Amanda Adams (24 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

Gertrude Bell was forty-four years old when she started flirting with the (married) man she loved. She was forty-five when she rode solo on a “desperate and heroic” journey through Syrian deserts.

1

She never packed her first bags looking for archaeology per se, but it later became a passion and a search that defined and shaped the route of her journeys. It was on the eve of her fiftieth birthday that she bought her first house in Baghdad and finally settled into a career she liked (and one immensely suited to her). Looked at a certain way, Bell’s life, for all its epic accomplishments, was a vagabond’s existence. She was the girl who figures out what she wants only after trying everything else first.

Harriet Boyd Hawes’s career path resembles a trajectory more common to today than a hundred years ago. She attended college and then graduate school, achieved success as a field archaeologist with her work at Gournia, and at age thirty-four married and started a family. Although this last step seems normal by contemporary standards, back then her delay to wed and breed was the exception. After the babies were born, she left them behind for a spell when called back to nurse on the frontlines of war—another unusual decision for that time.

Then there is Agatha Christie, who claimed that her life didn’t really begin until age forty. It was after she and her first husband had divorced and she was en route to the site of Ur, via the Orient Express, that she saw a major transition not just in occupation but in geography, as she and second husband Max spent much of their time living on Middle Eastern sites. For Christie, archaeology was a late-life encounter. She never saw it coming, and when it suddenly appeared before her, she embraced it (and Max) fully, sticking with the field for another thirty years.

Dorothy Garrod’s relationship with archaeology did start when she was a young woman, a student crawling through the painted caves with the Abbé Breuil. Yet at age

sixty,

just when most professors would be considering a comfortable retirement, Garrod was back out in the field with more fire than ever, excavating on the coasts of Lebanon and Syria. She had started a whole new, post-Cambridge, chapter in her life.

Although there is nothing surprising about women accomplishing great things as they mature, it is refreshing to discover women who were not only ground-breaking scientists but also unafraid and willing to change course midstream. In our youth-obsessed culture, it is wonderful to see that life really can begin at forty, and that one’s best and most satisfying adventures may be yet to come.

What is it, then, about archaeology that inspired these women to make it their life’s work, to decide it was that chance worth taking? Does the field attract a certain type of personality? T.S. Eliot once called archaeology the “reassuring science.” It was the endeavor that made Gertrude Bell feel “most well,” the mystery Agatha Christie was hooked by, the “beloved science” that Zelia Nuttall felt moved to advance. Its allure is timeless. The power of archaeology lies in its rare alchemy: the blend of history, discovery, travel, and adventure. What lies buried underfoot is its own kind of frontier: secrets of the past remain as mysterious to us as the moon.

Archaeology is an engagement with questions about what makes us human, what events and which tools brought us here today, how our ancestors saw the world, and what we can learn not just about the past but also from it. Passions run high for hidden history. They always have. Its study reveals not just the foundations and story blocks of humanness but also all of the strange, amazing, and unbelievable things our species has done, like rip beating hearts from each other’s chests, build thousands of life-size clay soldiers to protect a dead emperor, paint gorgeous creatures on cave walls, figure out how to cultivate plants to farm, and worship a universe full of complex deities through art and objects and little effigies made of bone, stone, and metal. We’ve built golden shrines and constructed temples and churches that take our breath away with their beauty. Humans have created innumerable mysteries for other humans to unravel.

Each mystery offers up potential for new understandings of who we are, of what happened and why. Did this civilization topple that one? Why do some cultures and even some species, like the Neanderthal, disappear? Which trade networks were in place, and how exactly did turquoise stones move through the southwestern United States and out to the shores of the Pacific? Why? As any archaeologist might wonder with a scratch of the head, gazing out at a partially excavated site where the walls and the artifacts and footprints of ancient houses haven’t yet made full sense—what does it all mean? Archaeology is that incredible job where you get to ask huge questions. And, for each answer you find, a dozen new questions open up. It’s juicy work.

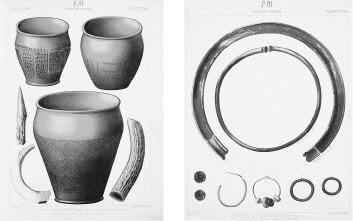

LEFT:

Decorated pottery and antler bone

RIGHT:

Metal necklace fragments, bead earrings, and pendants

Archaeology is also the very beautiful process of excavation and artifact analysis: the artisan’s process of rinsing dirt from clay beads, blowing gritty sand from gold, reconstructing the broken pieces of a finely painted porcelain pot. The material culture is innately poetic. The tools for excavation are seductive in their own right: a favorite steel trowel, rumpled leather gloves, compass, Agatha Christie’s cold cream and knitting needle.

For these Victorian-era women attracted to the field, archaeology was a means to escape the humdrum of society life, where women passed their days focused on home and hearth and were viewed as feeble little things in need of a man to watch over them. A time when feminine weakness was desirable, pale skin and fainting spells were kind of sexy. By extreme contrast, archaeology was worldly—outdoorsy. It was a line of work that kept one healthy in both body and spirit, suntanned and muscular. The first women archaeologists were drawn to a new science that afforded them the opportunity for intense intellectual stimulation— to entertain some of the questions described above—but also as a means to cleverly buck the establishment.

I don’t believe any of the ladies chose archaeology because it would prove a woman’s worth; none of them were steadfast champions of women’s rights, though some may have been feminists. Their reasons for going into the field were their own. Edwards had wanderlust. Jane Dieulafoy loved Marcel. Nuttall wanted to work in Mexico and cared deeply for indigenous culture and history. Bell was passionate for ruins and desert drama. Boyd Hawes wanted to study in Greece, while Christie was feeling brave and found the unexpected. Garrod had a family reputation to live up to. These were their private love affairs.

They were also dedicated to science, not social change. Nevertheless, as a result of their actions, academic circles, professional organizations, and even newspapers were acknowledging that female scientists were reaching new milestones. Women could endure the hardships of camping, digging, traveling; they could mastermind surveys, excavations, and field crews; they could gather the evidence together, publish, and contribute meaningfully to a science that had long denied them the chance to speak. By their own accord and strength, they kicked down shut doors. The Victorian stereotype of a weak woman was overturned. The first women archaeologists gave the women’s rights movement ammunition to demonstrate equality between the sexes.

Perhaps a certain type of personality is attracted to archaeology— an adventurous one to be sure. A little headstrong. Passionate and willing to take some risks. For just as people surely discouraged the seven women whose stories are told here, for every new undergraduate majoring in archaeology today, someone will ask, “But is there a career in that? Any money? Are you sure?” Archaeology has never been work for the faint of heart. It takes some daring. Its reward is the process (never the treasure alone): the experience of excavation and the little things you find along the way.

As Bell said, it simply feels good to do archaeology. As an archaeologist myself who has worked on digs in the Middle East and Europe and across North America, I can say that there is a delicious feeling in abandoning ordinary codes of dress and behavior and basic expectations like looking nice, being fashionable, feeling pretty. It can be delightful to work a pickaxe until you’ve got biceps like tough little lemons and hair so dirty it stays in a bun

sans

clip. Archaeology is a bit like camping with a sense of great underlying purpose and productivity; we are gathered here to uncover the past. Imagine what it was like in Victorian days to shrug off corsets and high-neck dresses. To ditch tea parties for the open road.

The story of archaeology’s pioneering women captures a critical moment in time when a group of women challenged the mode of thinking that confined them. They embody a burst of daring and freedom, as much as they do the birth of a new science.

Beginning with Amelia Edwards’s sentimental prose about the ruins of Egypt and ending in Dorothy Garrod’s concise scientific explanations and chronologies of human evolution, the seven women here represent the arc of archaeology’s own history: from romantic to pragmatic, from story to science.

Their legacy also stikes personal chords, even today. Something in the way they’d kick their donkeys to a trot, dig deeper in the saddle, board the creaky dinghy with gusto, carry a rifle, and swing the pickaxe until their strength wore out. The first women archaeologists remind us that the world is full of opportunity for the brave. They remind us that the world is big—big and wonderful.

CHRONOLOGY

: A sequence, and some would say a science, of arranging time. When archaeologists establish a “chronology” it means that they have put historical events into order and assigned approximate dates to certain styles of pottery, tools, etc.

CODEX

: Precursor to the modern-day book. The word “codex” usually refers to European manuscripts with pages all bound on one side. Codices that survive from pre-Conquest Mexico, however, are like picture books set on screenfolds. They open up like an accordion. These ancient Mexican codices contain images that are “read” as a sequence. Stretched out, they resemble ornate murals.

DAHABEEYAH

: Means the “golden boat” in Arabic. These houseboats were very popular in Egypt’s Victorian heyday. An Englishman by the name of Thomas Cook championed the vessels as the premier way for Western tourists to experience the sites of the Nile. Upper-class Egyptians also liked the luxurious form of transportation. In

1869

, the steamship was introduced to the Nile and dahabeeyahs fell out of use.

DIG

: More than a verb. A “dig” is shorthand for a full-blown archaeological excavation. Will you be going on a dig this summer? You bet.

DIRT

: Actually

not

the same as soil. Dirt is something you wash off, the muck that makes one dirty. It can be a little loose soil under the fingernails, or plain dust, grime, and technically even poop.

FIELD

: Hardly a meadow or agricultural plot. The “field” is where people venture to conduct their “fieldwork.” This means that they are out of the library, away from a desk, and are conducting original, hands-on research of some kind often with a trowel in hand.

KNICKERS

: British underwear. Commonly used in the expression, “Well now, don’t go getting your knickers in a twist!” In Victorian days, knickers were typically

open crotch pants

that fell to just below the knee and were trimmed with ribbons, buttons, and lace.

MULETEER

: One who handles the moody, kicking beasts of burden essential for packing equipment in and out of an archaeological site.

OBJECTIVE

: As in “to be objective.” Implies that all thinking has been done without the influence of emotion and/or personal bias. To be objective is, in theory, to base any decision or conclusion on facts alone.

POTSHERD

: A broken piece of a pot. Potsherds are ubiquitous on many archaeological sites, and just because they are broken, that doesn’t mean they aren’t valuable! Sherds are collected, analyzed, sometimes glued back together, and used to help assess how old a site is and who occupied it.

RADIOCARBON

: A radioactive isotope of carbon (also known as carbon-

14

). Its existence was confirmed in the mid-

1950

s and it allows archaeologists to date any object that was once a living thing (e.g., bones or wood) up to

60

,

000

years old. The testing process is complicated, but suffice it to say it works, and it revolutionized archaeology. It allowed archaeologists to pursue new “absolute” dating methods versus “relative” ones.

SEASON

(archaeological): The limited period of time in which a crew of archaeologists descend upon a site with pickaxes, shovels, and spades. A season—typically a summer, though in very hot climates a winter—is often referenced as a discrete period of time; e.g., Season

I

was highly productive! Season

II

revealed a new addition to the site. Season

III

was a disaster and bad weather ruined everything. There is usually one “season” per year.