Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (37 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

But at the time of her writing, Anne had no home. North Haven and Next Day Hill no longer existed as Anne remembered them; she would not return to Hopewell. The “home” she left in the summer of 1931 was the scene of her childhood, full of a loving and enveloping family, which could never be the same. Her father was dead and her son had been murdered. Nonetheless, Anne knew that she must find her way back to the “knot,” which fastened her faith to life before they died, if she were to make sense of her experience and go forward with hope. She had to return to the innocence that belied her vulnerability in order to unravel its “mysteries.”

Implicit in Anne’s narrative is the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Anne is Ariadne, the king’s daughter, who waits at the entrance of the Labyrinth for her hero to return, guided by the ball of thread she has given him. But Anne’s Ariadne is a technological heroine in a technological age, with the skill and freedom to ride alongside her prince, capable of as much conquest as he. Anne is at once the lovesick maiden and the agent of their safe return. She, like Ariadne, devises

the plan that brings them home. This is Anne’s moment of triumph—the story that renews her faith and hope.

The Lindberghs’ seven-thousand mile flight, which soared above geographic and cultural boundaries, is the perfect metaphor for her psychological journey. Isolated in her sorrow, Anne uses the narrative to rail against a universe indifferent to human suffering. Through the art of narrative, she grieves and searches for reconciliation. It is a “daydream” in the Freudian sense, a creative vision in which the author splinters her psyche into literary representations whose conflict and resolution will make her whole.

Anne is both the protagonist and the narrator, the observer and the heroine. The people she meets on her flight are pilgrims; each a different person to test her virtue and teach her lessons.

At their first stop, Baker Lake, an isolated trading post on the flatlands of the Northwest Territory, Anne is the first white female the Eskimos have ever seen and the first woman to visit the European fur traders at their camp. As if reinventing herself through their eyes, Anne examines the Victorian notions of the feminine ideal, the symbol of delicate beauty, moral purity, and “home.” Laughing at the discrepancy between herself and the symbol, Anne probes the universal need for intimacy and security. Like the animals they trap, the traders at Baker Lake burrow beneath the ice, hiding from their feelings in order to survive the loneliness. Anne becomes the object of their projected fantasies; they treat her as warmly as if she were sister, mother, or wife. A feminine ideal, Anne cracks their icy surface with the magical power of her words. Language, she concludes, can crystallize memories raised from the dark seas of the unconscious.

They fly deeper through the white summer nights of the Northwest Territory to the Mackenzie delta, on its northern shore. There, in the bleak and frozen land, Anne feels like an exile in time and space. They stop at Aklavic, a sophisticated settlement of twenty-eight houses and two churches in frequent contact with the “outside world.” Unlike the people of Baker Lake, the Eskimos and settlers here have radio apparatus

and are visited yearly by a boat that brings letters and packages, food and dry goods from the mainland. To Anne, the arrival of the boat seems to symbolize the longing of men, women, and children for the comfort and possessions of “home.”

As they span the Arctic Sea to the northernmost part of the Alaskan peninsula, Port Barrow, they are enveloped by fog. In the gray half-light of the Arctic sun, as they move farther into an abyss, Anne loses hope of arrival or retreat. Aided by the good will and competence of the stationmaster at Point Barrow, they blindly climb the walls of white fog. Once again, in exile in a barren and icy land, Anne explores the power of the spoken word. Their host, a doctor, is also a preacher who translates portions of the New Testament into the language of the Eskimos. Through the doctor’s renditions of biblical stories and hymns, Anne confirms her need for a connection to a spiritual force, one that transcends the particularity of culture and language. Words, while they are limited instruments of human experience, connect not only man with man but man with God.

Their next stop is Nome, an old mining village on the south coast of the Seward Peninsula on the Bering Sea. There in the busy harbor, among the tarnished remnants of a gold rush town, Anne sees examples of the folly of human narcissism. By observing the chief of an ancient Eskimo tribe who is forced to sell trinkets to tourists in order to survive, Anne studies the social mythology of demigods, pathetic symbols of power in a universe beyond human control. The chief is taller and stronger than any of his tribesmen—he belongs to the “born rulers of the earth.” And yet, Anne says, he is nothing more than a clown who ceases to be the king when he does not perform. He is worshipped as an image of royal invincibility. But he is, in fact, the court jester. Narcissistic, arrogant, and domineering, he mistakes his image for reality. Like Charles, Anne implies, he is the plaything of Nature, a “flying fool” deified by man.

Once again, they fly across the Bering Sea to its northeast peninsula and the Sea of Okhotsk. On the tiny Russian island of Karaginskiy, the secular concerns of a scientific and industrial society have obscured the

spiritual aspects of life. This, Anne writes, is another barren land, no less sterile for its civilized modernity. Nonetheless, Anne finds a common bond with these women, whose culture and language are alien to her own. Spreading her photographs of Charlie on the table, Anne becomes connected to them and to “the boy” she left at home. While the Communist Party has replaced the priesthood, the human spirit cannot be crushed. Feelings and relations are the basis of what it means to be human.

Leaving Russia, they follow the chain of islands linking the Kamchatka Peninsula to Japan. The small island of Ketoi, with its little harbor cupped inside green volcanic peaks draped in fog, looks like the idyllic scene in a Japanese print—timelessly tranquil.

Like the skilled writer of a mystery tale, Anne slowly builds toward an overwhelming realization. Both writer and protagonist, ubiquitous surveyor and helpless victim, Anne spins a tale of pursuit by a monstrous Giant—the menacing fog. Her intent is to depict a battle of wills, confrontation between Man and Nature. Slowly the “shimmering unreal world,” too beautiful to be threatening, succumbs to the enveloping fog. As fear creeps over her, Anne tries to keep it away with cold analysis, only to find herself imprisoned within it.

The Japanese stationmaster advises them to turn back, but his power, demonstrated only in words, is impotent against the force of Nature. Charles, her husband, is the true hero, the one who can conquer the Giant. He is the perfect shape of manhood—or is he? Until now, Charles has been the absent, invisible pilot-operator. Suddenly, he moves to center stage. He is the hero, tested to the very edge of the warrior’s courage. Yet, writes Anne, Charles looks like a skeleton, flattened against the wind, a man “gritting his teeth in his lost fight.” His is the very face of death. He, the jester who once made the princes laugh, is silenced by the power of death.

The flight slips further into allegory as Anne confirms her insights among the kind-hearted and provincial inhabitants of the remote islands of Japan. But all symbolic references cohere in her description of the Japanese tea ceremony, an event that does not have a geographic

center. Even the reader though understands that it takes place on the outskirts of a city on one of the larger Japanese islands. Anne leaves the ritual remote from time and space, disconnected from the social realities of life in Japan. The tea garden is an oasis, an aesthetic setting apart from the turmoil of daily routine. If language has expressed the magic, silence is now the harmonizing melody. Words breed meaning, and yet they cannot touch the essential core.

All the people Anne meets on her pilgrimage “home” share one need: to be participants in a human and spiritual community. Anne asks, “What is essential to human life?” and carefully strips humanity of its social and cultural artifacts: language, convention, and technology. “Home” is no longer a physical refuge; it is the stillness at the center of one’s mind, giving rise to self-knowledge and reconciliation. Silence is the alchemy that changes the artifacts of language and culture into the “gold” of beauty and art. Words and symbols, though no more than representations of human experience, are the only means for deriving understanding from the past.

Contrary to Hebrew scripture, Anne does not decry the graven image, the semblance of life through art. It does not presume power; it imbues life with meaning.

Death is the finality that cannot be challenged. But, Anne writes, it does not mean oblivion. Those we love must die, yet aesthetic symbols can re-create our memories and sustain our love. The bridge of words is like a beautifully woven “band of cloth” spanning the space between lovers. And, by implication, so is her book.

Anne cannot return to the home of her childhood. North Haven is forever changed; she cannot know again the joy of seeing her father and the baby wave good-bye. But life, stripped of certainty and magic, still holds room for affirmation. The scars of loss have been healed by art, the “beautiful abyss” between earth and sky. Anne has defied the God of her ancestors and justified the blasphemy of the written word. She has unthroned Charles, crowned Nature and Chance, and has begun to find her long way “home.”

Purgatory

A

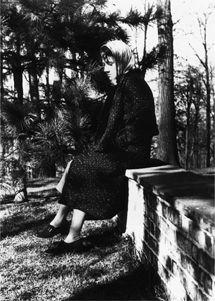

nne prepares for the Hauptmann trial, Englewood, 1935. (Lindbergh Picture Collection, Manuscripts And Archives, Yale University Library)

With rage or despair, cries as of troubled sleep or of a tortured shrillness—they rose in a coil of tumult, along with noises like a slap of beating hands, all fused in a ceaseless flail that churns and frenzies that dark and timeless air like sand through a whirlwind

.—

DANTE

,

The Inferno

,

F

OREHELL

, C

ANTO

3

ANUARY

1933, E

NGLEWOOD

, N

EW

J

ERSEY

T

he New Year resounded with life. The baby was growing fat and strong, and more and more Anne released herself into the moment, feeling “younger and gayer” than she had in the long dark months before. Thoughts of Charlie’s death intruded, but Jon’s presence soothed everything.

While New York sank deeper into the Depression, and the restaurants and hotels were somber and half-empty, Anne and Charles moved in the rarefied circles of the wealthy and the famous, insulated from a country in turmoil. Foreign governments vied to honor them; the giants of industry and commerce pulled them to their side. Face to face with the beautiful, coiffed, and velvet-gloved women of New York society, Anne set aside her “mask.” Her own feelings, so close to the surface, made her self-conscious and vulnerable.

1

They went to Amelia Earhart Putnam’s house for dinner. But it was to be a “prickly” evening. Earhart seemed to look right through her, disdaining Anne’s conventional femininity. Extending her long and gracious hand, Earhart asked coolly, “Have you read

A Room of One’s Own?”

2

It was as if Earhart knew how difficult it was for Anne to break free of Charles. Among female pilots, Anne never earned a reputation as a

true flyer. To this small coterie of women, Anne, who didn’t fly solo, was viewed as an appendage to Charles. Earhart’s question was almost rhetorical.

During the first week in January, Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West arrived in town for their “American tour.” Nicolson, a British foreign officer, a novelist, and a biographer who had recently abandoned his diplomatic career, was feeling middle-aged and depressed. His new career as a journalist and a radio broadcaster was unsatisfying. His wife, Vita, however, a bisexual with enough energy and optimism for both of them, had earned herself a reputation as a novelist. Both had become popular among the British avant-garde as social commentators and literary critics. Their public speeches and radio broadcasts supplemented Nicolson’s uncertain income and Vita Sackville-West’s shrinking family funds.

3