An Evening with Johnners (17 page)

Read An Evening with Johnners Online

Authors: Brian Johnston

N

ow humility. I think humility is very important and I learnt the hard way. I wasn’t a bad wicket-keeper and I wasn’t a good one. I was just so-so in club cricket, but I loved it and I played an awful lot. After the war – again, how lucky could I be – when I was in the BBC, there was no John Player, Refuge Assurance, Sunday League, or whatever it’s called now. So you could get all the Test players, and all the visiting teams, to play charity matches on a Sunday.

I kept wicket for fifteen years after the war to all the great bowlers – Lindwall, Laker, Lock, Trueman, Miller, Bedser – you think of anyone, I kept wicket to them. Great fun for me, not much fun for them!

But they were very kind to me. I remember once Jim Laker was bowling, he was absolutely marvellous, you didn’t realise what a great bowler he was until you kept wicket to him. Every ball had tremendous bounce.

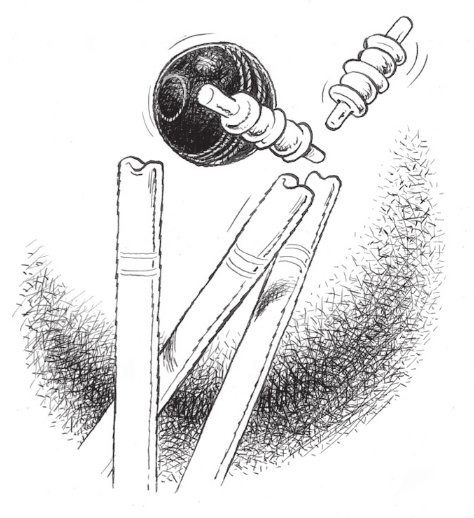

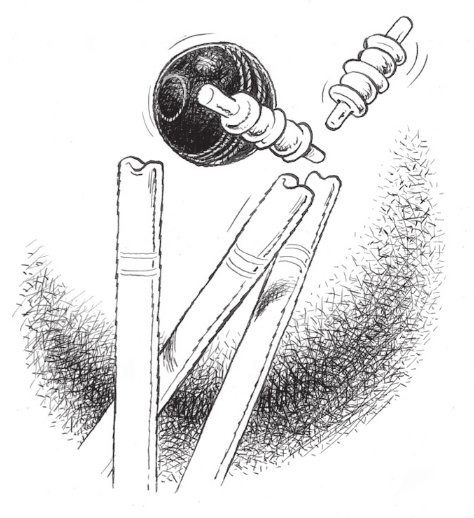

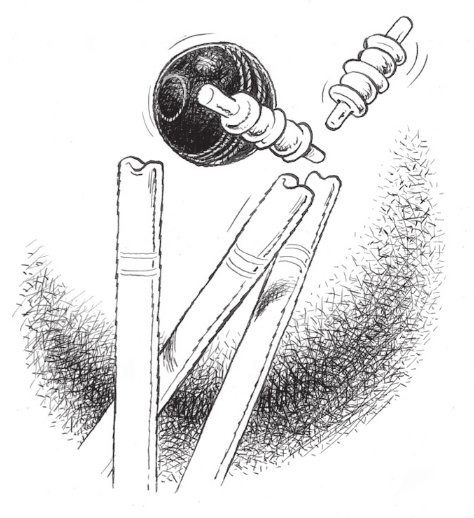

So he bowled a ball and the batsman went right down the pitch and I thought, Ah, off-spin bowler – Johnston, get outside the leg stump for a leg-side stumping.

There I was, waiting, and of course, it was the one which went to the arm and went for four byes, but he didn’t mind.

P

eople were kind, but I came down to earth with a bump. I began to think I was getting rather good, playing in these matches, and we went to the Dragon School at Oxford where Richie Benaud, the Australian captain, was playing and I was keeping wicket. He was bowling his flipper and his googly and his top spinner and his leg break. I was reading them all well … they all went for four byes, but I read them well!

Then the last chap came in and Richie bowled him a tremendous leg break. This chap went right down the pitch, missed the ball by

that

much, and it came into my gloves. With all my old speed, so I thought, I flicked off the bails, just like that, and the umpire said, ‘Out!’

A great moment for me, a club cricketer, stumping someone off the Australian captain. So I was looking a bit pleased with myself when I walked off the field and the bursar of the school came up and said, ‘Jolly well stumped.’

‘Thanks very much,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ he went on, ‘I’d also like to congratulate you n the sporting way you tried to give him time to get back!’

O

f course, in cricket, if you are a captain you have to have a lot of tact, and being tactful isn’t very easy. You have to think very quickly sometimes. A chap the other day was talking to another man and they got on to the subject of Brazil and the first man said, ‘Oh, Brazil! It’s just a nation of prostitutes and footballers.’

‘I’ll have you know, sir,’ said the other chap, ‘my wife was born in Rio de Janeiro and she’s a Brazilian.’

The first man thought very quickly and said, ‘I was just about to ask, which football team did she play for?’

S

o that is tact, which you must have as a captain, and leadership is so vital. I’ve been lucky to commentate with some great captains and two of the great ones, certainly, came from Australia – Bradman, who had a very good side to captain admittedly, except in 1938 – and Richie Benaud, one of the best.

If I pick English captains – Norman Yardley was just too nice to be a great captain, but he was a very good

tactician and got the best out of his people and was a great reader of pitches.

Ray Illingworth is my choice for the best all-round captain – determined to win, a great tactician and the men would follow him. He was great.

In later years we’ve had Mike Brearley; and Graham Gooch, leading from the front – not a great tactician but leading by example, and he certainly worked wonders.

But take Mike Brearley. You see, everybody’s different and Mike Brearley, a psychoanalyst, studied the character of each member of his side, to get the best out of them. Tough with one, more gentle with another, so he got the best out of his side. There’s a great example of this.

In 1981, that famous match – ‘Botham’s Match’ at Headingley – England had to follow on. Botham hit one hundred and forty-nine not out. Graham Dilley went in and made his first fifty in first-class cricket, in a Test match, and Chris Old made thirty odd. In the end,

England

recovered so that Australia had to make only one hundred and thirty to win. Still, they had to make it.

Godfrey Evans, on behalf of Ladbroke’s, offered five hundred to one against England, and two people took it. Lillee and Marsh of Australia!

At the beginning of that innings at Headingley, Botham bowled downhill, downwind from the Kirkstall Lane end, took a wicket and was off after about five overs. And trundling upwind and uphill from the Football Stand

end was Bob Willis, aged thirty-two then, the fastest man in the side.

Botham came off and Chris Old took over from him. Willis was relieved after about half an hour, and a quarter of an hour later was switched round, came in downhill, downwind and bowled faster and fiercer than I’ve ever seen him. He took eight for forty-three and England won by eighteen runs.

I remember going up to him afterwards and I said, ‘Look, Bob, why did you have to bowl uphill, upwind?’

He said, ‘I wondered the same thing. So I went up to Mike Brearley and I said, “Skipper, why am I bowling uphill, upwind?” And Brearley said, “To make you

angry.

”’

Now that is captaincy – and it worked!

B

ut there’s a different sort of captain I rather like – Keith Miller, the jovial chap from Australia. A marvellous figure of a man. He loved hitting sixes, bowling bouncers and backing horses. He loved women and they loved him. He didn’t worry much about tactics or laws, but

he just enjoyed playing with his friends on, and off, the field.

There’s a lovely story about him. He didn’t captain Australia, but he captained New South Wales once and he was leading them out, walking twenty yards in front, a majestic figure, tossing his hair – I can’t toss my hair, but he did.

A chap called Jimmy Burke who, alas, is no longer with us, ran up and tugged his sweater and said, ‘Nugget!’ (He used to call him ‘Nugget’) ‘Nugget, Nugget, we’ve got twelve men on the field!’

Miller didn’t pause. He went walking on and said, ‘Well, tell one of them to bugger off then!’

U

mpires! I support umpires more than one hundred per cent, if one can do such a thing. I think they do a wonderful job. It’s a very difficult one and they have a rotten time these days, especially on television. I hope not so much in club cricket. The dissent shown is awful and the appealing, when it obviously isn’t ‘out’, but they

are very much handicapped by this awful thing – the action replay.

In Australia, and they tried it once at Headingley, they show the match on a big screen, and after a decision has been made you can see it replayed on the screen. The wretched umpire has to give a decision in a split second – well, he might take a bit longer, but not much – while the commentators can say, ‘Let’s have a look at that replay. Hmmm, I’m not sure. Let’s have a look from another angle.’

They take about three looks before

they

can decide, so it is unfair on the umpires and I think it makes their task very difficult.

Incidentally, talking about action replays. Did you hear about the Irishman? Caught a brilliant catch at third slip.

Missed it on the action replay!

Seriously, I’m in favour of having a third chap in the pavilion for run-outs only. Because I was talking to one of our first-class umpires, who actually made a very bad run-out decision last year, which he knows he made.

‘But,’ he said, ‘it is very, very difficult. You’re standing at square leg, the batsman is coming and you’ve got to watch for his bat and the popping crease. You’ve also got to be slightly cross-eyed and watch the stumps to see that the wicket-keeper doesn’t mishandle it or that it actually hits the stumps

and

you’ve got to know, when it hits the stumps, where the bat is!’

It

is

very, very difficult and mistakes are often made, so I’m in favour of run-outs being done on the action replay.

B

ut umpires are treated very badly. I’ll tell you two stories which should never have happened. The first one concerns Gilbert Harding. Many older people may remember Gilbert Harding on the television programme

What’s My Line

– crusty, a brilliant brain, but very

intolerant

of other people’s ignorance. He was a bit rude to them, but he used to send them flowers the next day!