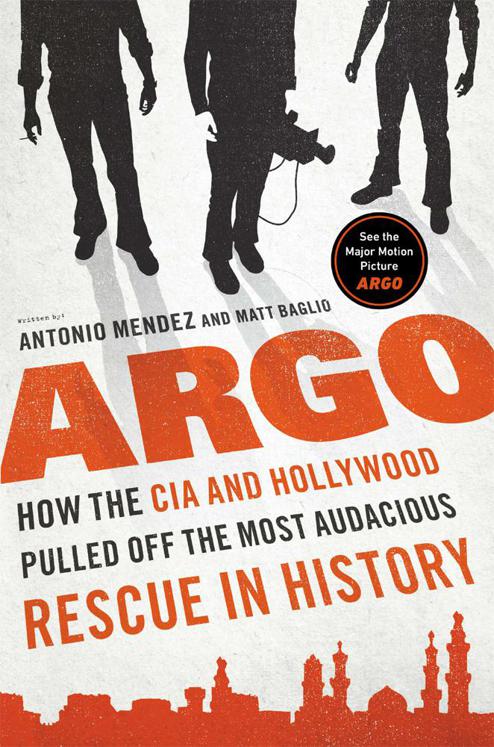

Argo: How the CIA and Hollywood Pulled Off the Most Audacious Rescue in History

Read Argo: How the CIA and Hollywood Pulled Off the Most Audacious Rescue in History Online

Authors: Antonio Mendez,Matt Baglio

Tags: #Canada, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #History & Criticism, #20th Century, #Post-Confederation (1867-), #History & Theory, #General, #United States, #Middle East, #Political Science, #Intelligence & Espionage, #History

ARGO

Also by Antonio J. Mendez

The Master of Disguise

Spy Dust

Also by Matt Baglio

The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist

ARGO

HOW THE

CIA AND HOLLYWOOD

PULLED OFF THE

MOST AUDACIOUS RESCUE IN HISTORY

Antonio J. Mendez

and Matt Baglio

VIKING

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2012 by Viking Penguin,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © Antonio J. Mendez and Matt Baglio, 2012

All rights reserved

All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official positions or views of the CIA or any other U.S. Government agency. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying U.S. Government authentication of information or Agency endorsement of the authors’ views. This material has been reviewed by the CIA to prevent the disclosure of classified information.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mendez, Antonio J.

Argo : how the CIA and Hollywood pulled off the most audacious rescue in history / Antonio J. Mendez and Matt Baglio.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-101-60120-4

1. Iran Hostage Crisis, 1979–1981. 2. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. 3. Canada—Foreign relations—Iran. 4 Iran—Foreign relations—Canada. 5. Mendez, Antonio J. 6. Diplomats—United States—History—20th century. I. Baglio, Matt. II. Title.

E183.8.I55M46 2012

955.05’42--dc23

2012014991

Printed in the United States of America

Set in ITC Galliard Std

Designed by Alissa Amell

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

ALWAYS LEARNING

PEARSON

To Jonna

Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Late that Saturday afternoon I was painting in my studio. Outside, the sun was just beginning to fall behind the hills, casting a long dark shadow that covered the valley like a curtain. I liked the half-light in the room.

“Come Rain or Come Shine” poured from the radio. I often listened to music while I worked. It was almost as important to me as the light. I had installed a fine stereo system and if I painted late enough into Saturday night, I could catch Rob Bamberger’s Hot Jazz Saturday Night on NPR.

I had been painting since my early childhood, and was working as an artist when the CIA hired me in 1965. I still considered myself to be a painter first and a spy second. Painting had always been an outlet for the tensions that came with my job at the Agency. While there were occasional bureaucrats whose antics brought me to the point of wanting to throttle them, if I could get into my studio and pick up a brush then those pent–up hostilities would melt away.

My studio sat perched above the garage, up a steeply angled set of stairs. It was a large room with windows on three sides. The room had diagonal yellow pine floors covered with a variety of oriental carpets and was furnished with a huge white sofa and some

antique pieces that my wife, Karen, had acquired for her interior design business. It was a comfortable space and, most important, it was mine. You needed permission, which I gave pretty freely, to enter. Friends and family knew, however, that when I was in the middle of a project, they should tread lightly.

I had built the studio as I had built the house. Upon returning from a posting overseas in 1974, Karen and I had decided it would be best to raise our three kids away from the grit and crime of Washington, D.C. We’d chosen a forty-acre plot of land in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and after clearing a section of woods, I’d spent the better part of three summers constructing the main house while the family and I lived in a log cabin I had also built. The land had a long history. Antietam Battlefield was just up the road and every now and then we would find Civil War relics—buttons, bullets, breastplates—discarded among the leaves and fallen trees bordering our property.

The painting I was working on that afternoon had been triggered by a phrase associated with my job: “Wolf Rain.” It had the haunted sound of blue, dreary, dank weather, and spoke to the depths of the wooded landscape, just outside my window, on a winter’s night. It conveyed a kind of sorrow that I couldn’t explain, but felt that I could paint.

Working on “Wolf Rain” was one of those things you hope happens in your career as an artist—the painting just emerges from nowhere. Perhaps like a character who shoulders his way into a book to take over the narrative. The figure of the wolf was recognizable only by the eyes—it was a floating image in a rain-soaked forest, and you could sense the anguish in its gaze.

If my painting was going well, my brain would instantly go into

“alpha” mode, the subjective, creative right-brain state where the breakthroughs happen. Einstein said that the definition of genius is not that you are smarter than everyone else, it’s that you’re ready to receive the inspiration. That was the definition of “alpha” for me. I would start the painting session by ridding myself of all the assholes at work and then leap to moments of clarity where I would find solutions to problems that I had never considered before. I would be ready to receive.

It was December 19, 1979, and there was much on my mind. Earlier in the week I had been given a memorandum from the U.S. State Department that contained some startling news. Six American diplomats had escaped from the militant-overrun U.S. embassy in Tehran and were hiding out at the residences of the Canadian ambassador, Ken Taylor, and his senior immigration officer, John Sheardown. The six appeared to be safe for the moment, but there was no guarantee they would remain so; in the wake of the embassy takeover, militants were combing the city looking for any American they could find. The six Americans had been in hiding for almost two months. How much longer could they hold out?

The news of their escape had come as a bit of a surprise to me. I had spent the previous month down at the CIA engrossed in the wider problem. On November 4, a group of Iranian militants had stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and taken more than sixty-six Americans hostage. The militants accused the Americans of “spying” and trying to undermine the country’s nascent Islamic Revolution, all of this while the Iranian government, led by the Ayatollah Khomeini, lent its support.

At the time of the takeover, I was working as the chief of the CIA’s worldwide disguise operations in the Office of Technical

Services (OTS). Over the course of my then fourteen-year career, I had conducted numerous clandestine operations in far-flung places, disguised agents and case officers, and helped to rescue defectors and refugees from behind the Iron Curtain.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, my team and I had been working on preparing the disguises, false documents, and cover stories for the various aliases that any advance team would need in order to infiltrate Iran. Then, in the midst of these preparations, the memo from the State Department arrived.

As I applied a dark glaze across the underpainting of the canvas, it immediately transformed the mood of the work. The piercing eyes of the wolf suddenly came alive like two golden orbs. I stared, transfixed. The image had triggered something. The State Department appeared to be taking a wait-and-see approach with the six Americans, which I found to be problematic. I had recently been to Iran on a covert operation and I knew the dangers firsthand. At any moment they could be discovered. The city was full of eyes, watching, searching. If the six Americans had to run, where would they go? The crowds of thousands of people chanting outside the American embassy in Tehran each day gave no doubt that, if captured, the six would almost certainly be thrown in jail and perhaps even lined up in front of a firing squad. I had always told my team that there are two kinds of exfiltrations: those with hostile pursuit and those without. We couldn’t afford to wait until the six Americans were on the run. It would be almost impossible to get them out then.

My son Ian walked into the studio. “What’s up?” he asked. He walked over to the painting and scrutinized it as only the seventeen-year-old son of the artist could. “Nice, Dad,” he pronounced,

stepping back to get a better perspective. “But it needs more blue.” He’d barely noticed the eyes of the wolf.