Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (20 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

Tyrrell had brought two associates, Miles Forrest who had murdered before, and Tyrrell’s horse-keeper, a thug called John Dighton. Having gained entrance to the princes’ room, Tyrrell sent Forrest and Dighton inside at about midnight. They rushed in, and as one wrapped the boys in their bedcoverings, holding them down, the other stuffed pillows into their mouths, suffocating them until they died.

The murder of Edward and his brother

The murder of Edward and his brotherNow the murderers called Tyrrell into the room to witness the fact that both the uncrowned Edward V and his brother Richard Duke of York were dead. Tyrrell then arranged their secret burial.

13

What of the murderers? Forrest was appointed Keeper of the Wardrobe (the spending department) of King Richard’s mother. Tyrrell was appointed Master of the King’s Henchmen

(squires). Amazingly, he was granted a pardon by Henry VII, but was later executed for supporting a failed claimant to the throne.

Of course, Richard’s guilt is not certain. The boys were not just a threat to Richard’s crown, they were also a threat to Buckingham who aspired to the crown and to Henry Tudor who had some hopes. As to Buckingham, he needed their deaths more than Richard did. Richard had already managed to seize the crown with the boys alive and he would gain little from their deaths other than security. If Richard died, Buckingham would struggle to obtain the crown whilst the boys lived.

But despite Richard’s loyalty to Edward IV and his dutiful behaviour in all matters until he saw the possibility of the crown in Northampton, he remains the likeliest, if not the certain, person responsible for the murder of Edward V.

13 In 1674, the skeletons of two children were found under a staircase during renovation work to the White Tower. They were re-buried in Westminster Abbey.

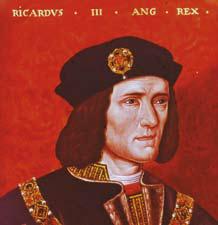

RICHARD III

26 June 1483 – 22 August 1485

King of England at last, Richard had a number of advantages and a number of disadvantages. On the plus side, he was the brother of the previous king (or uncle if young Edward was counted), he was from the senior House of Clarence/York, he was of good age for a king, he had an impressive record of military leadership, he was popular in the country and his wife had already produced a son.

On the minus side, he was a usurper, he had apparently organised the murder of the true heir, he had ordered the execution of nobles without trial, and apart from Buckingham he had no major allies.

Yet one problem can always override many advantages. In the end, it would be the deaths of three children that united Richard’s enemies and lost him support.

Having accepted the throne by acceding to Parliament’s petition engineered by Buckingham, and having in all likelihood disposed of the rightful heir, Richard was comfortable in his position. A usurper on taking the throne certainly, but after the deaths of the two princes he was actually the first adult male in line. The only possible better claim was that of the son of Richard’s older brother, Clarence. But that son was an eight-year-old mentally retarded child whose father had been attainted (convicted of treason by parliament and without trial). The attainder also barred issue

– although attainder could be reversed. His sister Margaret was also barred by the attainder.

Now Richard travelled the country on a royal progress, impressing his subjects and receiving their genuine approval. But in time, news of the murder of the two princes galvanised the Woodvilles and the Lancastrians. However, their candidates for the crown had all been killed; they needed a new one who could be supported by both factions.

Edward IV’s two sons had been murdered and a third had died in infancy. He also had seven daughters, and five of them were still alive. The best choice was the oldest, Elizabeth of York, and she was unmarried. Certainly there was little chance of her being accepted as queen to rule alone. Yet she carried the royal blood of the House of York, and so would her son. If a suitable husband could be found, each would improve the other’s position.

When Henry VI and his son, Prince Edward, were killed, it meant that no legitimate issue of Henry IV, V and VI were still alive. That was really the end of the House of Lancaster. What of the secondary illegitimate Lancaster line through John of Gaunt’s marriage to Katherine Swynford? Their grandson and heir, John Beaufort, had left a daughter Lady Margaret Beaufort as his sole heiress, and she had married Edmund Tudor, the son of Owen Tudor and Queen Catherine (the widow of Henry V).

The son of Lady Margaret Beaufort and Edmund Tudor was Henry Tudor – and he was as good as was available for a Lancastrian heir. Henry was 27 years old and safe in Brittany, having been smuggled there by his uncle Jasper Tudor after the Battle of Tewkesbury.

Next came a major development – Buckingham, Richard’s main ally, changed sides. An agreement was made between Buckingham, the Woodvilles and Henry Tudor. Henry promised to marry Elizabeth of York, and Buckingham agreed to support Henry’s claim to the throne. The Duke of Brittany would supply the finance and the army, and they would invade England in October. Why did Buckingham change sides? Very possibly he was scheming to become king when Richard was dead.

But too many people were involved and too many knew of the plot. Richard found out, and he assembled an army to defend his crown.

Buckingham was to raise forces on the mainland, but incessant torrential rain made travel difficult and many did not arrive at the rallying points. Most of those who did arrive soon left, and Buckingham fell into Richard’s hands and was executed. Richard then marched west, and the Woodville forces scattered in disarray. Henry Tudor’s fleet with 5,000 men on board was caught in a storm, and the few vessels that came near the English shore abandoned the venture and returned to Brittany. It had been a complete farce.

Richard was more secure than ever. Then came the disastrous death of another child. Richard’s only son, 10-year-old Edward Prince of Wales, died after a short illness. Queen Anne (one of Warwick’s daughters did become queen) had not given birth for ten years, and there would clearly be no child to replace Edward.

Now the succession was not assured. After years of civil war, the country yearned for an automatic and peaceful change of monarchs – it was one of the things that Richard had brought to the throne. He needed to nominate a successor. Clarence’s son and daughter were not options, so Richard selected another nephew, John de la Pole Earl of Lincoln, the son of Richard’s sister Elizabeth and her husband the Duke of Suffolk. Lincoln was, in law, next in line; nevertheless, Richard’s position had been seriously harmed.

Of course the real danger was the fact that Henry Tudor was still at liberty. Richard’s first move was to make a deal with Brittany, supplying them with archers in return for a promise that they would take Henry Tudor into custody. Then Richard offered the Treasurer of Brittany (the effective ruler during the Duke’s mental illness) the revenues of the earldom of Richmond if he would hand Henry over. Somehow, Henry, who had adopted his father’s title of Earl of Richmond (although titles were not inherited without the King’s consent), discovered the offer, and he escaped to the court of the King of France.

For both Henry and Richard, it was now time to settle the issue. In December 1484, Richard was almost pleased to learn that Henry was planning to invade in the following summer.

Henry Tudor landed with his army at Milford Haven in southwest Wales on 7th August 1485. His 2,000 soldiers were all French convicts who had been promised a pardon if they fought for Henry. He also brought his uncle Jasper Tudor, plus the Earl of Oxford and very few others. They should have had no chance.

As Henry marched through Wales, thousands joined his army, all eager to fight for a Welsh-named claimant to the throne, although Henry and his parents were born in England and just one of his grandparents was Welsh. When Henry moved into England, his army’s numbers continued to grow as he neared Richard’s fortress base in Nottingham.

Richard prepared for battle. Then, while he was still gathering his forces, he was hit by treachery. Lord Stanley had been an ally of Edward IV, but when Warwick invaded in support of Henry VI, Stanley changed sides. He was forgiven when Edward regained power. After Edward’s death, Stanley backed Richard, only to join the Hastings group who switched to the Woodville side. Although arrested, Stanley was again forgiven. He supported Richard once more, yet he would be the first to defect if he thought that the other side was likely to be victorious. This time there was an added motivation, for Stanley had married Lady Margaret Beaufort, the widowed mother of Henry Tudor. Now Stanley refused to bring his force of 3,000 men to join Richard, even though Richard had taken the precaution of holding one of Stanley’s sons as hostage.

Preparing to move out to battle, having already lost Stanley’s men and having lost to Henry the Welsh contingent he was expecting, Richard heard that Henry was heading for London. Richard had to act, and he left Nottingham at the head of 10,000 men; still larger than Henry’s forces.

The two armies approached each other near Watling Street, the road to the capital. Here, on Redmore Plain (later renamed Bosworth Field), they took their positions, Richard’s army being better placed on the 400 foot high Ambien Hill.

Richard sent a message to Lord Stanley, warning him that failure to join the King’s army would result in the execution of his son. Stanley replied saying that he could afford the loss as he had other sons; but Richard did not carry out his threat. Yet Lord Stanley did not ride to join his stepson Henry’s army. Instead he kept his men to one side of the battle, with his brother, Sir William Stanley, keeping his men to the other side. Both of them were waiting to see who was the certain winner before riding to support the victor.

Henry’s army advanced under the command of the Earl of Oxford. Having no experience of warfare, Henry remained at the rear. As Henry’s men reached Ambien Hill, part of Richard’s forces led by the Duke of Norfolk ran down the slope to meet them. But Norfolk was slain, and his troops began to retreat.

Then Richard ordered the Earl of Northumberland to move forward with his 3,000 soldiers to engage Henry’s advancing men. Northumberland refused, saying unconvincingly that he needed to stay at the rear in case of an attack by Lord Stanley.

All of a sudden, Richard’s numerical advantage had gone. His senior nobles told him to flee, but Richard rejected their advice. He decided to risk all and charge with his remaining loyal knights and squires. Richard led eighty of them, storming down the hill. He knew that killing Henry was now the only way to survive. So Richard rode with his supporters in a wild attack around the right-hand side of the battle, circling the fighting armies and galloping towards Henry, who was waiting behind his army.

Having reached the soldiers surrounding Henry Tudor, Richard and his companions fought their way forward. Slowly, they edged nearer their target, but their numbers were reduced as they advanced. Now Sir William Stanley knew what to do to be sure of ending up on the winning side, and he rode with his men to attack Richard’s small group from the rear.

Eventually, King Richard, having got as near to Henry Tudor as slaying his standard bearer, was isolated and surrounded by the enemy. Richard continued to wield his axe in all directions, shouting out “Treason!”, “Treason!”, until he was cut down and butchered; so joining Harold as the two English monarchs to die in battle.

Not remembered as such because of the antipathy of Tudor historians and playwrights, Richard died more gallantly than any other English king before or since.

Killed by traitors, Richard’s naked body was thrown on a horse and taken to Leicester, where it lay exposed for two days before being buried without ceremony in a friary. It is said that years later, his bones were dug up and thrown into the River Soar. A cruel fate for a murdered king who had probably procured the murder of a king himself.

HENRY VII

22 August 1485 – 21 April 1509