An Evening with Johnners (19 page)

Read An Evening with Johnners Online

Authors: Brian Johnston

B

ut the story about doing what is right or what is wrong concerns one of those marvellous matches at Arundel, which the Duke used to run against local teams. He was running one against Sussex Martlets and they had an eleven o’clock start in those days. At a quarter to eleven they were an umpire short, so the Duke said, ‘All right. I’ll go down to the Castle and get my butler, Meadows.’

So he got in his shooting brake with the Labrador lying in the back, drove down to the Castle and went through

the green baize door into the pantry. There was Meadows the butler, polishing the coronets and the silver. The Duke said, ‘Meadows, take your apron off, put a white coat on and come and umpire.’

So, reluctantly, Meadows did, although he didn’t know much about cricket. It was one of those days of gentle drizzle, not wet enough to stop, but making the ground very slippery and difficult. The Duke’s team were batting, one hundred and ten for eight, and the Duke came in at number ten and went to the non-striker’s end. The chap batting thought, I’d better let him have the bowling, so he pushed one to cover and said, ‘Come on, Your Grace, come one.’

His Grace set off, but he slipped up and landed flat on his face in the middle of the pitch. Meanwhile cover point picked the ball up and threw it over the top of the stumps. The wicket-keeper whipped off the bails, turned to the square leg umpire and said, ‘How’s that?’

The square leg umpire, inevitably, was Meadows the butler. What was he to do? He knew what he ought to do and there was his boss, who wouldn’t be too pleased, but he stuck to his principles.

He drew himself up to his full height and said, ‘His Grace is not in!’

A

propos of that, when I was in Australia with Peter May’s team, there was an umpire who wasn’t very good. His name was McInnes and on the previous tour with Len Hutton he’d been very good indeed, but somehow he had failed. He made one or two bad mistakes.

Tom Crawford, who used to captain Kent second eleven and was a great friend of mine, was talking to Don Bradman about this.

‘The trouble with your umpires, Don,’ he said, ‘is that they’ve never actually played Test cricket or even Shield cricket. They’re not first-class cricketers. They’ve learnt all the laws and passed exams, but they don’t know what goes on in the middle. At home, all our umpires are either Test players or County players.’ (That was true then, but I think we’ve got some now who aren’t.)

Don got very indignant about this. ‘No, no,’ he said. ‘What about McInnes? He played for South Australia until his eyesight went.’

Then he realised what he’d said!

N

ow I’m going to lunch at the Savoy on Wednesday with the Australian team, and I shall tell them the story which was told by the best after-dinner speaker I ever heard, the late Lord Justice Birkett. He told it in 1953 to Lindsay Hassett’s team and said how welcome they would be wherever they went in the British Isles.

‘But,’ he said, ‘one word of warning, we don’t wear our hearts on our sleeves in this country. We are a bit cool and reserved; we often don’t know the chap next door, even though he’s lived there for forty-five years. But don’t worry, on the surface we may not be friendly, but

underneath

it we are. Indeed, we treat each other exactly the same.’

He then told the famous story of the Flying Scotsman leaving Kings Cross non-stop to Edinburgh. Four men were reading papers in the corner of a carriage. They glided through the Hertfordshire countryside and after thirty-two miles, got to Hitchin. One of them put down

The Times

that he was reading and said, ‘Look, we’ve got three hundred and eighty-four miles to go. Let’s talk and get to know each other and the journey will go so much more pleasantly. I’ll tell you about myself. I’m a Brigadier, I’m married and I’ve got one son who’s a banker.’

The chap sitting opposite him put down his copy of

The Times

and said, ‘You won’t believe this. I’m also a

Brigadier

, I’m married and I’ve got a son who’s a schoolmaster.’

The third chap said, ‘Well, this is the most amazing coincidence,’ and he put down

his Times.

‘I’m a Brigadier, I’m married and I’ve got a son who’s a lawyer.’

They all looked at the fourth chap, who was reading the

Sun

, and they said, ‘What about you?’

He said, ‘I’d rather not,’ so they went on talking amongst themselves.

They got to a little place called Sandy, about fifteen miles up the line, and they turned to this chap and said, ‘Come on, join in. We’re having so much more fun.’

He said, ‘No, I don’t want to.’

‘Come on,’ they said, ‘be a sport.’

‘All right, have it your own way,’ he said. ‘I’m a

Regimental

Sergeant Major. I am

not

married. I’ve got three sons – and they are all three Brigadiers!’

T

here are other things about cricket: we’re told there’s a lot of pressure these days, and people do get irritated, aggravated and frustrated, but I think it’s dreadful, because, as I say, it should be fun.

A father I knew was trying to teach his boy the right way to play cricket and he said, ‘Never get irritated.’

The boy said, ‘What’s irritation, Dad?’

So the father said, ‘Well, I’ll teach you about

irritation

, aggravation and frustration.’ He got a telephone

and dialled a number at random and a man’s voice said, ‘Hello?’

‘Is Alf there?’ said the father.

‘No,’ said the man, ‘Alf doesn’t live here,’ and

bang

he put the phone down.

The father said, ‘That man’s a bit irritated, son.’

‘What about aggravation, Dad?’

‘All right,’ he said, and dialled the same number again.

The man’s voice said, ‘Hello?’ and the father said, ‘Is Alf there?’

‘No, Alf isn’t here! Are you the same man who rang just now? If you don’t ring off, I shall get the police!’

Bang

.

‘He’s very aggravated now, son,’ said the father.

‘Yeah, but what about frustration, Dad?’

So the father dialled the same number. The man’s voice said, ‘Hello?’

The father said, ‘It’s Alf here. Have there been any calls for me this morning?’

T

he other thing is: don’t panic. There’s nothing more awful than seeing a cricket team panicking. I love

Corporal

Jones in

Dad’s Army

: ‘Don’t panic! Don’t panic!’ And there’s a perfect example of how not to panic.

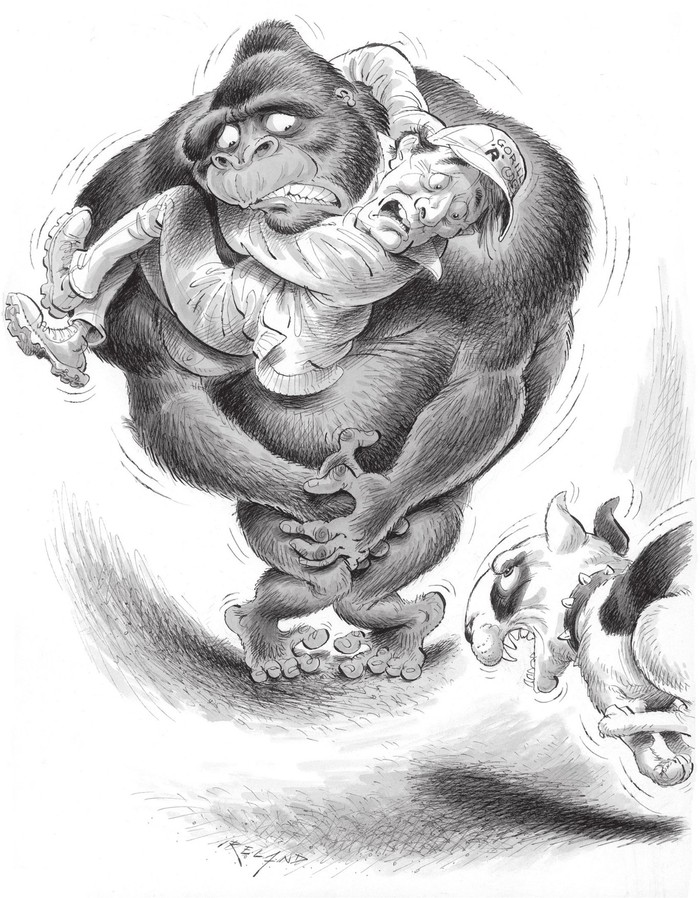

A chap woke up one morning, drew his curtains, looked out of the window and saw, to his horror, a gorilla in a tree in his garden. Well, he didn’t panic, because he went straight to the

Yellow Pages

, dialled a Gorilla Catcher and said, ‘I’ve got a gorilla in my tree.’

‘No problem, sir, I’ll be round in quarter of an hour.’

A quarter of an hour later, a little yellow van arrived and out of the back of it the gorilla catcher took a ladder, a pair of handcuffs, a shotgun and a bull-terrier. So the chap said, ‘What are all these things for?’

‘Oh, it’s quite easy,’ said the gorilla catcher. ‘I put the ladder against the tree, I climb it and shake it. The gorilla will then fall to the ground. Now, at that point, I want you to release the bull-terrier, who is trained to bite human beings and gorillas in a very painful place.

‘The gorilla knows this and to save himself, will put his hands down over his private parts. You run forward, put the handcuffs on him, and you’ve got him.’

‘That’s all right,’ said the chap, ‘but what about the shotgun?’

‘Oh,’ said the gorilla catcher, ‘I forgot to tell you about the shotgun. Sometimes, when I climb the ladder and shake the tree,

I

fall down. In that case, get the shotgun and shoot the bull-terrier!’

N

ow there’s one more story that my young ten-

and-a

-half-year-old grandson, Nicholas, told me. It’s

extraordinary

the stories they come back with from school!

This was about three football fans, an Englishman, a Scotsman and an Irishman. They were stranded in the desert. I don’t know what they were doing in the desert, but they’d been there for a week. They were very hungry and they came across a dead camel, so they decided to cut it up and eat it.