Amy & Roger's Epic Detour (14 page)

“Nice choice of rooms, Hillary,” he said with a faint smile. Maybe he was too tired to be embarrassed, but he wasn’t even blushing.

“I’m really sorry,” I said. “But they only had this one left—”

“It’s fine,” he said. “I’m going to change first, if that’s cool.” He headed toward the bathroom, carrying his duffel.

“Sure,” I said, still staring at the bed. When Roger closed the bathroom door, I looked in the mirror and saw that my blushing had more or less subsided. Then I checked out the room. It had been awhile since I’d been in a real hotel—the cabin in Yosemite didn’t count. It was nice, too—there was a memo pad on the desk in the corner of the room, with a yellow and black

BEEHIVE MOTEL

pen, and I took both, stashing them in my purse. As I did, it occurred to me that this was the first time I was staying in a hotel without my family. And I was in the honeymoon suite. With a college guy.

Just as I had this jarring thought, Roger came out of the bathroom, yawning, dressed in the same shorts-and-T-shirt combo he’d worn the night before. It wasn’t so startling, now that I’d known to expect it. Roger looked at the bed as well. “It seems a shame to wreck it,” he said, and I looked down at the rose petals and realized that they’d been arranged in the shape of a heart.

I looked away, grabbed my own suitcase, and headed for the bathroom. “I don’t think the Udells will mind,” I said as casually as I could. I closed the door behind me and leaned back against it, letting out a breath. I knew Roger was tired, but clearly he hadn’t been too tired to notice that the whole room had been set up with the expectation that the people staying in it would be having sex.

We were in the

honeymoon suite

. The expectation of sex was in the very atmosphere, like perfume, but less subtle. This was worse than sharing a bed in Yosemite, even if this bed was bigger. It was like there was an elephant in the room. An elephant that expected us to have sex. I could feel myself blushing again, and thanks to the bathroom mirror, I was able to have visual proof as well. Trying to think about other things, I looked around the bathroom and saw that the tub was built for two, with complimentary bubble bath and a small dish of rose petals waiting on the tub’s edge.

Stalling, and also taking advantage of the fact that this bathroom was in-suite, and not a five-minute walk through bear-friendly territory like it had been last night, I took a long shower. Then I got changed for bed, swapping the long-sleeved shirt I’d worn the night before for a T-shirt, figuring that it wouldn’t be as cold here. As I combed out my hair, I tried not to focus on how much hair was left behind in the comb when I finished. I just packed up my toiletries, adding in the bubble bath, the complimentary shampoo, the sewing kit, and the hand lotion.

When I came out of the bathroom, I saw that Roger was already under the covers on his side, with his eyes closed. So maybe he wasn’t bothered by any of the weird room pressure at all.

Roger had turned off all the lights but one, the small chintz-covered bedside lamp on the left side—my side. Trying to make as little noise as possible, I slipped under the covers and snapped off the light. I turned on my side and looked across at Roger, who was curled up, facing me. Sleeping next to him didn’t seem as scary to me as it had yesterday. Had it only been yesterday?

I watched him for a moment. Then, even though I was sure the night before had been a fluke, and I wasn’t going to get any sleep, I let my eyes close. “Good night, Roger,” I murmured.

After a moment, Roger surprised me by replying—I was sure he’d fallen asleep. “’Night,” he said. “But the name’s Edmund.”

There’s no surf in Colorado.

—Bowling for Soup

“Hi, it’s Amy’s phone. Leave a message and I’ll get back to you. Thanks!”

Beep.

“Amelia. This is your mother. I’m not happy that you didn’t call me back yesterday. I’m getting concerned, especially since none of the hotels seem to have a record of you checking in. Call me immediately.”

“Hi, you’ve reached Pamela Curry. Please leave a message with your name and number, and I will return your call as soon as I am able. Thank you.”

Beep.

“Hi, Mom. Wow, I guess we keep missing each other. Weird. But things are fine! There’s no need to be concerned. We, um, hit traffic outside of … Oklahoma, which we are way past by now. So we’ve been a little behind. But we’ve been finding hotels with no problem. And the driving is fine, and everything is going okay. So no need to worry!”

“Is it a man?” Roger asked me.

“Yes,” I said. “Sixteen.”

“Is he alive?”

“No. Fifteen.”

“Is he an explorer?”

“Only you would ask that. No,” I said.

“

You

ask me that every time.”

“Because you keep choosing explorers.”

“Fair point. Is he famous?”

“Yes. Fourteen.”

“Hmm.” Roger drummed his fingers on the steering wheel, and I curled my legs up under me and looked out the window.

The sun was just beginning to set—we’d been driving all day. We’d gotten a later start than we wanted because, to my shock, I had slept through the night again and was still fast asleep when the irate desk clerk called us at what I thought was ten. But since neither of us had adjusted for the time change, it was actually eleven, and we were in danger of getting charged for a late checkout. We’d hit the road and actually stopped along the way to sit down and eat both breakfast and lunch. I’d discovered that I loved diners, and Roger loved diner jukeboxes.

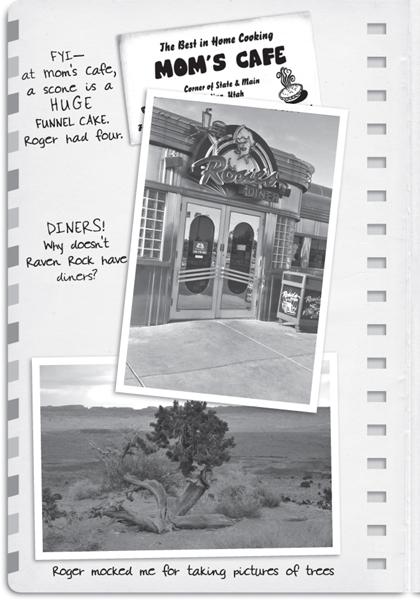

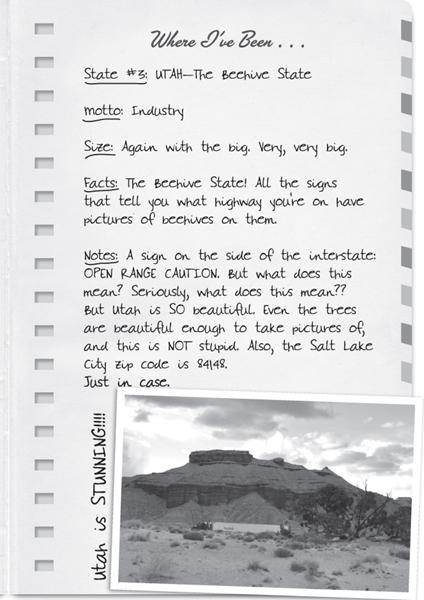

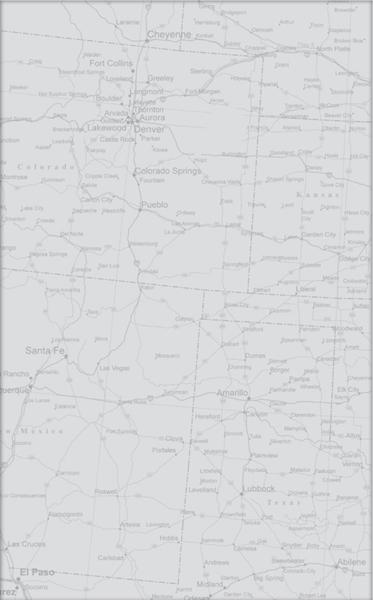

The drive through Utah—during which I’d learned that John Cabot had possibly discovered Canada and Roger learned who Stephen Sondheim was—was absolutely breathtaking. The scenery was even more stunning than it had been on Highway 50, mostly because there was now something to look at. And what there was to look at took my breath away. It was strangely otherworldish—these huge red plateaus and fantastic little drift-wood trees that I couldn’t stop taking pictures of, much to Roger’s delight, since he thought that taking pictures of trees was the most ridiculous thing he’d ever heard of. As it had been the day before, it was as though someone had opened up the landscape and you could just see forever, underneath a sky that, I swear, was bigger and bluer than it had been in Nevada.

Now that we were back on the interstate, we were seeing road signs again, and most of them were new to me. In addition to the inexplicable

OPEN RANGE CAUTION

, there were animal signs I’d never seen before—an antelope, a cow, and a cow with horns. There were deer signs too, but I’d seen those for the first time near Yosemite. But it worried me that, without warning, a cow with horns might be running across the interstate. And that this had happened frequently enough that they’d had to erect a sign to warn people about it.

As we crossed into Colorado, slowly but surely the landscape changed again. The open flatness we’d had in Nevada and Utah became more mountainous, and suddenly the pine trees were back. The grades of the incline were now posted on signs on the side of the road, and the road was getting more winding and much steeper as we crossed actual mountains. We’d climb and climb, and then go downhill sharply. The Liberty was fine with this, but it seemed that the steep grades were an issue for the truckers—especially the downhill grades. There were signs that I couldn’t believe were real, that seemed to offer truckers stream-of-consciousness support for these roads.

STEEP GRADE AHEAD, TRUCKERS! USE CAUTION!

and

TRUCKERS! IT’S NOT OVER YET! MORE 6% GRADE AND WINDING ROADS

! The one that I stared at the longest, however:

IF BRAKES FAIL, DO NOT EXIT. STAY ON INTERSTATE

. I mean, what? That seemed like terrible advice to me, and whenever we were behind a truck, I found myself watching its brake lights, making sure they were flashing red.

Roger had been getting quieter the closer we got to Colorado Springs. At both diners, he’d left during the meal to make phone calls, calls he made clear he didn’t want to talk about when he returned to the table and immediately changed the subject. I’d almost asked, the first time, if he’d been calling Hadley, but then realized that would involve admitting I’d heard his conversation at Yosemite.