American Eve (9 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

When Florence Evelyn told Beckwith one afternoon soon after she had begun posing for him that she planned to seek out additional modeling work on her own (since her mother seemed incapable of finding work but moaned incessantly about their not having enough money), the artist raised his hands in dismay.

“You are not the sort of girl,” he cautioned, wagging his finger, “that should go knocking at studio doors.”

He offered to give her some new letters of introduction to respectable artists in New York, men whom he described as “eminently safe.” As he went to a dilapidated desk to search for pencil and paper, the girl’s thoughts reached back to the Pittsburgh boardinghouse and the unsavory prospect of asking for the rent from boarders at her mother’s urging. Thanks to Beckwith’s intervention, however, the teen soon found herself posing for a number of legitimate artists, including Frederick S. Church, Herbert Morgan, and Carl Blenner, without having to knock on any strange men’s doors.

At first her workload was fairly light, and the poses Florence Evelyn was asked to hold were not particularly difficult. With her “liquid brown eyes,” “rosy Cupid’s bow mouth,” “softly rounded translucent shoulders,” “wildly abundant tresses,” and “the most perfectly modeled foot since Venus,” Evelyn’s Pre-Raphaelite looks were indeed an artist’s dream in the flesh. As she eased back into life in the studios, within a scant few months, the “girl from the provinces” began to attract enough attention to become a particular favorite of the New York artists (just as she had in Philadelphia). She was soon in demand by a significant number of painters, sculptors, and illustrators.

One day a reporter came down to the boardinghouse to interview Miss Florence Evelyn, notable as the first of what would soon become a regular routine in her life. Her mother showed him the Philadelphia photographs, one of which was promptly printed in one of the New York evening papers. When the

Sunday American

published two big pages of photographs, the short fuse of modern celebrity was ignited. Even so, at such a young age and with so little knowledge of how the world worked, the adult Evelyn would come to believe after some reflection, “I do not know that to be brought into the public eye so young is the happiest of experiences.” Nor was it something her mother was equipped to deal with, any more than she had been regarding her husband’s hopeless finances.

Being interviewed by a bona-fide New York reporter was “a novel experience that first time,” the adult Evelyn wrote in 1934, and slightly less satisfying each time after that, especially when she realized that her mother concealed from her how much money they had and how much she was paid for such frequent “exposure.” As for Mamma Nesbit, she gradually adapted to her role as “manager” of her daughter’s career, despite a complete and consistent lack of business sense and only intermittent concerns about the possible impropriety of life “in the studios” for a girl barely sixteen years old.

According to Evelyn thirty years later, when she began her career in New York City, “in the main they wanted me for my head. I never posed for the figure in the sense that I posed in the nude.” As her mother would tell reporters, “I never allowed Evelyn to pose in the altogether as did Trilby”—although there is suggestive evidence to suggest otherwise. Evelyn herself describes a painting of her, done by Frederick Church in July 1900, that was hung in the Lotos Club in New York: “[I was] an Undine with water lilies in [my] hair, running down my bare limbs, [with] two striped tigers at [my] flanks.” Another painting, done by Carroll Beckwith in 1901, shows a decidedly demure but partially nude young woman, her hair piled loosely on her head, in an open kimono with one breast exposed; the young subject stares almost straight ahead. It is titled

Miss N.

While the tactic of putting a barely clad young female model in a diaphanous classical costume, surrounding her with cherubs in some spurious mythical setting, or laying her out in an “Oriental posture,” helped both avant-garde and academic artists circumvent middle-class prudery (and sometimes avert censure), to those not interested in serious or high art, a studio model’s real or thinly veiled nudity and seductive poses were either good for cheap titillation or an abomination. Such was the case with the obvious suggestiveness of many of young Florence Evelyn’s poses, intensified by the low-cut, flimsy, or minimalist but strategically placed drapery she wore where less was significantly and scandalously more.

In a number of pictures, Florence Evelyn gives the appearance of one “just budding into girlhood,” and at times a distinctly peaches-and-cream American girlhood. Another of Beckwith’s paintings, depicting a demure and comely Evelyn in a long-sleeved, high-necked black and red velvet dress is simply titled

Girlhood.

However, despite her Irish-Scottish-English ancestry, her natural coloring—brunette hair, heavy-lidded dark eyes, alabaster skin, and full-lipped pouty mouth—struck all who saw her as strangely foreign and decidedly Oriental, a loaded word that conjured up “naughty visions” for Americans at the time. As a result, she was frequently asked to model in the garb of “an Eastern girl in Turkish costume, all vivid coloring, with ropes and bangles of jade” about her exposed neck and bare arms.

The striking exoticism in her images inspired men and women alike to make comparisons with legendary beauties of the ancient past. She was Venus, Nefertiti, and Cleopatra all rolled into one sultry and precociously erotic package that belied her years. She was, according to various reporters, Psyche, the Sybil, or “a Siren out of Homer.” Struggling to find the words to describe the hypnotic effect she had on those who saw her newest pictures in his case, one photographer hit upon it exactly—her look was “innocence and experience combined.” She exuded the egglike virginal fragility of Shakespeare’s Ophelia one moment and the brazen sensuality of wicked Salome the next. It was mere speculation on the part of observers which pose might be closer to the truth.

To most who saw her pictures and photographs, Florence Evelyn appeared at times oddly detached, her expression tantalizingly inscrutable, enough to cause more than one reporter to refer to her as “the Little Sphinx.” Her calm, unflinching gaze was, to the more reactionary, “a bold and impudent coquettish stare” that affected observers in the same way it had unnerved those who saw her when she was a young child. For most, trying to read something into the little Sphinx’s eyes was a perplexing enterprise. It was like looking at a mirage—something of the depths might appear visible but was indistinct and tantalizingly beyond reach, perhaps even illusory. The serenely enigmatic expression on her face intrigued observers, most of whom assumed it was a look she was trained to give. In reality, it was as natural to her as breathing.

As a result, in keeping with the upbeat tempo of the times, like Cinderella stepping from the pages of her storybook, the little girl from the outskirts of the sooty city rose seemingly overnight from deprivation and obscurity to become what one reporter called the “glittering girl model of Gotham.” Very quickly after that first interview, a steady stream of newsmen came around the boardinghouse, anxious to have a photograph of “Miss Florence Nesbit,” the girl destined to “flash into public view as a famous beauty.” This was also the beginning of some confusion on the part of reporters and the public. Since she was Florence Evelyn and her mother was Evelyn Florence, a number of times the names were confused, with captions that read Miss Evelyn Florence or Miss Florence Nesbit.

Broadway Magazine

published a two-page spread with the Phillips photographs, but with two different names, as if Evelyn were her own twin.

There was also continued confusion and speculation about how old she was, since her mother invariably increased Evelyn’s age by two or three years to skirt the thorny issue of child-labor laws. But as Florence Evelyn’s popularity rose, the prickly question of her age piqued the curiosity of more than one secret admirer—and sent a red flag up for the vigilance societies, particularly the one run by a bulldozing man who had been a Civil War general and who saw Manhattan as little more than “Gotham and Gomorrah.”

COMSTOCKERY

Sex. The stark impropriety of living, breathing models stripped of their previously mandated flesh-colored body stockings. The dubious avant-garde practices of the Art Students League. In fact, the entire question of what defines art as opposed to pornography (particularly if children were involved) was but one battle being waged in the explosive culture wars of the newest century, where, according to Evelyn years later, girls like herself were “sacrificed by straight-laced morality on the altar of mid-Victorian prudery.” It was a decade where the fanatically puritanical still covered piano legs so as not to expose “too much limb,” while at the same time newly coined euphemisms for a woman’s private parts proliferated, including such colorful phrases as daisy den, ivory gate, Cupid’s crown, and Bluebeard’s closet. Like the ancient serpent, the Ouroboros, with its tail in its mouth, the age-old bugaboo of sex wound itself up-, mid-, and downtown in self-propelled vicious circles—and inevitably coiled around Florence Evelyn.

When it came to sex, the “Naughty Oughts” were of course, for many, a dim and confusing time. Boys were dressed as girls when very young, and girls played boys onstage. One of the most popular productions of the day was J. M. Barrie’s

Peter Pan,

the story of the boy who never wanted to grow up and become a man—and wouldn’t when played by actress Maude Adams. The whole subject of birth control was taboo in a society where “prophylactic” meant a popular brand of toothpaste. Information, medical or otherwise, regarding sexual activity was virtually nonexistent for women (it would take another ten years for Margaret Sanger to begin her campaign to educate the public about such things, and she would face not only withering criticism but the constant threat of imprisonment). Men, meanwhile, did have contraceptives available to them in the form of sheepskin condoms, but only if they were urbane enough to be “in the know” and willing to procure them “under the counter.” Otherwise, they relied on the ancient methods of withdrawal, dumb luck, abstinence, and perhaps prayer to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

There were skirmishes unfolding on a wide variety of sexually charged fronts even as Tom (and Dick and Harry) foolery of every illegal and immoral kind appeared ready to burst through the seamy cracks that were exposing themselves in various parts of the city. But those who were routinely engaged in nocturnal missions of dissolution found themselves

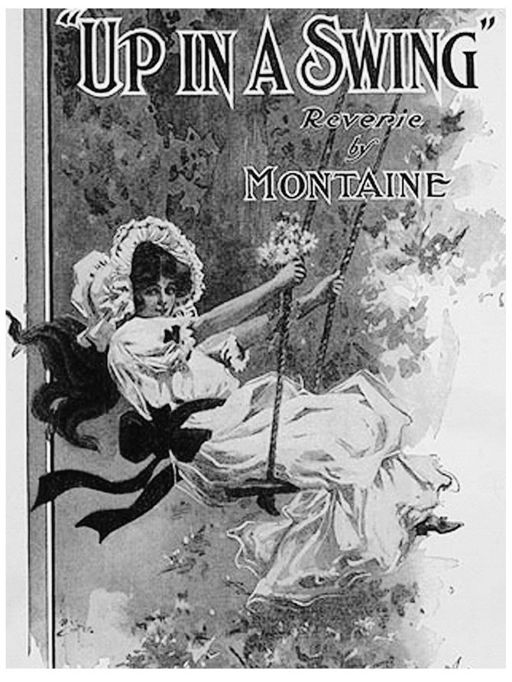

Typical image of innocent girlhood on sheet music, circa 1900.

locked in almost weekly moral combat with the one-man army named Anthony Comstock.

Defender of the innocents and crusader for purity, Comstock saw on the “alien island” of Manhattan a swarming battlefront, and the great campaign before him consisted of holding the line between what he believed was morally uplifting versus the eyebrow-raising immorality of nearly everything else, including the breezes blowing around the Flatiron building that lifted women’s skirts. Decades earlier, Comstock made a name for himself as the sponsor of what are still known today as “the Comstock laws”—anti-obscenity legislation that makes it a crime to send any materials with sexual content through the mail (particularly those offering information on birth control).

Comstock made pronouncements almost daily, condemning the New Woman (one was arrested for smoking a cigarette on Fifth Avenue), the naturalistic novels of Stephen Crane and Theodore Dreiser, the Five Points area, beer halls, ragtime music, Sandow the strongman, amusement park rides, “saucy” sheet music, lotteries, dime novels, cigarette cards, Tin Pan Alley, bicycles, and even the aristocratic sport of tennis (an “ungraceful, unwomanly and unrefined game that offended all canons of womanly dignity and delicacy”). The only actual physical entertainment for women that was exempt from Comstock’s reproach was swinging (in the literal sense, that is). He considered riding on a swing an innocent and innocuous form of exercise for young ladies, bound as they were to a male-dominated ideal of naive and girlish femininity that strove to keep them perpetually infantile.

Comstock attacked with equal force and watchfulness everything he believed offered fleshly or sinful distractions. A number of years earlier (when Teddy Roosevelt was still police commissioner), the sober-minded Comstock had tried to get the police to enforce the Sunday blue laws and close the saloons. But his success was limited and ultimately short-lived. His well-publicized campaign against all that he considered indecent came to be known as “Comstockery,” so named by the curmudgeonly Irish dramatist George Bernard Shaw, whose frank and thought-provoking naturalistic plays such as

Mrs. Warren’s Profession

and

Major Barbara

were specific targets of Comstock’s conscience-hammering censorship.

Mrs. Warren’s Profession

was closed after only one performance in New York, and several other plays suffered similar fates.