the Middle East at that time.

Nevertheless, no one could deny her knowledge of archaeology, and she also helped to finance some projects, earning her a bit of an “in.” It is most accurate to say that Bell focused her efforts on archaeological

expeditions

—visits to survey, map, and record sites—rather than archaeological

excavations,

where she would have unpacked and stayed put to dig in.

ABOVE :

Bell’s field tent pitched in the shadow of ancient ruins

In

1905

, at the age of thirty-seven, Bell romped through Syria in a state of bliss, visiting with the Druze people and writing of her adventures in

The Desert and the Sown,

a book so well loved that it is still in print today. Like Bell’s own field journeys, this book invited the reader to gaze upon those ruins with her, illustrated as it is with scattered photographs of statues and sphinxes, ornate column fragments, and pots. The same year

The Desert

and the Sown

was published,

1907

, Bell also authored a series of important articles in the journal

Revue Archéologique

about her findings during an excursion from northern Syria through Turkey, where she examined early Byzantine architecture. She was becoming increasingly prolific in her archaeological writing.

In the field, Bell’s greatest distinction came from her work at a site called Binbir Kilise in south-central Turkey. Her archaeological investigations at this site and surrounding areas included “churches, chapels, monasteries, mausoleums, and fortresses that had never been previously described or mapped.”

20

She collaborated with William Ramsay on this project, and in

1909

they published a book on their findings called

The Thousand

and One Churches.

Although Bell had contributed

460

pages and Ramsay

80

, the book still listed Ramsay as the primary author.

Bell’s love of archaeology took her to Greece, Paris, Rome, and beyond, as well as through the deserts of the Orient and eventually to Mesopotamia, the future home of Iraq. Through it all she was attuned to the archaeological essence of the landscape, to its potential for containing lost histories, and was distressed when corn was planted on tells because the harvested roots might disturb the stratigraphy. She was also becoming ever more attuned to archaeological nuance. A scattering of stones that might represent an old wall, a shift in soil color that might signify disturbance to an area, a hill-like mound that might contain a buried fortress—Bell was on the lookout. Her appetite for archaeological discovery was never sated. Even at dinner parties her archaeological prowess would spill forth like the amply poured wine. She would speak of this or that new site, a fresh argument made in an excavation report, or delight in new theories explaining how the first people crossed over to North America via the Bering Strait leaving a trail of stone tools and bison bones behind them.

In

1917

she arrived in Baghdad, and it was here that her life took a new course, culminating in a line of work she found vital, essential, absolutely critical: the creation of an autonomous Arab state. Her knowledge of Arabic language, desert tribes, factions, leaders, and geography was of strategic importance to the British military, and she was invited to work in Baghdad for the Arab Bureau—the only woman in a cabinet of men. The High Commissioner of Iraq, Sir Percy Cox, appointed her Oriental Secretary.

In Baghdad it was so hot that “the days melt[ed] like snow in the sun.” She bought her first house, filled it with potted jasmine and mimosa, with woven carpets and pet dogs, and got comfortable, but she soon began to run bad fevers and write letters home in which she tried her cheerful best to shrug off any concern for her latest cold or flu. Outdoor temperatures reached

120

degrees Fahrenheit every day, cooling only slightly just before dawn broke. She went from lean to thin, from inexhaustible in the saddle to fatigued at her desk, and though she clearly found her work in Baghdad thrilling and momentously important, the gaiety of her field days was replaced by a slightly stressed tone. Vita Sackville-West visited Bell in

1926

and wrote:

I had known her first in Constantinople, where she had arrived straight out of the desert, with all the evening dresses and cutlery and napery that she insisted on taking with her on her wanderings; and then in England; but here she was in her right place, in Iraq . . .

She had the gift of making everyone feel suddenly eager; of making you feel that life was full and rich and exciting. I found myself laughing for the first time in ten days . . . [She was] pouring out information: the state of Iraq, the excavations at Ur, the need for a decent museum, what new books had come out? what was happening in England? The doctors had told her she ought not to go through another summer in Bagdad, but what should she do in England, eating out her heart for Iraq? . . . but I couldn’t say she looked ill, could I? I could, and did. She laughed and brushed that aside.

21

It was an apt portrait of the nonstop Bell, hugely busy with work, engaged, chatty, and curious. At the time of Sackville-West’s visit, Bell was involved in strategic decision making to lay the foundations for a new nation and its government, and her work was fueled not only by a rarefied understanding of Arab culture but by a genuine appreciation of that culture and its people. In keeping with the prevailing views of the day, however, Bell was an advocate of indirect British rule, and she subscribed to the tenets of colonialism, viewing the world through an imperial lens, a world perceived to be in need of Britain’s civilizing assistance when in fact it wasn’t. She was a product of her time, and just as she could refer to the people of Jabal el-Druze as great friends, she could simultaneously liken the Arab population to an “unruly child” in need of obedience training.

She worked tirelessly to see that Amir Faisal was installed as king of Iraq, and in

1921

he was. While in tenure, Bell wrote strategic reports and white papers so clever that people questioned whether a woman could really have done it. In a letter to her father she explained that “the general line taken by the Press seems to be that it’s most remarkable that a dog should be able to stand up on its hind legs at all—i.e., a female write a white paper. I hope they’ll drop that source of wonder and pay attention to the report itself . . .”

22

During her time in Iraq, Bell founded the Iraq National Museum and was appointed Director of Antiquities and Chief Curator. In the latter role, her abilities matured from choosing to exhibit certain artifacts “wildly according to prettiness” to selecting materials based more on their archaeological and scholarly value.

23

Her commitment to Iraqi archaeology was firm, and with the power given to her as well as her own initiative, she collected, catalogued, and installed a vital collection for the new museum she loved and referred to fondly as her own. In the early

1920

s she also helped to orchestrate major archaeological excavations at several Iraqi sites. British and American universities conducted these investigations, and their findings bolstered the prestige of the museum where “such wonderful things are to be seen.” Scholarly recognition of Iraq, ancient Mesopotamia, increased, and the very cradle of human civilization was now seen as the source of some serious archaeology.

For all of her archaeological accomplishments, both in the field and in the museum, it was her visionary idea for the Law of Antiquities that set the greatest precedent and served not just the new Iraqi government but archaeology in general. Like Amelia Edwards, Bell was disturbed by the loss and destruction of archaeological treasures. Enacted in

1924

, this law prohibited digging up archaeological sites on private land or anywhere else without an authorized permit. In short, it put an end to unchecked looting and plundering. It also stipulated that the results from an excavation be published so that all scholars would benefit from the discoveries and subsequent advances in understanding the region’s history could be made.

The law was a progressive one, and it met Bell’s own needs as Museum Director of Antiquities and Chief Curator too: archaeologists from overseas could no longer dig a site and take the prized artifacts back home with them. The gold would stay put, as would the best of the sculptures and friezes. The best finds would be installed at the museum. It was one of the first promises to a country that it would have the right to preserve its own heritage, within its own borders and for its own people. Bell had provided the people of Iraq with a protective measure to legally safeguard their history from greed and future threats.

24

As the archaeologist Max Mallowan (husband of Agatha Christie) noted, “No tigress could have safeguarded Iraq’s rights better.”

25