American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms (23 page)

Read American Gun: A History of the U.S. In Ten Firearms Online

Authors: Chris Kyle,William Doyle

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction

A rare sight: U.S. troops operating a Maxim machine gun. Texas, 1911.

Library of Congress

Not to be outgunned, the Germans and Russians ripped off the Maxim design for themselves. The lethal firepower of the machine gun was one of the big reasons World War I became such a bloody mess. No war is pretty, but trench warfare brought the ugliness to new lows. Military commanders on both sides were insanely slow to adapt to the new combat conditions on the ground. Hundreds of thousands of troops were mowed down in pointless assaults “over the top” as they ran into the killing fields ruled by the machine gun.

By the time the United States entered the war, there were four fairly decent machine-gun options available on the open market, all conceived by Americans: the Maxim, Lewis, Benet, and the Colt Model 1895, designed by the great John Browning. If you wanted to choose just one, the Lewis gun would have been a pretty good bet, especially since it could be set up and handled by one man, with another toting the ammo. The earliest models of the Browning had performed well in limited service in the Spanish-American War of 1898. But the usual delays and muddled thinking at the Ordnance Department meant the Americans ended up with French machine guns at first; only toward the end of the war did the Lewis and Browning weapons start coming to the troops in any numbers.

Those French machine guns? Well, a few thousand were Hotchkiss machine guns, which were manufactured by the company Benjamin Hotchkiss had established in France the previous century. Modern descendants of his “cannon-revolver,” the firm’s family of machine guns were decent, though very heavy for infantry weapons.

But most of the guns the Americans ended up with were Chauchat light machine guns. These featured magazines with exposed cartridges that jammed every time they got into mud or dirt—pretty much an everyday thing in combat. Welcome to war!

There were a few cool things about the Chauchat, like the fact that it had a pistol grip and was lightweight—the “Pig” or Squad Automatic Weapon of its day. But if you were in the trenches depending on a Chauchat to save your hide, prayer might have been a better option.

Until this point, the machine gun was a stationary weapon. It was great at defending territory and providing cover fire for an advance. Nice guns, as long as you didn’t have to move them: the best were heavy mothers. Most took two or more soldiers (and maybe even a horse) to operate, transport, and carry the ammo.

Anyone who thought about it, or busted his hump carrying one of them, knew the future of firearms lay in a fully portable, handheld machine gun. As it happened, one American figured out how to make it happen.

John Taliaferro Thompson was a rare thing: a brilliant and farsighted Army ordnance officer. A Kentucky boy, he headed north and graduated from West Point. A colonel by the time the Spanish-American War started, he did a reasonably good job as the chief ordnance officer attached to the commanding general of the Cuban campaign.

As a member of the Ordnance Department, Thompson played a key role in getting the M1903 Springfield rifle and the M1911 pistol made. He and Major Louis LaGarde supervised the torture tests that selected the winning M1911 pistol design. By 1914, he had automatic weapons on his mind. He retired from the Army and went over to Remington Arms as their chief engineer. He also started a company called Auto-Ordnance to manufacture an automatic rifle. Auto-Ordnance partnered up with a Navy man who had patented a delayed blowback breech system, and went to work adapting it to a rifle design.

The war convinced Uncle Sam that the Army needed Thompson back, and he was recalled to active duty. He was put in charge of American small arms production. But the automatic rifle was never far from his mind, and his company kept working on it.

The blowback breech system had a lot of promise, but the engineers Thompson hired discovered that using rifle cartridges caused too many problems. Bullets had a very nasty tendency of firing too soon, which can really put a dent in the day of the guy holding the gun, not to mention the people around him. Bullets that followed often didn’t eject smoothly, which wasn’t quite as bad a problem but still didn’t make for a happy operator.

The engineers did some thinking and decided what they really needed was a shorter cartridge. Thompson and his team soon turned to one he knew very well: the .45 ACP rounds that did such a good job in the M1911 pistol.

While pistol rounds simply don’t go as far as cartridges made for rifles, in the close quarters of a trench, maximum short-range stopping power trumps long-range accuracy. Since the gun was meant as a trench clearer, Thompson realized, the bullets were perfect.

Re-retired, Thompson went back to Auto-Ordnance. In 1919, the company began testing a prototype. They soon produced a production model unlike anything the world had seen. It could fire more than 600 rounds a minute. The weapon was fed from a 20-round stick magazine, or 50- or 100-round drum magazines. (Later versions had 30-round stick mags.) Because the powerful recoil from the .45 bullets tended to cause the Thompson to shoot high, a forward grip was added to help muscle the gun level.

They called it a submachine gun. Their reasoning was simple: the bullets it fired were smaller than what was in a regular machine gun, and the words “sub-calibre gun” had already been taken, thankfully.

Thompson contracted with Colt to produce 15,000 guns, and waited for the orders to pour in.

But Thompson had missed his moment. With the “War to End All Wars” over, no one needed a “trench sweeper.” Sales stunk. Despite Thompson’s insider connections and impressive live-fire demonstrations, the U.S. Army didn’t bite. The Navy and Marines came through with small orders here and there, but Thompson’s Auto-Ordnance Corporation limped along on the fringe of the firearms industry. Local police forces mostly shrugged. To them the gun looked like overkill, literally and figuratively. And at two hundred dollars, it wasn’t an impulse buy, for them or most private citizens either.

Then, suddenly, the Tommy gun became popular for all the wrong reasons.

It turned out the Thompson was the perfect tool for gangsters hoping to make an impression on their rivals. Small, portable, the weapon made one man into an army. In the hands of hit men and bank robbers, the power and psychological shock of the spray gun could rearrange an underworld command chain in a heartbeat. Instead of the trenches for which it was designed, the Tommy gun came to rule the back alleys of American cities.

General John T. Thompson and his legendary gun.

Library of Congress

(top)

Thompson personally didn’t like the association, but few gangsters took the time to ask his opinion. And as he gradually stepped back from running the firm, the corporation pretty much told dealers to sell the gun to whoever wanted it.

Mobsters in Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and practically anywhere money was to be made from booze or gambling began shooting it out with submachine guns. The Tommy Gun Wars were fed by wheelbarrows of money, and just as much anger. One killing encouraged three others; revenge became as important as control.

Al Capone certainly wasn’t the only gangster whose boys relied on the Tommy gun, but his crew sure did have a Thompson fetish. In Brooklyn on July 1, 1927, Capone’s old boss Frankie Yale was intercepted and drilled with a hundred bullets by men in a Lincoln chase car. Yale and Capone fell out after Yale started hijacking booze Capone had bought from him, giving new meaning to the word double-dealing. Overkill was part of Capone’s payback: the message it sent, not so much to the dead Yale but everyone else, was

Cheat me and I’ll shoot you dead, then kill you some more.

It’s thought that some of the same mobsters who murdered Yale were behind the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago on February 14, 1929. In a real headline moment for American gangsters, six thugs (including the guy who kneeled to spray his Tommy gun at the front of Capone’s hotel) and one unlucky optometrist were lined up against a wall and machine-gunned to death, presumably on Capone’s say-so.

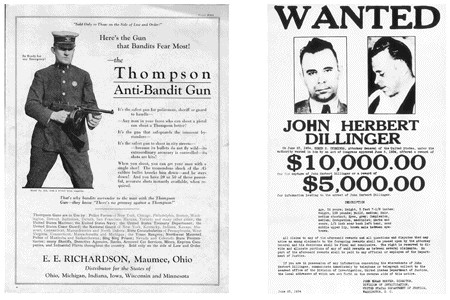

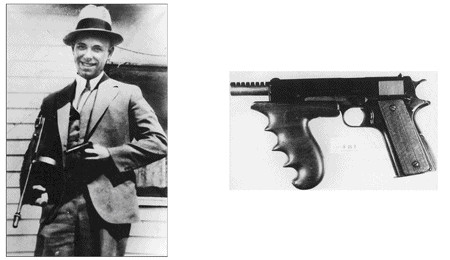

“There’s no getaway from a Thompson!” Above left: an ad promoting the Tommy Gun to police. Above right and below: John Dillinger and other gangsters were quick to adopt Thompson’s gun. Dillinger even added the forward grip from a Tommy to his modified M1911 pistol.

FBI

America’s most infamous public enemy of the era was undoubtedly John Dillinger, a Hollywood-handsome bank robber who used the Thompson as his withdrawal slip. The former Indiana farm boy was very polite when he robbed banks. He was even said to be genuinely sorry for the one policeman he’d killed with his Tommy gun. At least eleven others died during his crime spree at the hands of his fellow gang members.

But Dillinger had style.

“He liked to amuse bank customers with quips and wise cracks during holdups,” wrote author Paul Maccabee. “He would leap over the counters to show off his athletic ability and sometimes fired his Thompson submachine gun into the ceiling just to get people’s attention. Witnesses may have been robbed, but they got their money’s worth.”