Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (3 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

“As Alfred and his men approached the town of Guildford in Surrey, thirty miles south-west of London, they were met by the powerful Earl Godwine of Wessex, who professed loyalty to the young prince and procured lodgings for him and his men in the town. The next morning, Godwine said to Alfred: “I will safely and securely conduct you to London, where the great men of the kingdom are awaiting your coming, that they may raise you to the throne.” … Then the Earl led the Prince and his men over the hill of Guildown… Showing the Prince the magnificent panorama from the hill both to the north and to the south, he said: “Look around on the right hand and on the left, and behold what a realm will be subject to your dominion.” Alfred then gave thanks to God and promised that if he should ever be crowned king, he would institute such laws as would be pleasing and acceptable to God and men. At that moment, however, he was seized and bound, together with all his men. Nine-tenths of them were then murdered. And since the remaining tenth was still so numerous, they, too, were decimated

2

. Alfred was tied to a horse and then conveyed by boat to the monastery of Ely. As the boat reached land, his eyes were put out. For a while he was looked after by the monks, who were fond of him, but soon after he died…”

Why did Godwine not kill Alfred straight away? Possibly he wished to take power by having the only Anglo-Saxon claimant to the throne in England in a feeble condition and under his control. If so, his plan failed; he would have to think again.

Across the North Sea, Harthacanute signed a peace treaty with Magnus under which each kept his kingdom and promised that if he died childless, the other would be his successor. Now Harthacanute could sail for England. He expected his half-brother to resist, but a civil war was avoided when Harold Harefoot conveniently died. Harthacanute returned as undisputed king.

2 In the 1920s, the remains of several hundred Norman soldiers were found to the west of Guildford. They were bound and had been executed. The grave was dated to c.1040.

Once in England, Harthacanute’s thoughts turned to the succession. He was unmarried and therefore had no legitimate children. So he invited Prince Edward, his half-brother (Emma was the mother of both), to return from Normandy and join the court as the appointed heir. Edward did so, but heirs can be impatient.

A few months later, on 8th June 1042, King Harthacanute was the guest of honour at the wedding feast in Lambeth near London given by Lord Osgod Clapa on the marriage of his daughter Gytha to Tofig Pruda (‘Tofig the Proud’). The King was in good spirits, drinking with the bride and groom and mixing with the guests. It was all very joyous. Barely noticed, an attendant walked over to Harthacanute and refilled his goblet. Continuing his conversation, Harthacanute took another swig. Suddenly, the King’s eyes opened wide into a stare, he suffered a violent convulsion, staggered forward and fell face-down to the ground. It was some time before Harthacanute regained consciousness. He was carried away, unable to speak, dying a few hours later. Perhaps it was a stroke, but more likely it was poison. Who was the culprit: Edward or Godwine? We will never know. The only clue is that, possibly for other reasons – possibly not, once he was king, Edward sent Osgod Clapa into exile. Did he know too much?

So, the first three kings of England all became victims of the curse. Canute survived an attempt to kill him, Harthacanute was murdered and the third (Edward, whose reign follows) survived an attempt to kill him. As we shall see, the survival ratio would deteriorate for future monarchs.

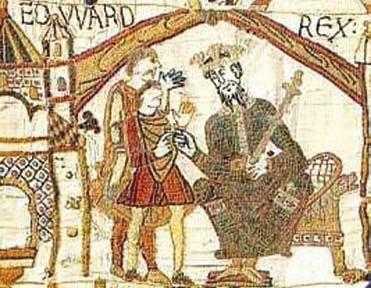

EDWARD THE CONFESSOR

8 June 1042 – 5 January 1066

With Harthacanute dead, in 1042 an Anglo-Saxon from the line of the kings of Wessex took the throne as ‘

Eadwerd Englalandes cyncg

’. Descendant of Alfred the Great, son of King Ethelred and of Emma of Normandy, Edward was the first ‘English’ King of England. He was a tall handsome man, dignified and strong-minded, but like so many English kings he had a terrible temper.

Emma must have been a remarkable woman. She was the wife of two kings (Ethelred and Canute) and the mother of two kings (Harthacanute and Edward). Remarkable or not, after his coronation Edward seized all his mother’s lands and possessions as punishment for favouring her other son, Harthacanute; or perhaps the letter inviting Edward and Alfred to return to England was not a forgery after all. Anyway, another person was much more of a problem. Edward was very wary of Earl Godwine of Wessex, the most powerful man in the kingdom, whose support Edward needed if he wanted

THE GODWINES

Sweyne Tostig Gyrth Gunhilda Aelgifu Leofwine Wulnoth

*Edith~~~~HAROLD===Aldith Edith====EDWARD Swannesha THE CONFESSOR

Godwine Edmund Magnus Gunhild Gytha Harold Ulf

* Although not a Christian marriage, the children were treated as legitimate

to keep the crown. He received that support, but it came at a price. It included creating the Earl’s eldest son, Sweyne, an earl, and marrying Earl Godwine’s daughter, thereby ensuring that one day Godwine’s grandson would rule England – or so Earl Godwine thought.

Before long, Earl Godwine saw his new plan destroyed. To everyone’s amazement, once married, King Edward took a vow of chastity. Edward said that it was a religious decision, but just as likely it was the best way to avoid producing a Godwine heir to the throne.

Earl Godwine was not deterred. He demanded the grant of earldoms to four other sons: Harold, Tostig, Gyrth and Leofwine. Then the Godwines started to exercise their power, refusing to obey Edward’s commands and inciting rebellion across the country.

When he was returning home after visiting Edward, Count Eustace of Boulogne stopped for the night in Dover. Eustace sent out some soldiers to seek lodgings, unaware that Earl Godwine had given instructions to the townsfolk not to be of any assistance. Encountering hostility, one of the soldiers killed a citizen; then a citizen stabbed the soldier, and a violent affray developed. Men and women were slaughtered, and children were trampled underfoot as the soldiers rode off leaving seven of their number dead.

Furious at the insult to his brother-in-law Eustace, King Edward ordered Earl Godwine to lay waste to the town. He refused, and the matter turned into a trial of strength between the Anglo-Saxon Godwines and Edward’s Norman favourites.

Within days, the two armies faced each other. However, Godwine hesitated and allowed negotiations to commence. The Norman Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert of Jumieges, announced that the Godwines were plotting to kill the King, and he appealed for assistance. Support soon arrived, and now that he was heavily outnumbered, Godwine was forced to accept Edward’s terms. Edward banished the Godwines from England, and he sent his own wife, Queen Edith (Earl Godwine’s daughter), to a nunnery.

Had it really been an attempt to kill Edward? All that can be said today is that if Godwine had attacked before Edward’s reinforcements arrived, Edward’s death would have been the likely result.

Across the Channel, the Godwines raised an army, and in 1052 they invaded England. King Edward was forced to reinstate all the Godwines to their former positions. But within a few months, Earl Godwine was dead; he had choked whilst dining with the King. Godwine lay speechless for three days, and then he died. A stroke is the accepted diagnosis, but murder was a reasonable suspicion. As if a motive were needed, Edward had invited Godwine to dinner in order to challenge him about the blinding and murder of King Edward’s brother, Alfred, all those years ago.

Regrettably for Edward, the elimination of Earl Godwine did not solve anything. Godwine’s second son, Harold, took his father’s place as Earl of Wessex and as the most powerful and troublesome man in the kingdom, the first son, Sweyne, having died whilst returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

There was another problem, and Edward had created it. With his declared chastity, he would never have children, so questions began to be asked about the succession. Who would be the next king? The main contender, still living in Hungary, was Edward the Exile, the son of King Edward’s half-brother, Edmund Ironside, Edmund’s other son having died. Edward recalled Edward the Exile, and in 1057 he landed in England with his wife and children. This solution failed when the Exile died two days after his arrival in London. Again, murder was a strong possibility, and Harold (who may have escorted the Exile on the last leg of his journey) was a prime suspect, perhaps the only suspect.

Having failed to deal with the succession, Edward was confronted with a more pressing matter. In 1065, there was a rebellion in Northumberland against the repressive rule of Harold’s brother, Tostig, who had doubled taxation. King Edward summoned his forces, intent on marching to Tostig’s aid, but the nobles, led by Harold, refused to obey the summons. The northern rebellion became ever more violent, and Tostig had to flee to Norway. Across the sea, the exiled Tostig would plot his revenge, having accused his brother, Harold, not just of failing to come to his aid, but of having incited the rebellion in the first place.

Edward, now elderly and frail, was the real loser. The nobles’ direct challenge to Edward’s authority shook him to the core. The distraught King fell ill, perhaps suffering a stroke. He lapsed into a coma, awakening at intervals, often delirious and talking nonsense. It would only get worse.

When Edward died in early 1066, he of course died childless. This left the Exile’s son, Edgar the Atheling (Anglo-Saxon for a noble or, as in this case, the heir to the throne), as the leading claimant by inheritance. He was only 12 years old; how could he rule the country? Someone else had to be found.

Edward’s nephews Ralph of Hereford and Walter of Mantes, the sons of Edward’s sister Godgifu, had once been possible heirs. However, Ralph had died in 1057, a broken man following a catastrophic defeat by the Welsh that left him known as ‘Ralph the Timid’, and Walter had died in 1064 while in the custody of Duke William of Normandy. The Duke’s eyes must already have been on the English crown.

In any case, heredity was not yet the sole basis for succeeding to a throne. It was usually obtained either by a deal, appointment by the former king, or by sheer power. As far as power was concerned, Harold had no rivals in England. In an effort to bolster his claim, Harold announced that on his deathbed, King Edward had nominated him as his successor, the ambiguous words said to have been: “I commend this woman [meaning Queen Edith, Harold’s sister] and all the kingdom to your protection”.

Other reports say that the dying king merely pointed at Harold. Its significance is a matter of conjecture. Whatever happened as Edward died, it is clear that the next day the Witenagemot (from Anglo-Saxon

gemot

– ‘meeting’, and

witena

– ‘of wise men’), a council of senior clerics and nobles, confirmed Harold as king. He wasted no time, and within 24 hours he had been crowned in Westminster Abbey.

Built on the site of a monastery, Westminster Abbey was Edward’s great legacy. It was named the west–minster to distinguish it from St Paul’s, which was the east–minster; a minster being a church or cathedral attached to a monastery.

Although Edward lived long enough to see the abbey completed, it was little more than that. Westminster Abbey had a busy first few days: on 28th December 1065 it was dedicated in Edward’s absence because of illness, on the morning of 6th January it hosted Edward’s funeral, and on the afternoon of 6th January it staged Harold’s coronation.

Edward was remembered as ‘Edward the Confessor’, that is a saint who had led a holy life. Worshipped by his successors, he became the patron saint of kings, difficult marriages and separated spouses. For a long time he was also the patron saint of England. During the fourteenth century he was replaced in that role by Saint George, yet Saint Edward the Confessor remains to this day the patron saint of the Royal Family.

In retrospect, Edward’s escape from murder at the hands of Harold Harefoot’s men before becoming king and by Earl Godwine’s men after becoming king enabled him to establish England as a country freed from the Danes.

But worryingly, the marriages of Emma of Normandy to Ethelred and then to Canute, both no doubt designed by the Normans to ensure a dynasty of Norman kings of England, had produced two kings of England (Harthacanute and Edward) who died childless. The Normans would have to try a less subtle method, and yet again it would involve the killing of a king.

HAROLD

5 January 1066 – 14 October 1066