Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (4 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

Now that he was king, Harold was faced with two threats: King Harald III of Norway (known as Harald Hardraada) and Duke William of Normandy.

It all started with Harold’s brother Tostig, who was still living in exile. When he heard that Harold had taken the crown, Tostig, eager for revenge, wasted no time in encouraging Harald Hardraada to invade England. They set sail, with Harald Hardraada demanding the throne of England under the treaty between his predecessor Magnus and Harthacanute. The claim was that Magnus became entitled to the English crown when Harthacanute died childless, and Harald Hardraada was the inheritor of his nephew and predecessor Magnus’s rights.

Harold immediately rode north to deal with the mightiest warlord in Europe (Hardraada meaning ‘a hard ruler’), who had landed with an army of 15,000 men carried across the sea in 300 ships. In a brilliant victory, Harold defeated the invaders at Stamford Bridge near York on 25th September 1066, killing Tostig, Hardraada and the majority of his army. It needed only 30 ships to carry the survivors back to Norway.

William was next. Born in 1028, Duke William of Normandy was the illegitimate son of Duke Robert of Normandy and Herleve, the daughter of a tanner (a maker of leather). As a result, William grew up in Normandy as ‘William the Bastard’. However, he was Duke Robert’s only son, so despite his illegitimacy William succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy as decreed in his father’s will.

Again, Edward the Confessor’s mother, Emma of Normandy, provided the link. She was the daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy, William’s great-grandfather. It made William the second cousin once removed of Edward the Confessor – and that was one of William’s claims to the English throne. Sensibly, he did not overplay that hand, because relying on heredity would be admitting that Edgar the Atheling, the son of the Exile, should be king. Edgar was, after all, the grandson of Edward’s half-brother, Edmund Ironside.

William’s main claim to the throne was that Edward had promised him the succession in gratitude for the years of sanctuary in Normandy. This is rather doubtful as William was only 14 years old when Edward left Normandy, and Edward must have known that William’s illegitimacy would be an issue for the Anglo-Saxon Church.

Nobody in England was listening; Harold had already been crowned. William was incensed. He complained bitterly to the Pope that Harold had sworn to acknowledge him as Edward’s heir. William said that this had happened in 1064, when Harold had been sent to Normandy, supposedly to confirm Edward’s promise of the succession. Harold’s ship was blown off course, and he landed in Ponthieu where he was seized and held for ransom. William secured Harold’s release, and in return Harold is said to have sworn on oath that he would accept William as the next king of England. As with William’s other contentions, this Norman justification for the invasion sounds rather contrived. Probably William felt that if someone with no right at all was going to be king, it might as well be him.

Harold’s response was to say that Edward had nominated him as the next king, it had been confirmed by the Witenagemot, and that was an end to the matter. William was not impressed. He knew very well that the Godwines had been Edward’s main opponents for years, responsible for the murder of Edward’s brother Alfred, and continually fomenting revolts. Harold was hardly the man Edward would promise the throne to on his deathbed; at least, not willingly. Yet, in Harold’s favour, he was of the royal house of Wessex, he was Edward’s brother-inlaw, and although probably no one knew it he was Edward’s eighth cousin three times removed (see page 6). More to the point, there had been no adult Anglo-Saxon alternative.

Critically, King Henry I of France had died, leaving as his successor the eight-year-old King Philip. With France having an infant king and being governed by co-regents, one of whom was William’s father-in-law, the French threat to Normandy was much diminished, so William felt safe in leaving Normandy with his forces to seize the English crown. Having waited for the Pope’s approval, that is exactly what William did.

Three days after the Battle of Stamford Bridge, William’s army landed in Sussex and took up position near Hastings. By now Harold was back in London, celebrating his victory over Harold Hardraada. When he was given the news of William’s landing, Harold wasted no time. He was eager for battle. Harold set about raising a new army, and then he marched south to confront the invader.

The two armies were each about 7,000 men strong. Harold’s forces were nearly all on foot as although senior Anglo-Saxons rode to battle, they generally dismounted to fight. They were armed with swords, axes and javelins. Standing ten ranks deep on firm ground on the summit of Senlac Hill, their flanks were protected by marshland on either side. The Normans were a combination of mounted knights, infantry and archers. William commanded from the centre with his Norman knights. They were supported by Flemish and French to the right and Bretons to the left.

First, William’s archers let fly, but to little effect. Then, William told his infantry to advance. As the invaders moved forward, the Anglo-Saxons hurled their javelins at William’s left flank. The Bretons’ advance was halted with scores of them killed, and the survivors turned and ran away downhill. Seeing the opportunity for easy killing, many of the Anglo-Saxons broke from their line and chased the Bretons as they fled.

William countered by directing some of his knights to attack the Anglo-Saxons who had run ahead and become detached from their main army. The Norman knights now trapped and slaughtered all the pursuing Anglo-Saxons.

With the momentum in his favour, William sent a contingent of knights forward. They reached Harold’s men, but the AngloSaxon line held fast, and the Normans fell back in disarray. Again, many Anglo-Saxons raced after the retreating knights, and when those pursuers were separated from their main force, William attacked with the rest of his knights. Just as before, the pursuing Anglo-Saxons, all on foot, were encircled and killed.

Naturally the Normans later claimed that both retreats had been tactical moves, intended to draw the Anglo-Saxons forward so that the cavalry could destroy them. Perhaps.

Despite the reverses, Harold was not finished. He commanded his men to return to the original defensive formation. However, having suffered heavy losses, the line was much shorter. As a result, there was firm land between the flanks and the marshland. Protection of the sides had gone, and William had seen it.

His confidence soaring, William ordered his infantry and cavalry to charge. The Anglo-Saxon line still held, but William’s knights could now attack the flanks of Harold’s army from the firm ground on either side, and they did so to deadly effect. Yet, although Harold’s position had deteriorated, the issue was still in doubt as the Anglo-Saxons protected themselves with their large shields, desperate to hold out until nightfall.

The battle had lasted a very long time, over nine hours. In half an hour it would be dark, and then both armies would have to withdraw. They would only be able to resume fighting at dawn.

At this crucial stage, it was vital for the Normans to use all their available resources in a massive effort to gain victory, as Harold could expect to receive reinforcements by morning. The Normans had one resource that had been largely unemployed – their archers standing to the rear, hardly letting fly at all for fear of hitting their own men. William rode back and shouted at his archers, ordering them to shoot high into the air so that their arrows and bolts would fly over the Norman attackers and come down on the enemy. This was a strategy he probably adopted not in the expectation of causing many deaths, but rather to force the Anglo-Saxons to raise their shields above their heads to protect themselves from the falling arrows, so weakening the wall of shields the Norman infantry and horsemen were struggling to breach.

The archers took hold of their crossbows and aimed high. Within seconds, a shower of arrows and bolts rained down on the Anglo-Saxons.

One arrow changed the course of English history. Puzzled at the strange sound overhead, Harold instinctively looked to the sky, and at that moment, as he gazed upwards, an arrow hurtling to the ground struck him in the eye.

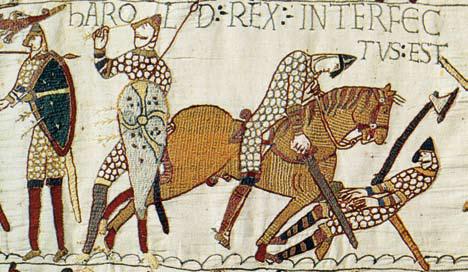

The death of Harold

The death of HaroldNow the Normans broke through the disintegrating wall of shields. Already mortally wounded, Harold was hacked down beneath his standard of the golden dragon of Wessex, his two surviving brothers having already fallen. After a final stand by Harold’s housecarls, the remaining Anglo-Saxons, beaten and leaderless, fled. A number of Norman knights pursued them, but as they rode through a gully known as the Malfosse in the near-dark, they were ambushed and many Normans were killed before the Anglo-Saxons ran off. Then Duke William arrived and met up with the surviving fifty Norman knights. As Count Eustace of Boulogne was explaining what had happened, suddenly an Anglo-Saxon lying on the ground feigning death leapt to his feet intent on killing William. First he struck Eustace between the shoulder blades so forcefully that blood spurted from Eustace’s nose and mouth; then, turning to William, the Anglo-Saxon raised his sword – but he was killed before he could strike.

It was over, and somewhere there was a Norman who did not even know that he had killed the King of England.

Yet it was not the end of the Godwines, because far from the battlefield some of them lived on. Two of Harold’s sons and his daughter, Gytha, managed to escape. They fled to the court of King Sweyn Estridsson of Denmark. King Sweyn was the son of Ulf and Estrith (Canute’s sister), who were the children’s great-uncle and great-aunt. Gytha later married Grand Prince Vladimir Monomakh of Kievan Rus, a state (covering much of present-day western Russia) that had been established by Norse settlers. In time, the Godwine blood would flow through the five sonsof Gytha and Vladimir into several European royal families, and as we shall see, through the marriages of Edward II and Edward III, back to the English Royal Family.

The last Anglo-Saxon King of England had perished; nevertheless his descendants would wear the crown.

WILLIAM I

25 December 1066 – 9 September 1087

William marched into London with his conquering army. He was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066 by Ealdred the Archbishop of York. The Anglo-Saxon church was in no position to object to the crowning of a bastard. Of course, William was not claiming the crown by inheritance, he was claiming it by conquest. Perhaps illegitimacy was not such a problem after all. Anyway, rather than take responsibility, Ealdred asked the assembled crowd if it was their wish that William should be crowned king. Very wisely, no one objected.

The Conqueror and his compatriots were not really French. They were actually descendants of Viking marauders. In 911, after the Vikings had attacked Paris, French King Charles the Simple allowed a group of Vikings under the leadership of Rollo to settle in northern France on condition that they would protect the coast from future Viking invaders. The settlers were called the Northmen (in Old French:

Normanz

), and their land was known as Normandy, which later included the Channel Islands (today in French:

Les Isles

FAMILY OF WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR

William of the Longsword

Richard I

Duke of Normandy

(2) (1)

CANUTE========Emma=======ETHELRED (r. 1016-35) Queen of England (r. 978-1016)

HARTHACANUTE Gunhilda (r. 1040-42) Queen of Germany EDWARD Goda Alfred THE

(r. 1042-1066) Richard II Duke of Normandy

Richard III Robert I Duke of Duke of

Normandy Normandy

ALFRED THE GREAT

whose daughter Elthrith had

married Baldwin II Count of Flanders

Anglo-Normandes

). Rollo’s grandson Richard became the first Duke of Normandy, and Duke Richard’s great-grandson was William.

Having succeeded to the dukedom of Normandy at the age of seven, William was lucky to survive to adulthood. Many senior Normans thought that they had a better right to rule than a bastard. One of them decided to do something about it. In the depth of the night in the castle-keep at Vaudreuil, a man crept into the room where William, still a young child, was fast asleep. Drawing his dagger, the man reached out, stabbed the sleeping child repeatedly and then ran off. However, the assailant had made a mistake; in the dark he had murdered the boy lying next to William. After that, William was more heavily guarded.