America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (30 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

With Lee continuing to hold off the Army of the Potomac in a stalemate along the same battle lines at the end of 1863, Lincoln shook things up. In March 1864, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of all the armies of the United States. His first acts of command were to keep General Halleck in position to serve as a liaison between Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. And though it’s mostly forgotten today, Grant technically kept General Meade in command of the Army of the Potomac, even though Grant attached himself to that army before the Overland Campaign in 1864 and thus served as its commander for all intents and purposes.

Before beginning the Overland Campaign against Lee’s army, Grant, Sherman and Lincoln devised a new strategy that would eventually implement total war tactics. Grant aimed to use the Army of the Potomac to attack Lee and/or take Richmond. Meanwhile, General Sherman, now in command of the Department of the West, would attempt to take Atlanta and strike through Georgia. In essence, having already cut the Confederacy in half with Vicksburg campaign, he now intended to bisect the eastern half.

On top of all that, Grant and Sherman were now intent on fully depriving the Confederacy of the ability to keep fighting. Sherman put this policy in effect during his March to the Sea by confiscating civilian resources and literally taking the fight to the Southern people. For Grant, it meant a war of attrition that would steadily bleed Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. To take full advantage of the North’s manpower, in 1864 the Union ended prisoner exchanges, in an attempt to ensure that the Confederate armies could not be bolstered by paroled prisoners.

The Overland Campaign

Grant had already succeeded in achieving two of President Lincoln’s three primary directives for the ultimate Union victory: the opening of the Mississippi Valley Basin, and the domination of the corridor from Nashville to Atlanta. If he could now seize Richmond, he would achieve the third.

In May 1864, with Grant now attached to the Army of the Potomac, the Civil War’s two most famous generals met each other on the battlefield for the first time. Lee had won stunning victories at battles like Chancellorsville and Second Bull Run by going on the offensive and taking the strategic initiative, but Grant and Lincoln had no intention of letting him do so anymore. Grant ordered General Meade, "Lee's army is your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also."

By 1864, things were looking so bleak for the South that the Confederate war strategy was simply to ensure Lincoln lost reelection that November, with the hope that a new Democratic president would end the war and recognize the South’s independence. With that, and given the shortage in manpower, Lee’s strategic objective was to continue defending Richmond, while hoping that Grant would commit some blunder that would allow him a chance to seize an opportunity.

Lee

On May 4, 1864, Grant launched the Overland Campaign, crossing the Rapidan River near Fredericksburg with the 100,000 strong Army of the Potomac, which almost doubled Lee’s hardened but battered Army of Northern Virginia. It was a similar position to the one George McClellan had in 1862 and Joe Hooker had in 1863, and Grant’s first attack, at the Battle of the Wilderness, followed a similar pattern. Nevertheless, Lee proved more than capable on the defensive. From May 5-6, Lee’s men won a tactical victory at the Battle of the Wilderness, which was fought so close to where the Battle of Chancellorsville took place a year earlier that soldiers encountered skeletons that had been buried in (too) shallow graves in 1863. Both armies sustained heavy casualties while Grant kept attempting to move the fighting to a setting more to his advantage, but the heavy forest made coordinated movements almost impossible. On the second day, the aggressive Lee used General Longstreet’s corps to counterattack on the second day.

Grant disengaged from the battle in the same position was Hooker before him at Chancellorsville, McClellan on the Virginian Peninsula, and Burnside after Fredericksburg. His men got the familiar dreadful feeling that they would retreat back across the Rapidan toward Washington, as they had too many times before. This time, however, Grant made the fateful decision to keep moving south, inspiring his men by telling them that he was prepared to “fight it out on this line if it takes all Summer.”

[10]

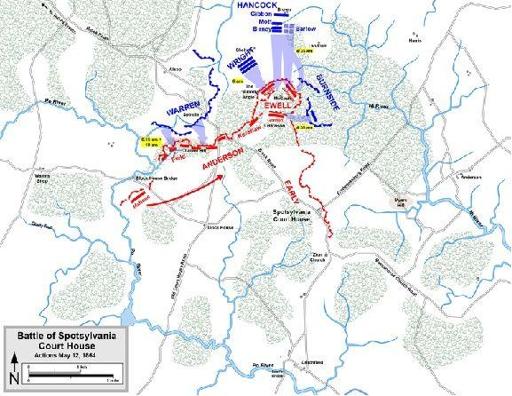

Using the Union V Corps under Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, Grant moved forward in a series of flanking maneuvers that continued to move the army steadily closer to Richmond. But Lee continued to parry each thrust. The next major battle took place at Spotsylvania Court House from May 8-21, with the heaviest fighting on May 12 when a salient in the Confederate line nearly spelled disaster. Fighting raged around the “Bloody Angle” for hours, with soldiers fighting hand to hand before the Confederates finally dislodged the Union soldiers.”

Lee’s army continued to stoutly defend against several attacks by the Army of the Potomac, but massive casualties were inflicted on both sides. After Spotsylvania, Grant had already incurred about 35,000 casualties while inflicting nearly 25,000 casualties on Lee’s army. Grant, of course, had the advantage of a steady supply of manpower, so he could afford to fight the war of attrition. It was a fact greatly lost on the people of the North, however, who knew Grant’s track record from Shiloh and saw massive casualty numbers during the Overland Campaign. Grant was routinely criticized as a butcher.

As fate would have it, the only time during the Overland Campaign Lee had a chance to take the initiative was after Spotsylvania. During the fighting that came to be known as the Battle of North Anna, Lee was heavily debilitated with illness. Grant nearly fell into Lee’s trap by splitting his army in two along the North Anna before avoiding it.

By the time the two armies reached Cold Harbor near the end of May 1864, Grant incorrectly thought that Lee’s army was on the verge of collapse. Though his frontal assaults had failed spectacularly at places like Vicksburg, Grant believed that Lee’s army was on the ropes and could be knocked out with a strong attack. The problem was that Lee’s men were now masterful at quickly constructing defensive fortifications, including earthworks and trenches, that made their positions impregnable. While Civil War generals kept employing Napoleonic tactics, Civil War soldiers were building the types of defensive works that would be the harbinger of World War I’s trench warfare.

At Cold Harbor, Grant decided to order a massive frontal assault against Lee’s well fortified and entrenched lines. His decision was dead wrong, literally. Although the story of Union soldiers pinning their names on the back of their uniforms in anticipation of death at Cold Harbor is apocryphal, the frontal assault on June 3 inflicted thousands of Union casualties in about half an hour. With another 12,000 casualties at Cold Harbor, Grant had suffered about as many casualties in a month as Lee had in his entire army at the start of the campaign. Grant later admitted, “"I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made...No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained."

Although Grant’s results were widely condemned, he continued to push toward Richmond. After Cold Harbor, Grant managed to successfully steal an entire day’s march on Lee and crossed the James River, attacking the Confederacy’s primary railroad hub at Petersburg, which was only a few miles from Richmond. By the time Lee’s army reached Petersburg, it had been defended by P.G.T. Beauregard, but now the Army of Northern Virginia had been pinned down at Petersburg. The two armies dug in, and Grant prepared for a long term siege of the vital city.

The Siege of Petersburg

Grant had not won a single victory during the Overland Campaign, and though his strategic objective of attacking Lee and taking Richmond was still in the process of being accomplished, Grant’s results certainly weren’t helping Lincoln’s reelection prospects, with Democrats hammering him for the staggering costliness of the war. Instead, it would be the scourge of the South who saved the day. With Grant in the East, control of the Western theater was turned over to William Tecumseh Sherman, who beat back Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood in the Atlanta campaign, taking the important Southern city in early September. On September 3, 1864, Sherman telegrammed Lincoln, “Atlanta is ours and fairly won.” So was Lincoln’s reelection two months later.

While Sherman took Atlanta and began his famous “March to the Sea”, Grant and Lee continued to hunker down at Petersburg, with the Army of the Potomac gradually expanding the siege lines and moving them closer in an attempt to fatally stretch Lee’s defenses. While Grant held Lee and his armies in check, Sherman’s army cut through Georgia and cavalry forces led by General Phillip H. Sheridan destroyed railroads and supplies in Northern Virginia, particularly in the Shenandoah Valley. Lee had almost no initiative, at one point futilely sending General Jubal Early with a contingent through the Shenandoah Valley and toward Washington D.C. in an effort to peel off some of Grant’s men. Though Early made it to the outskirts of Washington D.C. and Lincoln famously became the only president to come under enemy fire at Fort Stevens, the Union’s “Little Phil” Sheridan pushed Early back through the Valley and scorched it.

Sheridan

The siege would carry on for nearly 10 months, and during the siege the famous battle during took place when Union engineers burrowed underneath the Confederate siege lines and lit the fuse on a massive amount of ammunition, creating a “crater” in the field. But even then, the Battle of the Crater ended with a Union debacle, as Union forces swarmed into the crater instead of around it, giving the Confederates the ability to practically shoot fish in a barrel.

Still, by the beginning of 1865, the Confederacy was in utter disarray. The main Confederate army in the West under John Bell Hood had been nearly destroyed by General Thomas’s men at the Battle of Franklin in late 1864, and Sherman’s army faced little resistance as it marched through the Carolinas. Although Confederate leaders remained optimistic, by the summer of 1864 they had begun to consider desperate measures in an effort to turn around the war. From 1863-1865, Confederate leaders had even debated whether to conscript black slaves and enlist them as soldiers. Even as their fortunes looked bleak, the Confederates refused to issue an official policy to enlist blacks. It was likely too late to save the Confederacy anyway.

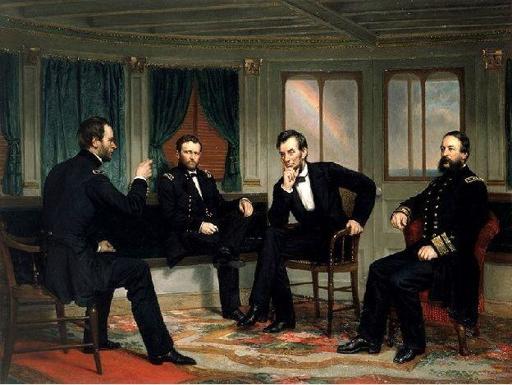

By the time Lincoln delivered his Second Inaugural Address in March 1865, the end of the war was in sight. That month, Lincoln famously met with Grant, Sherman, and Admiral David Porter at City Point, Grant’s headquarters during the siege, to discuss how to handle the end of the war.