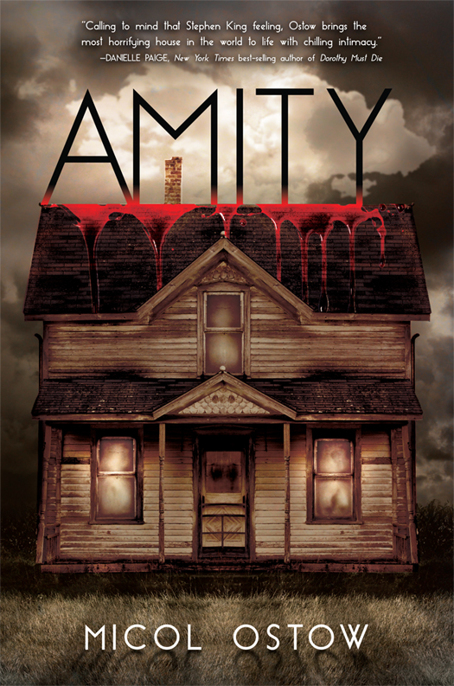

Amity

Authors: Micol Ostow

EGMONT

We bring stories to life

First published by Egmont USA, 2014

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 806

New York, NY 10016

Copyright © Micol Ostow, 2014

All rights reserved

www.egmontusa.com

www.micolostow.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ostow, Micol.

Amity / Micol Ostow.

1 online resource.

Summary: Two teens narrate the terrifying days and nights they spend living in a house of horrors.

ISBN 978-1-60684-380-2 (eBook) — ISBN 978-1-60684-156-3 (hardcover)

[1. Haunted houses—Fiction. 2. Supernatural—Fiction.

3. Brothers and sisters—Fiction.

4. Family life—New England—Fiction. 5. Moving, Household—Fiction.

6. New England—Fiction. 7. Horror stories.] I. Title.

PZ7.O8475

[Fic—dc23

2013045748

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

v3.1

For Mom, Mazzy, and Lawsy—three fearless broads

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Here

Now

Ten Years Earlier: Day 1

Now: Day 1

Ten Years Earlier: Day 2

Now: Day 2

Ten Years Earlier: Day 3

Day 4

Day 5

Now: Day 6

Ten Years Earlier: Day 8

Now: Day 8

Ten Years Earlier: Day 11

Now

Before

Always

Now: Day 13

Ten Years Earlier: Day 15

Now: Day 16

Ten Years Earlier: Day 17

Day 18

Now: Day 20

Ten Years Earlier: Day 24

Day 28: (Always)

Now

Here

Acknowledgments

This inhuman place makes human monsters.

—Stephen King,

The Shining

PROLOGUE

HERE

Here is a house; bones of beam and joints of hardware, stone foundation smooth, solid as the core of the earth, nestled, pressed, cold and flat and dank against the hard-packed soil and all of its squirming secrets

.

Here is a house; sturdy on its cornerstones, shutters spread wide, windowpanes winking against the speckled prisms of daylight. Weather-beaten slats of knotted siding, drinking in nightfall. Tarred shingles surveying star maps, legends shared in the pattern of dotted constellations above

.

Here is a house; not sane, not sentient, but potent, poisonous, drenched with decay

.

Here is a house of ruin and rage, of death and deliverance, seated atop countless nameless unspoken souls

.

Here is a house of vengeance and power, land laid claim by

wraiths and ciphers, persistent and insistent, branded and bonded and bound

.

Here is where I live, not living

.

Here is always mine

.

NOW

Dear Jules:

The Halls moved out of Amity today

.

She told me. Amity did

.

Like a bat out of hell. Or

bats,

I guess, seeing as it was the four of them

—

Mr. and Mrs., and the kids, Luke and Gwen. Who aren’t really kids, you know, with Gwen being exactly my age

—our

age—and Luke barely a full year older. Not quite twins—not like us. But close enough, right?

Anyway: Gwen. I could tell Gwen was different right from the start. Something about the light in her eyes told me that she had ways of seeing that were … well, you know, different from normal people

.

I liked that about her. Of course. I like

different.

It reminds me of me

.

But Amity? Well

.

Amity doesn’t care much about different. Amity doesn’t care much about anything, does she? Amity just wants what she wants

.

Twenty-eight days. Barely a month. That’s how long they lasted, the Halls, at Amity

.

Exactly the same as us

.

—Connor

TEN YEARS EARLIER

DAY 1

IT WAS HOT ON THE DAY WE MOVED IN

, brutally hot, in that way that makes you feel almost crazy, sweat dripping into your eyes so bad you’re practically blind. When we first pulled up in the van, Amity glimmered so you could almost see the ripples of heat with your own eyes, like a mirage plunked down far outside a tiny New England town. It wasn’t a day for heavy lifting; only a crazy person would have tried moving all on their own, in that kind of weather.

But no one ever said that Dad wasn’t completely insane.

Even being so close to the water, the sun was near unbearable. When Jules whined, Dad fixed her with one of his looks. Dad was never known for his patience. Not like me. I can be very patient. When it’s useful, I mean.

Normal people would have hired movers, professional guys, to get the job done. But Dad said, “Why would I pay hard-earned money when we’ve got four pairs of hands among us?”

Yeah.

Four pairs

, so at least he wasn’t expecting Abel to do much lugging.

Abel was only six, but you kind of never knew with Dad.

I just hoped that even then, even little, my brother knew he was getting a pass. Dad wasn’t much for passes. This was definitely your onetime-deal kind of thing.

There were no onetime-deal passes for Jules, or for me. Seventeen, I wasn’t an athlete at all—team sports rubbed me the wrong way—but I was strong enough.

Strong enough for some stuff.

So there we were on moving day. Jules whined, Dad glared, Abel mewled, and Mom worried. And I hitched my shorts up, and wrangled a box marked

FRAGILE

in six different places. It made a clinking sound as I hiked down the drive and past Mom, who made a face at the tinkle of shattered glass.

Our first day in Amity, and things were already all falling apart.

MOM HAD BOUGHT THIS SIGN, I REMEMBER

.

Seriously, it was the stupidest thing. Like so stupid, I mean, that you almost had to feel all sorry for her for even having it. For, like, going into a store, and seeing it, and thinking,

Yes, I want

that,

I should have

that

thing

, and then paying real, actual money to own it. I can’t even tell you. I didn’t even know where you could find something stupid like that, a sign for a house.

A

MITY

, it said: this fake etching on a cheap, shiny, little fake-wooden plaque. She must’ve had it made up special, which made the whole thing even dumber. I didn’t know anyone whose house had a name. It was the kind of thing you’d see in a movie, like if someone were rich or whatever. But no rich person would buy something tacky like this.

We weren’t rich. I mean, we weren’t poor. Which I guess meant we were in the middle. Probably from the outside it looked like we were doing better than we really were. That was Dad’s thing—making sure we looked like we were doing better, doing well. God only knew what his sketchy “business” deals were. He had to sell off the Ford dealership downstate real quick, and I knew some neighbors had their own theories about his work. None of them were all that flattering.

But even with Concord being a little speck on the map, the kind of small town even small-town people are bored by, it was pretty, sort of. Like respectable. The kind of place you could maybe put down roots, not the kind of place you rushed to, all cowering in the dead of night, your stuff piled sky-high in the back of a pickup, no forwarding address left behind.

Concord was a respectable town, one of the oldest in the country. I guess Dad picked it thinking some respectability might rub off on us.

Also, the house came cheap. I didn’t know why at the time.

I didn’t care much about things like what a house cost, but I had to admit that Amity was nice. It was pretty big. Much bigger than our old place. In Amity, my bedroom was connected to Jules’s by a bathroom we had all to ourselves. That bathroom felt like a real, big-time luxury after sharing just a single john with Mom and Dad for so long. It had one of those ancient bathtubs with the heavy iron claw feet that looked about a hundred years old. Jules thought it was cute but I thought you had to wonder how many people had soaked their bones in a tub that old, and where those people were now. And Abel’s room was way down the hall, so for the first time in forever Jules and I wouldn’t be woken by him at the unholy crack of

what-the-sweet-living-Jesus

every day.

On the third floor, there was a room I hoped for a second would be a den or something, like for me and Jules to hang out in, especially since Dad wasn’t one for sharing the old remote in the family room. It would’ve been nice to have a space of our own just to, you know,

be

in. But Mom said it was going to be her “sewing room,” like we were living in a fifties sitcom,

so that was that. Never mind that I couldn’t remember the last time I saw her sew. Jules was always trying to get me to go easier on the old lady anyway.

Hanging that sign from the mailbox was Mom’s first and last sitcom moment at Amity, it turned out. And she never did spend any real time in that sewing room.

I remember moving day, and her linking the plaque through some hooks that’d been in the mailbox before we even arrived—I thought it was funny or just dumb luck or something that the hooks were already in, like they’d been waiting for us. Dumb luck didn’t come easy to Mom. Or me, or Jules, now that you mention it. Any of us. But Mom smiled as she slipped the cruddy little sign in place, and then stepped back, holding a hand flat over her gray-green eyes to shield them from the sun.