Amanda Adams (17 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

The famous archaeological site of Gournia had been found. The preservation of everyday life was so great that the site was nicknamed “Minoan Pompeii.” It was a goldmine, not so much in wealth and treasure as in valuable information. Here was a full settlement where the daily lives of people who farmed and fished, made shoes, wove blankets, made pottery, hammered bronze, carved stone, and looked out to the sea for trade boats and news, could be uncovered and understood. It was a new and critical link in the chronology of Mediterranean archaeology. As the site’s significance became increasingly clear, Boyd Hawes rushed to send a telegram to the American Exploration Society. It read: “Discovered Gournia—Mycenaean site, street, houses, pottery, bronzes, stone jars.”

18

This was the Eureka moment, her dreams come true.

Gournia eventually encompassed a full three seasons of excavation (

1901

,

1903

, and

1904

).

19

Each year Boyd Hawes returned to Crete with her crew of one hundred or more men—and nearly a dozen young girls who helped to wash the potsherds—she worked to piece the architecture and artifacts of the ancient town into a semblance of understanding. She directed the men from morning until night; handled the complicated logistics of digging, mapping, and recording; and oversaw matters such as payroll and means of dissuading the workers from looting. She had reason to be concerned that when her watchful eye was elsewhere, they might pocket and sell off unique finds for a high price. All in all it was a massive effort, one that Boyd Hawes adored while living with her friend Blanche in two rooms near the site, tucked up “over a storehouse at the coastguard station of Pachyammos, which they shared with a colony of rats.”

20

Rats didn’t matter when you each day were uncovering treasures underfoot.

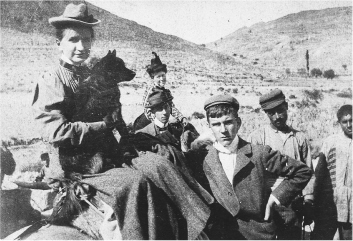

ABOVE :

Hawes in the field in Crete with her assistants and dog

Boyd Hawes operated on the same principle as Flinders Petrie, whom she visited later in Egypt and who had been so steadfastly supported by Amelia Edwards. Like Petrie, who recognized worth not just in the golden trophy finds but also in the nuts and bolts of more humble sites, Boyd Hawes operated on the principle that history is made by small acts. Yes, the palaces and thrones of antiquity are mighty and beautiful, but the little decorations on potsherds and their changes over time can illuminate the style of a whole society, from rich to poor. The presence or absence of certain types of stone or fishhook styles and the influence of architecture can reveal much more about old trade networks and spheres of influence than a single cache of ruby jewels ever could. In Boyd Hawes’s own words, “As of most subjects which deserve any investigation, the more we know the more we want to know. Palaces and tombs are not sufficient; we want also the homes of the people, for without an insight into the life of ‘the many’ we can not rightly judge the civilization of any period.”

21

Boyd Hawes embodied archaeology’s turn away from treasure seeking and toward data gathering.

With her finds stacking high, Boyd Hawes was all the more remarkable as an archaeologist because she did two things: first, published her discoveries in timely and thorough fashion, and second, became the first woman invited to lecture for the Archaeological Institute of America. This was major. It announced her stature as a true scientist in a field of men. Her talks were not in the engaging and popular style of Amelia Edwards; they were sharp and technical. Likewise, Boyd Hawes’s story of archaeology wasn’t told through a lens of emotion. It was more a tale of perseverance and character. The

Philadelphia Public Ledger

of March

5

,

1902

, reported on Boyd’s success at Gournia:

A woman has shattered another tradition and successfully entered unaided a field hitherto occupied almost exclusively by men, namely archaeological exploration . . . The results of Miss Boyd’s work must be considered remarkable, not only because of their character, but because she achieved them alone. Other women have made names in the fields of archaeological research, but these have done so in company with their husbands, who shared glory with them. But Miss Boyd’s work is entirely her own.

22

In a similar vein, Mrs. Stevenson commented: “So few women have achieved distinction as field archaeologists that Miss Boyd’s success must be greeted with peculiar pride by Americans . . . it was reserved to an American woman to undertake singlehandedly the business responsibility and scientific conduct of an expedition.”

23

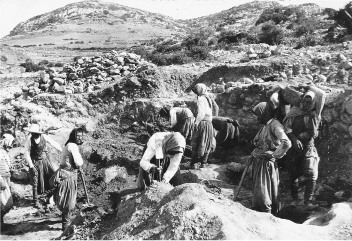

ABOVE :

The field crew at Gournia, including Boyd Hawes and Blanche Wheeler (second row from the front, first and second from the right)

They missed mention of Zelia Nuttall, but she was so rooted in Mexico, and her childhood such a patchwork of European cities, that her American story was diluted. Boyd Hawes’s work energized U.S. patriotism. And while not altogether accurate to say an American was the first woman to conduct an archaeological expedition—Gertrude Bell, a Brit, did that by herself too—Boyd Hawes was the first to lead a full-scale excavation alone, without an archaeologist spouse by her side or a team of other trained archaeologists. Her position as a true pioneer in the field was applauded. The accolades kept coming. Her publications were highly regarded. Would she remain a bright and historic star in the canons of archaeological history and its scholars, or not?

Throughout her excavations at Gournia, Boyd Hawes brought in assistants and provided them with some of the best in field excavation training. Two of those colleagues were Richard Berry Seager and Edith Hall, another Smith graduate who would soon make a name for herself in archaeology. Some later publications would, outrageously, credit the young man Seager with the discovery and excavation of Gournia. Others would describe the work as a joint collaboration between Boyd Hawes and Seager. With the passage of time, Boyd Hawes’s breakthrough accomplishments were clouded, erased in places, and slighted. She would one day reflect on “having learned how easily women’s acts are ascribed to men or completely wiped out.”

24

Boyd Hawes didn’t hesitate to point out the facts very, very clearly. She had found the buried city. The excavation permit was in her name. Gournia was, as archaeology sites go, all hers.

ABOVE :

Diggers at Gournia, where a tremendous number of artifacts and archaeological features were uncovered

“HUNT DEAD CITIES AND FIND

LOVE.”

25

That’s what one of the newspaper headlines shouted when Boyd Hawes announced her engagement to British anthropologist Charles Henry Hawes in

1905

. He had come to visit Gournia while touring the region to measure people’s heads in hopes of determining the origins of races. Harriet and Henry’s first meeting on site was uneventful (she gave him a quick tour), but later they found each other again on a boat headed to Greece. Their daughter notes that though this meeting was a crucial turning point, “they did not speak of marriage, except the ‘captive’ variety, and then strictly in anthropological terms.”

26

Boyd Hawes was thirty-four years old, and Henry wanted to marry her. She liked him too.

They wed in a small ceremony at an Episcopal church on March 3, 1906. Nine months later, Alexander Boyd was born, and four years after that daughter Mary (future author of her mother’s biography) joined the family. Out of the dusty field, Boyd Hawes was now very much in the kitchen. She had two young children to look after, a husband, meals to make, a house to tend—and a massive publication on her archaeological excavations at Gournia to complete and publish. She pulled this off before Alex could walk, but it was taxing and she had to adjust to juggling her professional passions with the domestic duties she had signed on for. Her daughter would note that “the role of housewife was totally out of character for Harriet” and that “stories of her domestic efforts became legendary.” She forgot her babies in their carriages while she shopped, cooked ambitious menus with unfortunate results, and found housework to be almost offensive, not because a person shouldn’t be clean and make their home a pleasant place, but because men were not asked or expected to do the same. Boyd Hawes had skillfully dealt with large-scale wartime nursing efforts and complex cultural stratigraphy, but a “domestic goddess” she was not.

In spite of the trials (and surely the triumphs too) that Boyd Hawes faced in this next chapter of her life, she reminds us that

she

made the choices for herself; society did not. At the age of thirty-five, she had already passed the normal marrying age; between 1900 and 1910 the average age of the American bride was just shy of twenty-two.

27

A nonconformist, Boyd Hawes had a successful career and the means to support herself. Her marriage to Henry didn’t provide materials comforts, as he was a struggling anthropologist and university lecturer who had much to offer by way of intellectual stimulation but much less in the way of financial support. They struggled to make ends meet. Boyd Hawes had married for love and because she wanted a family. She believed that women’s work should be viewed not as duty or humdrum routine, but as art. It was, as she called it, “the art of living,” and even when dinner was burning black, she became an active advocate for the worth of a woman’s work in all its variations.

28

YEARS LATER, IN

1925

,

BOYD

HAWES

meditated more deeply on the choice women face between career and motherhood. If “choice” is not quite the word—at least for the majority of women at the turn of the twentieth century—then it could be simply called the shared predicament. Can a woman be a pioneer—a convention-crushing rebel who succeeds in a man’s world against all odds—and still sing lullabies to her children at night? The question is as old as an archaeological site.

Boyd Hawes summarized her thoughts about this question: “A woman should expect her intellectual life to be interrupted, i.e., she should prepare to give the first

10

years after marriage . . . to her family interests . . . Perhaps she can keep alive her intellectual interests and return to them with new zest and judgment after the ten years.”

29

Perhaps? It’s as though a sigh escapes between the lines. After her marriage, Boyd Hawes’s fieldwork in Greece did stop, though she continued to publish. She and Henry co-authored a famous little book called

Crete the Forerunner of Greece;

it received rave reviews and was heralded as “a milestone in the progress of popular acquaintance with results of archaeological research.”

30

So while her intellectual interests persisted and found an outlet through the pen, she relinquished her days of digging. One has to wonder how much she missed them.

Forever a volcano, Boyd Hawes eventually threw herself into social issues and politics with the same gusto she had brought to archaeology. She nursed overseas again, leaving her children in the care of a nanny when necessary. And she became more and more devoted to cause of justice and international peace. She never lost her burning urgency to act, and although archaeology was a major chapter, it was truly just one of the many remarkable chapters that made up the story of her life.