American Eve (27 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

If Harry was notable for anything among his barroom acquaintances, it was a “touchy bluster that stemmed from frustrated snobbery.” He was also easily bored. Of London he wrote, “The dances are tiresome. If Royalty comes, worse. You see rows and rows of girls, most tied to each chair.” This, in fact, was a sight he was all too familiar with, though in a distinctly less staid way. He had done more than just dabble in bondage and flagellation in the bordellos from Pigalle to Budapest, and Harry’s desire to handcuff or truss up women was but one variation on a sadistic theme that frequently ran through his one-note head.

No matter what the circumstances, Harry always walked quickly, with a long-legged, nervous gait, although to certain observers, “never seemed able to walk in a straight line.” This inclination had been noted by an instructor at Wooster Prep School, which Harry attended at age sixteen. The teacher described his walk as an erratic kind of “zig-zag which seemed to involuntarily mimic his brain patterns.” From there Harry went on to the University of Pittsburgh, where he barely tried his hand at law. After that, he enrolled in a special course at Harvard, where, by his own account, he “studied poker” and became a “cigarette fiend.” During his brief tenure at Harvard, where he continued to be put off by the study of law, Harry’s cigarette habit, combined with unspecified “immoral practices” and threats to fellow students and staff, got him hastily but quietly expelled.

Not only was he the product of a stern, distant father and a shamelessly suffocating mother, Harry Thaw, as it would subsequently be revealed at his murder trials, came from “tainted stock.” Since infancy Harry was a problem child, his résumé studded with the bizarre. Given to long bouts of chronic insomnia, temper tantrums, and baby talk or wild incoherent babbling, all of which lasted well into his late adolescence, Harry duly impressed specialists, family physicians, nurses, and tutors with his tenacious and abnormal refusal to leave his infancy behind him. Among the list of childhood diseases (including whooping cough, scarlatina, strep throat, and mumps), perhaps Harry’s most exotic illness was a bout of Saint Vitus’s dance, although some later suspected it might have been a mild form of epilepsy. Saint Vitus’s dance, a disorder associated with rheumatic fever, which Harry also had as a child, is characterized by jerky, uncontrollable twitching and movement of either the face or arms and legs. In the Middle Ages it was considered a sign of demonic possession, and usually lasted about a month or two (unless the afflicted died accidentally because of the fervor of an exorcist or cleric). In Harry’s case, no exorcist had ever been called, and so it seemed to linger for thirty-plus years. But Harry Kendall Thaw knew the source of his torment—the devil White.

When Harry was growing up, no one could discipline the truculent troubled child. Only his exasperated father had tried, and only infrequently. Once the elder Thaw was dead and Harry was eighteen, there was no one willing or able to strap him down. His siblings held him at arm’s length and mostly kept to themselves, watching with contrived indifference as their mother fed Harry’s insatiable narcissism. But because he was a child of wealth and privilege, his bizarre actions were tolerated as eccentric by his family and as spoiled by the staff, so that by the time Harry reached his late teens, a repertoire of puerile behavioral aberrations was firmly established as part of his inventory of adult quirks. He continued to speak baby talk (in his letters to Evelyn from prison, Harry wrote to his “Boofuls,” his “Tweetums,” and to “Herself”). At other times, he was given to “outbursts of uncurbed animal passion.” He often amused himself by throwing crockery or sharp, heavy objects at the heads of servants. He was reported to have pulled off the tablecloth and kicked his pheasant and foie gras into the fireplace on several occasions when they were not prepared as he had directed. Easily distracted, he could just as easily become fixated on an idea to the exclusion of all else. It was also reported that after a halfhearted suicide attempt while on a European tour in his early youth, having attempted to cut his own throat, Harry had been temporarily committed to a private sanatorium in England. Yet all of this he managed to keep under wraps. Or rather, Mother Thaw did.

Perhaps his mother’s consistent myopia regarding Harry’s aberrant propensities was sheer denial, knowing that several members on her side of the family had been institutionalized for insanity. Then again, perhaps there was a more tragic and harrowing psychological explanation for Mrs. Thaw’s attitude toward her son. In a letter to a friend years later, Evelyn relates a horrendous event that she learned about soon after marrying Harry—a story that would give Freud nightmares. Apparently, Mother Thaw had given birth to a baby boy a year before Harry. But one night, while sleeping in the bed with his mother, the colicky newborn was accidentally smothered to death under one of Mary Copley Thaw’s pendulous breasts. The child’s name was obliterated from family records, and Harry was produced a year later.

For Harry, mother’s milk and money were indistinguishable; Mary Copley Thaw paid for his best clothes and worst habits well into adulthood. And eventually, in spite of her best efforts, the entire world would see how far Mother Thaw would go to compensate for that horrible loss of her firstborn infant son, and try to deny the genetics of insanity when the family’s numerous skeletons were dragged out of the closet and “put on exhibit in grinning succession in open court” after Harry’s crime of passion.

JEKYLL AND HYDE

He was a zigzagging contradiction, part gentleman, part boor, part prude, part playboy (it is alleged that he was the person for whom the term as we know it was coined). He could be charming and tyrannical, sincere and pretentious, solicitous and sadistic. Unlike Evelyn, who possessed a marvelous “sensayuma” (her word, which appears in letters she wrote late in life), Harry took himself too seriously to detect even a whiff of humor in everyday things, except when it was inappropriate. Evelyn admits, however, that he did have “a kind, sweet, generous, and gentle side.” As she stated years later for those who often wondered about her own sanity in marrying him, “I could not have loved a man who didn’t have some of the finer qualities of humanity.” It was this and only this “finer” part of Harry that he was careful to show to Evelyn during the early phase of their “friendship.” Ironically, like the man on whom he was fixated, Harry Thaw also led a double life, although his closet debauchery and depravity far outdid White’s concealed life as a “notorious seeker of pleasure in strange ways.”

Posing under another assumed name, Mr. Reid, Harry played at being a theatrical coach of some sort and scoured the Tenderloin district for gullible, unsuspecting prey. Once he had paid for a room as far as possible from any others in a less than respectable hotel, Harry would then pay an additional fee to various proprietresses for the privilege of having underage, stagestruck girls come to his rooms for “tutoring.” But the unorthodox lessons Harry taught them were not what they expected. As Mr. Reid he would beat them with dog whips, handcuff them, tie them to chairs and headboards, put them in leg irons, scream in their faces and berate them, reportedly scalding at least one in a bathtub to punish her for her

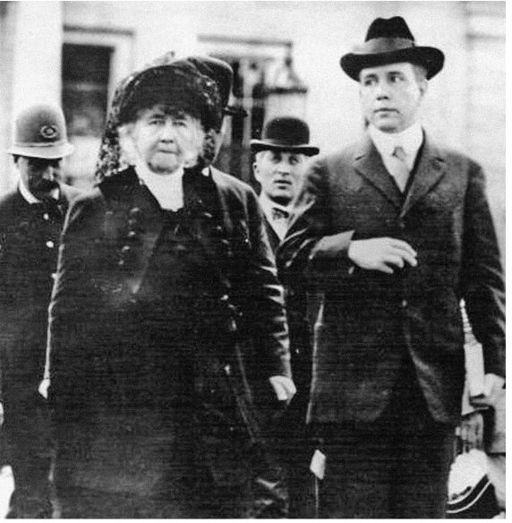

Mary Copley Thaw and her son Harry, circa 1906-1907.

immoral disposition (thus earning him the nickname “Bathtub Harry”). Before his second trial, a woman named Susie Merrill, who ran a house “all of whose guests were of questionable morals,” swore in an affidavit to these and other facts about Thaw’s “queer” proclivities, which he had whetted in the most depraved corners of the Continent (in Paris, for example, he was considered “the most perversely profligate of all the American colony there”).

Merrill described his modus operandi in her affidavit: “He advertised for girls from ages fifteen to seventeen. He had two whips, one like a riding crop, the other like a dog whip. On one occasion, I heard a young girl’s screams. Then I saw her partly undressed, neck and limbs covered with welts. I found others writhing from punishment.” Merrill estimated that Thaw had paid out about $40,000 over the course of two years to more than two hundred girls he had lured to her establishment. (Most of these facts would not come out until after the second trial, when, within weeks of offering to testify, Merrill died suddenly and mysteriously, unable to confirm her allegations under oath.)

After the evening of his unveiling, Harry would not leave Evelyn alone. He phoned her, pestered her with fervently written “mush” notes (his term), sent tokens of his esteem, did anything he could think of to earn her favor. At first all he managed to do was whip up the interest of the press, where it was reported that little Miss Nesbit “sent back two dozen pairs of the finest silk stockings and a Steinway piano delivered to her apartment, which already had one, thank you very much.” According to one stage manager, “You have no idea how that child is annoyed by the attentions of men, especially of a man named Thaw.”

Once she became fully cognizant of Thaw’s determination to purloin her precious daughter, Mrs. Nesbit not only expressed her extreme distaste for him, she took every opportunity to try to curb any interaction between Evelyn and Harry. He was an all too gross and fleshy reminder of the part of her former life in Pittsburgh she wanted to stay buried. Nor did she want to anger White. It is also possible Stanny had gotten an ill wind of this new development and told Mrs. Nesbit that Evelyn should stay away from the devious and intractable Thaw. Why else would she have discouraged a multimillionaire’s son (and an unmarried one at that) from pursuing Evelyn, not-so-past insults aside?

Nonetheless, going against her own instincts and half-cooked teenage lack of common sense, Evelyn ignored the warnings of her mother and Stanny. Not only did she stop discouraging Harry, she even grew to like him for what she characterized as his more “feminine” side. He was attentive to her needs alone, thoughtful, courteous, and sensitive. Coming immediately on the heels of the Barrymore breakup and the punishment that followed, her mother’s and Stanny’s disapproval were reason enough for Evelyn to permit her relationship with Harry to continue, even if motivated more by spite than sincere interest.

So, regardless of his more noticeable peculiarities, after almost four weeks, Evelyn formed “a genial friendship of sorts” with Harry Thaw. And at least at first, the “course of their friendship ran smoothly.” She visited his rooms at the Knickerbocker Hotel one morning, where he showed her some old laces that she liked very much. He wrote in his memoir, “Had she told me, I should have given all to her.” He wholeheartedly approved of her leaving the stage and returning to school, and told Evelyn very emphatically that the theater was no place for a nice little girl like her. Compared with Stanny’s and her mother’s, Evelyn felt that Harry’s concern for her well-being was genuine. As far as she could see, he had nothing personal to gain in supporting the turnabout of her career path. As the time of departure for Mrs. deMille’s school neared, Evelyn’s love of learning, combined with Harry’s unwavering and seemingly unselfish emotional encouragement, soon rekindled a spark she had thought permanently extinguished.

Privately, though, in spite of his vigorous endorsement of her leaving the stage, Harry couldn’t help feeling frustrated by the fact that just when his lovely golden girl was within reach, she was to be snatched away and sent off to New Jersey. The school was one of any number that White could have chosen, but he apparently had some connection to it, either through Mrs. deMille and her theatrically inclined family, or as has been suggested, through the experience of sending other girls there and finding his secrets kept safe. He was also still providing for Howard’s schooling, perhaps out of genuine affection for the boy or because of Mrs. Nesbit’s not-so-subtle endless harping about her fatherless son.

Just before she left New York, Harry came to see Evelyn and, according to her, proposed marriage. She refused, politely, and told a dejected Harry that she liked him well enough, but that her life was too complicated at the moment. Of course, what she couldn’t tell him was that she was not exactly the nice little girl he thought she was and she felt it hard to pretend otherwise. Nor could she tell him that the man he obviously despised was the one “who had spoiled her for anyone else.” So she left in October, and in January 1903, a down-but-not-out Thaw went on an extended holiday to Monte Carlo and Cannes to relieve his frustrations, drink, and gamble excessively. And plan his next move.

Although Stanny had made “laborious arrangements” so that Evelyn’s association with the theater should not be mentioned, it wasn’t long after she arrived that the information leaked out. A number of pupils had heard of the new girl and others had seen her picture, so there was no denying the fact that she had been an artist’s model and on the New York stage—a double threat. In addition, there was the intermittent and disruptive presence of reporters and photographers who sought to get an exclusive photo of Evelyn in her school uniform and on her way to classes.