Amanda Adams (22 page)

Authors: Ladies of the Field: Early Women Archaeologists,Their Search for Adventure

Tags: #BIO022000

At the Abbé Breuil’s persuasion, Garrod took on a gigantic research project. She pulled together all the loose strands of information— the scattered site reports, artifacts stored in different museums, and partial field notes from numerous Paleolithic excavations throughout Britain—and made sense of them all by organizing the disparate bits of information, resolving discrepancies, and folding the whole package into a large, clear picture of early human development, published as

The Upper Paleolithic

in Britain.

Still considered a classic, the work helped align understandings of human evolution in Britain with what was already recorded in mainland Europe, a long-time goal of archaeologists who had longed to make connections between the two places. For her effort, Garrod was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree from Oxford in 1924, and the road to some high-profile digs was paved.

From the start, Garrod’s intellectual quest was to throw light on the Upper Paleolithic as a whole.

17

At the turn of the century, the question of human origins was cutting-edge stuff. Take into account the fact that in previous centuries artifacts found in a freshly plowed farmer’s field were believed to be supernatural, celestial, or organic. Stone tools were thought to be the by-product of thunder; ancient pottery was believed to grow naturally in the earth, bowls taking rounded shape in soft soil, narrow jugs in the walls of rodent holes.

18

There were times when no distinction could be made between fossilized seashells, sparkling crystals, and ivory carved with decorations by a human hand; they were just strange pretty things come from above. Angel craft. Solidified stardust. Now, it was these very stone tools that Dorothy was so expert in identifying. She could pick up a chert flake, date it by style alone, set it within a chronology, and draw conclusions about our human ancestry tool by tool.

Her breakthrough moment came at the site of Devil’s Tower in Gibraltar. The Abbé Breuil had advised her to look at the site, and it proved to be a career maker. The Rock of Gibraltar is a giant mass of limestone bursting up through the sea off the coast of Spain. Human bones were picked up on site as early as

1770

, and for years following, a few teeth would appear now and then, a femur, a jawbone, and eventually some more bones of a “very primitive type” seeming to belong to that “period before the age of ‘polished stone.’”

19

In

1917

, the Abbé Breuil had spotted some more bones tucked into a small cave at the foot of a steep vertical rock peak. Garrod arrived several years later and stayed to excavate for a total of seven months. It was during this time that she made the monumental discovery of a Neanderthal child, and pieced it together from well-preserved broken skull fragments. In the mid-

1920

s, the impact of this discovery was explosive. Here was new evidence for the growing tree of evolution. Sealing the deal for Garrod’s career, she matched her huge find with a perfect report—perfectly readable to other professionals, though almost impossibly dry and technical for the layperson. “Few documents of comparable importance” wrote a friend of Garrod “have been more tersely and coolly written by a beginner who has just added a chapter to history.”

20

Her careful excavations and meticulous analysis of every soil layer, bird bone, tool type, and worn tooth were intensely thorough and put her in good stead with the scientific community.

In

1997

a scholar named Pamela Jane Smith found a lost archive in the Musée des Antiquités nationales outside Paris. The rumors about the burned papers were false. In it was a lifetime of Garrod’s handwritten field notes, photo albums, and site documents. One photograph in particular gives a telling glimpse of Garrod’s work and her love for it. She named the remains of the Neanderthal child, assessed to be male, about five years old, Abel. The picture shows a thirty-four-year old Dorothy smiling, sitting above the excavation trenches, cupping the small skull in her hands. She looks really happy. In her personal album this photo was given pride of place, decorated on each corner by a little red star.

21

While Jane Dieulafoy had Susa and Harriet Boyd Hawes had Gournia, Garrod’s fieldwork extended all over the map. Because she was tracing human origins, she moved through the Old World as our ancestors might have: full of curiosity and with deliberation. During her career, field explorations took her to Palestine, Kurdistan, Anatolia, Bulgaria, France, Spain, and Lebanon. With the exception of one excavation at a French site called Glouzel that left a bitter taste in her mouth (the site was a hoax, salted with fake artifacts and highly publicized to embarrassing degree), all of her sites were major. The Abbé Breuil provides a good summary of the string of her accomplishments that drew attention to Ms. Garrod’s capacity for more distant undertakings, and was the means of her being appointed to the direction of researches in caves of the Near East, to which, in

1928

onwards, she gave all her time. “With various collaborators she explored in

1928

the cave of Shukba (

27

kilometers north of Jerusalem), and those of Zarzi and Hazar Merd in Southern Kurdistan. After that she explored the group of caves and rock-shelters of the Wady el-Mughara near Haifa . . . These last excavations were particularly lucky, admirably conducted and excellently described.”

22

Garrod’s work in the caves of the Wady el-Mughara at Mount Carmel—where she was the director of joint excavations undertaken there by the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and the American School of Prehistoric Research—lasted from

1929

to

1934

and produced some of the most important human fossils ever found—more Neanderthals and a rare, nearly complete female burial.

Garrod was responsible for designing the excavation strategies for several, sometimes simultaneous, excavation sites during seven seasons, soliciting and budgeting finances, setting up camps, choosing, hiring, training and supervising her co-workers, arranging for equipment and supplies, dealing with British Mandate officials, and maintaining cordial relationships with the local Arab employees and their community. She was notified of all finds and made the decisions on how to preserve and to catalogue the abundant archaeological remains. The analysis of artifacts required an extraordinary effort . . . Garrod was responsible for analysis of all this material, writing field reports and publication of results. She handled these formidable tasks expertly.

23

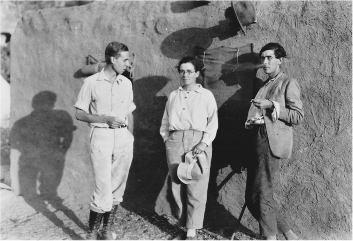

ABOVE :

Dorothy Garrod and two of her field colleagues

The archaeological remains from the Wady el-Mughara included an astonishing 87,000 stone tools alone. Garrod undertook all of the classifying and cataloging of these artifacts by herself.

24

It was a task that could have lasted a less able person a lifetime.

The results of her work eventually produced a detailed chronological understanding of the Stone Age in the Levant region, published in

The Stone Age of Mount Carmel

(

1937

). The book was a triumph, and Garrod was awarded honorary doctorates from the University of Pennsylvania, Boston College, and Oxford University. Thanks to her, the Levant had become the best understood area of human evolution in the world at the time, unmatched in its clarity of sequence. Garrod was not just a woman making advances in science but an archaeologist taking giant strides through the field, and her influence was legendary. By

1939

, she was considered one of Britain’s finest archaeologists.

WHEN WORKING IN

the field, Garrod was regularly in the company of male colleagues, students, and assistants who were all smart and commendable professionals. But more often than not, her field crews were composed exclusively of

women.

Whether it was by chance (the best qualified people all happened to be female) or outright preference (to advance a feminist agenda), it was no longer the “boys’ club” that reigned unquestioned. There was now a sort of recognized ladies’ club in the fields of archaeology, all of whom were conducting groundbreaking research.

The “ladies’ club” had existed as only a fleeting entity until Garrod formalized it. Its spirit harks back to a vignette that Margaret Murray, an archaeological predecessor of Garrod who taught hieroglyphics and excavated in Egypt in

1902

, wrote while delighting in feminine companionship on a site. There had been a suspicious noise in the camp one night, a sign that some looters might be causing trouble. Murray suggested they have a look:

ABOVE :

Garrod and her all-female excavation team at the Mount Carmel Caves, 1929

“Oh, yes, go if you like.” But Mr. Stannus was shocked at the idea of three defenceless women ‘going into danger’ without a man to protect them, so he gallantly came too. He got the shock of his life when we three women joined hands and danced with a great variety of fancy steps all the way from the camp to the dig. The joining of our hands was precautionary, for fancy steps on those tumbled sand-heaps in the uncertain light of the moon is a tricky business. Poor Mr. Stannus, he had always been accustomed to the Victorian man’s ideal of what a lady should be, a delicate fragile being who would scream at the sight of a mouse.

25

The little moonlit dance in which three women linked arms to buck the conventional view of ladylike meekness foreshadowed a larger movement. Garrod’s decision to create a work force almost entirely of women was unusual for her day, and it certainly commanded attention from the establishment. She hired local Arab women to assist on her excavations, since they worked extremely well and the money she paid them went directly to the needs of their families.

26

During her first season at Mount Carmel her excavation team was nearly all female: the Arab girls did the basic digging, and four university-educated women—Elinor Ewbank, Mary Kitson, Harriet Allyn, and Martha Hackett— assisted her. The really heavy physical work was taken on by local men.

27

Garrod’s actions gave field feminism a push, and as one of her crew, a woman named Yusra, explained: “We were extremely feminist you see because all the executive and interesting part of the dig was done by women and all the menial part . . . by men.”

28

The tables had turned.

Whether or not Garrod and her women colleagues ever danced by moonlight is their secret, but they definitely enjoyed a ritual glass of sherry. “Sabbath” sherry was at

6

:

00 PM

sharp, and even the “mud, muck, ooze upon the floor, torn tents and thunder—all were forgotten as the sherry bottle was opened.”

29

Archaeological field conditions remained as challenging as ever, and the women were exposed to heat, murderous humidity, dirty drinking water, storms, and disease. Some became quite ill. But sherry was a cheering curative, a reason to toast the hardships of the field—so rough in the moment, so good when told as stories later on.

Garrod’s camaraderie with other pioneering women archaeologists (though she was normally regarded as “the boss”) extended throughout her career. Her most enduring relationships— both as professionals and as close friends—were with two women: Germaine Henri-Martin, the daughter of an archaeologist whose site Garrod had worked on in her post-graduate days, and Suzanne de St. Mathurin. All three excavated together at different sites; all were prehistorians. Many of the excavations they conducted were in France, and as their achievements were increasingly recognized in the press and within academic circles, the French affectionately nickname them

Les Trois Grâces

(The Three Graces). The three pioneers remained together even in death—their archives at the Musée des Antiquités nationales are kept together. Each woman left the others her favorite photos and keepsakes. And so they remain bound.

Les Trois Grâces

joined together late in their careers to aid a significant site in peril, a cave called Ras el-Kelb in Lebanon. The year was

1959

, and two tunnels were being blasted through the rock; the integrity of the Paleolithic cave would be destroyed. Damage had already been done to the site years before when a railway had been laid down adjacent to it, and now the Director of Antiquities in Lebanon had requested that Garrod come out immediately and conduct a rescue dig.

Les Trois Grâces

arrived on the scene.