Anatomy of Fear (17 page)

I played with the projector’s lens to enlarge it as much as possible.

What is it?

I slipped the picture out of the projector and remembered where I had seen it. But it didn’t make any sense.

Out in the hall Denton was nowhere in sight. Chief of Operations Mickey Rauder was talking to Terri, and he signaled me over.

“Nice work,” he said. “Your old man would have been proud.”

The sentence stopped me cold, though I could see he was waiting for me to respond. “You knew my father?”

“Yes, we were in the same division, Narcotics, way back when.” He squinted at me. “You look like him.”

Did I?

I had never allowed myself to think so.

“Juan Rodriguez was a good man.”

I nodded, unable to locate my voice.

“Guess I’m one of the few cops who decided to stay way past when most cops retire, but it paid off. Here I am chief of operations. Some days I can hardly believe it, but if you stay in long enough you never know.”

I managed to say, “Uh-huh,” looked past the man’s basset-hound wrinkles to see he was younger than I’d originally thought, mid-fifties, like my father would have been.

“I think your old man would have stayed too.” He squinted at me again. “Can’t get over how much you look like him.”

I nodded again, hoping he would just stop talking.

But he wouldn’t quit. “I was thinking back there in the briefing room how your father would bring your drawings into the station and hang ’em up. He was so damn proud of you.”

Mickey Rauder waited for me to say something, but when I didn’t he slapped me on the back, said he hoped to see me around, to keep up the good work, and left me standing there with tears burning behind my lids and my heart in my throat.

Y

ou okay?” Terri asked.

“Yeah, fine.”

“Good. There are a few things I want to go over with you.”

“Later,” I said, and took off.

I headed out of the precinct with a picture of my father so strong in my mind that he could have been walking right beside me.

I

shuttled crosstown from Times Square to Grand Central, then and waited on the subway platform for the number 6 train. It seemed to be taking forever. I kept looking down the tunnel, impatient, highlights of Mickey Rauder’s conversation reverberating in my head.

You look like your old man…He was so damn proud of you…

When the train finally pulled into the station I was so lost in reflection, it startled me.

I gripped an overhead bar and stared at an ad for whiter, brighter, teeth without seeing it, the drawing of Carolyn Spivack shimmering in my brain.

What I was thinking did not seem possible, but I was going to check it out.

M

y grandmother was waiting at her front door as I came out of the fifth-floor stairwell. I was puffing for breath.

“The elevator,

está roto

?”

I shook my head, took a few deep breaths. “No, I, uh, just wanted the exercise.”

She gave me a look.

“¿Qué te pasa?”

“

Nada, uela.

Everything’s fine.”

“

Estás mintiendo.

I see it in your eyes.”

My grandmother read faces better than I did.

“I just need to see something.” I leaned down to kiss her cheek.

She laid her hand on my arm.

“¿Cuál es el problema?”

“There’s no trouble,

uela

. I just need to get my drawing pad.”

She planted her hands firmly on her hips. “You don’t have another at home?”

“I just want to see something, is that okay with you, officer?”

“Oye, chacho.”

She waved a hand. “You are such a

mentiroso.

”

She headed to the small hallway closet where I kept my pad and pencils, but I beat her to it, grabbed my pad, and hugged it to my chest. I wanted to look in private.

She pursed her lips and narrowed her eyes.

“You will have something to eat.” It was not a question.

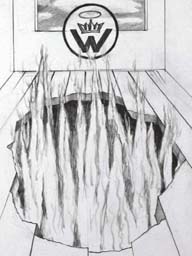

I went into the living room and sat down on the couch. My hands were shaking as I opened the pad to the last drawing I had made, the one of my grandmother’s vision.

I took out the copy of the sketch found at Carolyn Spivack’s crime scene

and an enlargement of the symbol on her belt that I’d made after I’d seen it projected on the briefing room wall.

I had not been wrong. But how was it possible? It had to be some totally weird coincidence—the same symbol in the CS drawing and in my grandmother’s vision.

My grandmother called out from the kitchen:

“¿Quieres algo de tomar, cerveza?”

I knew she just wanted to see what I was up to, but I said yes.

A minute later she was handing me a Corona.

She leaned over the couch. “What is so

importante

about this drawing pad?”

I had already closed it and hidden the copies of the crime scene drawings.

“I just wanted to check something.”

“¿Qué?”

“Since when are you a detective?”

“Siempre.”

“Always is right.” I had to smile. “Okay.” I opened the pad.

She looked at the drawing and crossed herself. “I told you, the

ashe

in that room is no good.”

“Yeah, I remember that. But what does the symbol mean?”

“

Yo no sé.

It just appeared to me.” She sat down beside me.

“¿Por qué?”

I could never hide my feelings from her. I wasn’t sure I wanted to put too much stock in her visions, but this was undeniable.

I was suddenly thinking back to the day before my father died. I’d been up on the roof of the building, Julio and I smoking a joint, listening to salsa music coming from open windows. When we came back into the apartment, there were lit candles everywhere and glasses filled with water at the

bóveda.

When I asked my grandmother why, she had waved me off.

I didn’t want to stir up old grief, but had to ask. “The day before

papi

died you lit candles and filled the

bóveda

glasses. Why?”

“Hace mucho tiempo.”

“

Sí,

it’s a long time ago,

uela,

but I need to know.”

“Why you want to know now?”

I looked at her and waited.

She took a deep breath. “I had a vision,” she said. “The night before…before it happen.” She described the vision, and I saw it.

It was all I needed to bring me back to that night twenty years ago.

I

had begged Julio to come home with me, even kidded him. “Yo,

mira,

you’re supposed to be my bodyguard,

mi pana,

right? But he wouldn’t do it.

When I got out of the subway at Twenty-third and Eighth, the streets were deserted; no music in the air, no hydrants spraying diamonds into the gutter. Just a drunk collapsed in front of a deli, and steam rising off the pavement.

I headed up the two short blocks to Penn South. There were only a few windows lit, and I didn’t have to count the floors to know that it was my apartment, my parents waiting up for me. My mother had been at work when the shit had gone down between me and my father. By now, she had to know.

I chewed a piece of Dentyne to mask the booze and dope.

The apartment complex was quiet, the lobby empty. When I got off the elevator I could see light under the apartment door.

I knew I was in for it. I took a couple of deep breaths and opened the door.

There were two men standing there, detectives who worked with my father. The minute my mother saw me she started crying.

At first I thought the cops had come looking for me, but that wasn’t it. She asked them to tell me. She couldn’t speak.

Your father’s been shot,

said one of the cops.

Looks like a drug bust gone bad,

said the other.

Must have happened spontaneously, something going down that he tried to stop.

The cop laid his hand on my shoulder and said my father was a brave man.

I had to ask. And they told me.

Two shots in the chest. One in the head.

But only I knew what had happened—that it had been my fault.

I never told my mother. How do you tell your mother that you killed your father, her husband?

I

forced the memory out of my head and listened to my grandmother.

She said that after she had the vision she’d sought out the gods. She should have warned him, but knew that her son, a nonbeliever, would have scoffed at the warning.

“Still,” she said, “I should have tried.

Es un arrepentimiento.

” There were tears in her dark eyes.

I wanted to tell her that it had been my fault, not hers, but couldn’t find the words.

She patted my hand and started talking about the

egun,

the dead, and how they interact with the living. We all have a specific number of days on earth, she told me, and those who are killed before that allotted time hang around as ghosts until their time is up, until their souls, their

ori,

can rest.

I wondered if my father’s

ori

was looking for me.

She tapped my drawing and her face grew dark. “There is something in that room,

algo malo.

” She looked up at me. “And now you are here to see it again.

Por qué?

”

“It’s nothing,

uela,

like I said.”

“Nato,

por favor,

do not lie to your

abuela.

”

“It has to do with a case at the police station, that’s all. It doesn’t concern me, not personally.”

My grandmother’s face showed me I was wrong. “You must stay away from this case, Nato.

Es muy peligroso para tí.

”

“

Sí,

it is dangerous,

uela,

but not for me.”