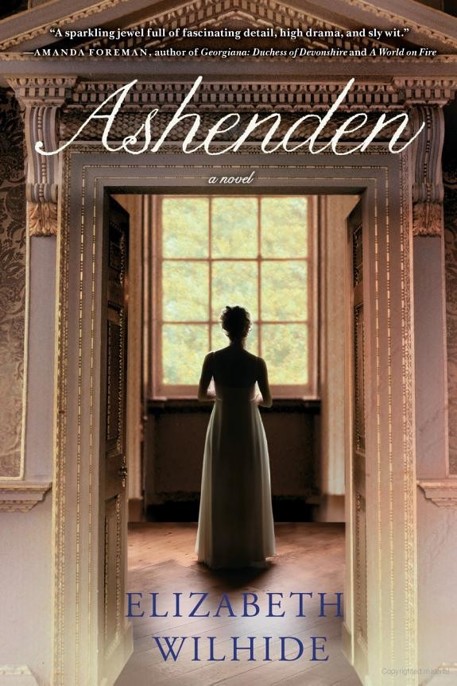

Ashenden

Authors: Elizabeth Wilhide

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #Cultural Heritage, #Contemporary Fiction, #Literary, #Historical Fiction

Chapter 1: The Cuckoo’s Egg: 2010

Chapter 3: A Book of Ceilings: 1796

Chapter 6: The Janus Cup: 1889

Chapter 7: The Boating Party: 1909

Chapter 8: The Photograph: 1916

Chapter 9: The Treasure Hunt: 1929

Chapter 10: Love in Bloom: 1938

Chapter 12: The Waiting Room: 1951

Chapter 13: The Interview: 1966

Chapter 15: The Winter Season: 2010

Chapter 16: All You Want (Tonight): 2010

Thank you for purchasing this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

In memory of my mother

The Cuckoo’s Egg: 2010

W

inter has been hard on the house, the bitter cold eating into the honey-colored stonework, causing portions of the façade to crumble and flake away. Even in the external areas that are less exposed—under overhangs, for example—where the weeks of severe frost have been prevented from doing their worst, fresh staining has appeared in ugly blotches that bloom like malevolent flowers of decay.

Ashenden Park, built towards the end of the eighteenth century, and one of the finest late Palladian houses in the country according to those who make it their business to judge such things, was once surrounded by thousands of acres. Over the years the estate has shrunk to grounds of under a few hundred, which is nevertheless more than enough to provide an uninterrupted view from all sides.

Look around. It is as if the house were an island domain in a sea of green. In front, land slopes away, then rises to a gentle hill dotted with stands of trees and grazed by deer; behind, terraces descend more abruptly to the river, the modern world nowhere in evidence. The principal block, like the two smaller pavilions that flank it, is crowned with a pediment on the main elevation. Its centerpiece, and the focus of the symmetry of threes and fives and sevens, is a recessed columned loggia that soars from the first floor to the roof. At the lower story a continuous wall topped with a balustrade links the buildings together and makes elegant sense of it all. From a distance,

as you come up the drive, for instance, the crisp lines of the architecture appear intact and it is possible to appreciate the clarity of the design more than two centuries since it sprang from a drawing into life, from a mind into being.

Look again. Up close the deterioration is brutal and alarming. Stone teeth missing under the roofline, rotten sills, the dull blank eyes of windows. Another winter as severe as this, the rot will find its way indoors and there will be serious trouble. Already the roof is leaking and the background heat that has been maintained in the principal rooms is barely enough to ward off the damp.

The house is much smaller than a palace, smaller too than many others of its type, yet much larger than most people today would recognize as a home. How many rooms? It depends on how you count them. About two dozen in the main block, give or take, not including hallways, landings, staircases, of which there are many. The side pavilions, once service quarters, are houses in themselves. Altogether it is a mansion, perhaps, but here is a trick of the architecture: a mansion that feels both generous and human-scaled. Were you to see it from above, from the flight path to Heathrow under which it lies, you might imagine yourself picking it up and placing it in the palm of your hand for safekeeping.

The house contains time. Its walls hold stories. Births and deaths, comings and goings, people and events passing through. Some of the occupants of the Park (and not all its occupants have been owners) have treated it well; others have been criminally careless. For now, however, it lies suspended in a kind of emptiness, as if it has fallen asleep or someone has put it under a spell. This silence won’t last: can’t last. Something will have to be done.

* * *

Charlie Minton, fifty-seven years old, twice married, father of one, woke up and for a moment didn’t know where he was. It was a familiar feeling: over the years he’d woken up in boardinghouses, tents, three-, four-, and five-star hotels, shacks, on the backseats of cars and airport floors, in Beirut, Tokyo, New Orleans, Rio, and Pretoria,

and had had the same momentary feeling of dislocation. It was part and parcel of the itinerant, unsettled life he had once chosen for himself and sometimes still hankered after. Now, he thought, this gray light could only be England, and as he came more fully into the day, something even worse occurred to him, which was that he was at Ashenden Park. More specifically, he was lying in bed in one of the spare rooms in the south pavilion, part of the house converted by his aunt and uncle over thirty years ago for their retirement.

He burrowed under the duvet, but any hopes that his mind would drift back to sleep and leave him in peace for another five minutes came to nothing. How could it, when every morning for the past two weeks the same dead weight had landed on him as soon as he had opened his eyes?

Over a fortnight ago, a February evening, he had been sitting at his worktable at home in the apartment on the Lower East Side he shared with his second wife, Rachel, correcting the proofs of a catalog to accompany a retrospective exhibition of his photographs. It was the kind of judgment that needed daylight, and he had moved away from the deceptive warmth of the Anglepoise to stare out of the window at snow flurries blown upwards and sideways in the sodium glare. He was thinking that he didn’t much like the word “retrospective”—it reminded him how old he was—when the phone had rung. The dog, snoozing in her basket, raised her head.

It was Rachel’s night at the Sita Center and she would be calling to say that she had yoga brain and should she pick up a takeout or was there something in the fridge. But as he reached for the handset, snug in its cradle like a papoose, he’d thought it was odd she was calling on the landline. Rachel always called him on his cell.

It hadn’t been Rachel and it had only been when he’d picked up the phone that he’d noticed the red light was blinking.

Down under the duvet, clinging to his body heat on a cold, damp English morning, Charlie remembered his wife coming through the door of their apartment that February evening in New York, dumping her bag of yoga kit, snowflake stars melting on the little black ankle boots he’d given her for Christmas. Greeting the ecstatic dog,

whose claws skittered across the waxed floorboards. Then taking a look at his face and asking what was the matter.

For a moment he had considered not saying anything at all. Pretending nothing had happened. Then he told her that his sister had just called with the news that Reggie was dead.

“Your aunt Reggie?”

He nodded.

“Oh, I’m so sorry, honey.” She came across the room to give him a hug and he could smell sandalwood in her hair. “That’s too bad.”

At this point anyone else would have said that his aunt had been over ninety and had had a good, long life. But Rachel never said the obvious thing, which was one of the reasons he loved her.

“When did it happen?”

“Around noon their time. Ros was pretty upset. She’s been trying to get hold of me all day.” Ros was his sister.

“Didn’t she try your cell?”

“Repeatedly. Bloody useless network.”

Rachel rubbed his arm. “You planning on going over for the funeral?”

Before he could answer, he had to tell her the rest of it, knowing that would mean there was no further retreat from reality. “Reggie’s left us the house. Me and Ros.”

Rachel drew back. “That big old place?”

“Ashenden Park.”

Ashenden Park. An image of its tawny stonework, its severe classical symmetries, formed itself in his mind. His uncle Hugo— his mother’s brother—had bought the house just after the war and, together with his wife, Reggie, had saved it from what would have been almost certain destruction. The two of them had been devoted to one another and the house they had painstakingly restored but they had never had children of their own.

“I thought it was going to be donated to the country or something.”

“To the National Trust.” His breath constricted in his chest, and he felt the same sensation he’d had when he’d heard the news

twenty minutes before: that of opening a door and stepping into space. Falling down, down, down, his feet scrabbling for a floor that wasn’t there. “That’s what we all thought.”

“Is Ros sure?”

“She rang Reggie’s solicitor this afternoon and he told her. We’ve inherited the house and whatever’s left of the trust Hugo set up for her. I’ll have to get over there straightaway.”

Rachel’s face registered internal adjustments, shifts of perspective. Yet, and this was another reason why he loved her, she did not rush to offer her opinion or second-guess his own. She held back. Only this late in life had he come to understand the paradox of true intimacy: that it depended on this type of respect.

He said, “Whatever happens, it’s not going to be quick. I’ll have to cancel my seminars at Parsons. Take a leave of absence.”

“The exhibition?”

He shrugged. “Let’s eat. We’ll talk after.”

* * *

Now, two weeks later, on this soggy gray morning at Ashenden Park, lying in the hollow of the mattress, the slightest movement accompanied by the creaking of the tarnished brass bedstead, the percussion of its springs, Charlie thought about what a good buy those little black ankle boots had been and how much he would like to see Rachel wearing them this very minute. He badly missed his wife.

In his first marriage, Charlie had experimented with similarity, shared interests, and things in common. He had since come to the conclusion that opposites worked better. People always imagined that opposites clashed, but in his experience similarities did, each vying for the same piece of ground. Opposites didn’t have to mean conflict, wars of attrition, any more than they had to attract; sometimes, they made for smooth-running train tracks.

He and Rachel had met eight years ago at a Parsons fund-raiser: his seminars were beginning to be popular with the students and there was a rumor that he might be offered tenure; she was a graduate of the textile department, a “funky knitter” according to a colleague

who’d noticed where Charlie’s eyes were straying, and “the daughter of Jacob Gronert, one of our foremost benefactors,” according to a glad-hander from faculty administration who had eventually introduced them. She hadn’t looked like a knitter, more like the answer to hopes he hadn’t entertained for years. A week later they first slept together; three months after that (which was two months after the attack on the Twin Towers), she had moved into the Lower East Side apartment he’d rented ever since the days when no cabs would go there. The following summer they were married.

For the first time ever Charlie discovered that it was possible to enjoy domestic life, to look forward to seeing someone else’s toothbrush in the bathroom morning after morning. The same someone’s toothbrush.

He bagged up a lot of his old stuff and threw it away. Together they bought new stuff. They sanded the stained floorboards and got a puppy. He was offered tenure, she exhibited her pieces here and there in SoHo galleries, then started up a blog called “Wool and Water” just as the craft revival was beginning to break, which led to a shop called Wool and Water in Tribeca, where she sold Peruvian hand-dyed yarn, skeins of fair-trade cashmere, and ran evening classes for the stitch-and-bitch brigade. Which led to a book, also called

Wool and Water,

with an explanatory subtitle for those unfamiliar with the

Alice in Wonderland

reference. (Even now some people came through the door of the shop expecting to buy bottles of Evian.) It was around this time that her parents, who hadn’t approved of her marrying him, warmed up a little and her father suggested advancing her the capital to expand the shop into a chain. When Rachel turned her father down, Charlie couldn’t have been prouder of her determination to own her own life.

A twenty-five-, thirty-five-, forty-five-year-old Charlie, riding along in the backseat of some clapped-out township taxi with his beaten-up Nikon F while the driver casually leaned an assault rifle out the window, or drinking in the bar of a scuzzy Macedonian hotel with stringers, indiscreet diplomats, and local mafia, or failing to show up on the second (and last) occasion when one of

his photographs won a press award because he was sweating in a Mexican jail near the border, would not have recognized this fifty-seven-year-old Charlie, this home improver, wife lover, dog owner. But when he looked back on those exploits now, polished by many retellings, he recognized they were little more than approximations of the truth, which edited out the boredom, fear, and bad behavior that had led to them or been their direct consequence. They didn’t even correspond to the occasions when he had taken his best photographs. Such was the benefit of hindsight and, however late in life, a good marriage.