Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (48 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

On the eve of Alexandrina’s eighteenth birthday, the two schemers made one last effort. The Duchess and Conroy demanded that Alexandrina sign a document under which she agreed that her minority would be extended to the age of twenty-one. Alexandrina had held out for so long, she was not about to stumble at the last hurdle. She did not sign.

With the death of William IV, Victoria became queen. Eighteen years old, just over 5ft tall and brought up in seclusion, she began her reign. Fortunately, for much of her reign there would be a man of experience on whom she could rely. The first such adviser was the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne (after whom the Australian city is named).

As soon as she became queen, Victoria asked to be left alone for an hour – something her mother and Conroy had never allowed. She moved into the recently completed Buckingham Palace where, to Victoria’s joy, she was allowed her own bedroom. The Duchess was sent to rooms at the far end of the Palace, convention demanding that being unmarried, Victoria must live in the same building as her mother. Conroy was excluded from court life, but he was still secretary to the Duchess.

Although Victoria was now Queen of the United Kingdom as the only child of the fourth son of George III, she did not inherit the crown of Hanover. The Salic Law applied in Hanover, a woman could not become sovereign. So Victoria’s uncle, Ernest Augustus Duke of Cumberland, became King of Hanover as the fifth son of George III. The 123-year link between the two countries was broken for ever.

If the Salic Law had applied in the United Kingdom, Ernest Augustus would have become king. Ernest Augustus was unpopular in England, a man rumoured to have murdered his valet, to have fathered a child by his sister Princess Sophia, and to have attempted to rape the wife of the Lord Chancellor. Victoria’s mother claimed that the reason she had made Victoria share a room with her was because she was frightened that Ernest Augustus would murder Victoria so as to gain the throne.

Ernest Augustus had fallen in love with his cousin, Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who was married to the Prince of Solms-Braunfels. The Prince conveniently died (poison was suspected), and Ernest married Frederica.

Once he was King of Hanover, Ernest revoked the liberal constitution and took absolute power. Ernest Augustus was succeeded by his son, George, who lost the sight of one eye through illness and then lost the sight of the other eye in a riding accident, so that he was blind at the age of thirteen. In the Austro-Prussian War, Prussia demanded that Hanover remain neutral. The Hanoverian Parliament agreed, but George was a supreme autocrat like his father; he overruled Parliament and supported Austria. As a result, Prussia invaded and annexed Hanover; it was the beginning of modern Germany. George lost his throne and went into exile.

He was succeeded in exile by his son, Ernest, who sided with Germany in the First World War. He was accordingly stripped of his title of Duke of Cumberland. In 1923 he was succeeded by his third son, Ernest (the first son having been killed when the car he was driving to the funeral of his uncle the King of Denmark went off the road and hit a tree, the second son having died of appendicitis). That third son married the daughter of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and was succeeded in 1953 by his son Ernest, who was succeeded by his son Ernest. Having divorced his first wife, that son is now married to Princess Caroline of Monaco.

So, if the Salic Law had applied in the United Kingdom, Ernest would now be king and Princess Caroline of Monaco would be queen, provided Ernest was not deprived of the crown under the Act of Settlement for marrying a Catholic.

Hypothetical as that may be, the reality was that for so long as Victoria had no children, Ernest Augustus was next in line in Britain. It was not a happy situation, with Ernest Augustus a reactionary autocrat and suspected murderer. Victoria hated Ernest Augustus, the ill-feeling inflamed when he demanded delivery of most of Victoria’s personal jewellery (passed down from Queen Adelaide), claiming that he was entitled to inherit the jewellery as the male heir of William IV. His son continued the claim and won the eventual arbitration; the jewels were handed over. India and South Africa would compensate Victoria’s loss.

There was only one way to deal with the problem of Ernest Augustus, and it would also take care of Victoria’s personal problem, her desire to evict her mother from the Palace – Victoria must marry and produce an heir.

It was clear to Victoria that her uncle Leopold wanted her to marry his nephew Albert (the younger son of Leopold’s and the Duchess’ older brother), who was Victoria’s cousin. Albert was sent to England in October 1839 to take matters further. When he was four years old, Albert’s parents separated and were later divorced. Albert’s mother was banished from court, and she married her lover; Albert was never allowed to see his mother again. Then Albert’s father married his niece, Albert’s cousin.

This time Albert’s visit was successful; Victoria was attracted by his good looks, and before long her mind was made up. Of course, as queen it was for her to propose – or at least to tell Albert of her decision. She did so; they were deeply in love, both aged twenty. They married in St James’s Palace in February 1840, Victoria introducing the custom of the bride wearing white. So, one of Albert’s cousins was now his stepmother and another cousin was now his wife.

However, not everyone was enamoured with the young queen. In the late afternoon on most fine days, Victoria and Albert took an open carriage ride through the royal parks. An 18-year-old man from Birmingham, working at the Hog-inthe-Pound pub in Oxford Street, knew of this practice, as did many people in London.

Henry Oxford made his way to the Blackfriars Road, where he bought a pair of pistols for £2. Over the following days, Oxford went to shooting galleries in Leicester Square and the Strand, where he practised shooting at a moving target.

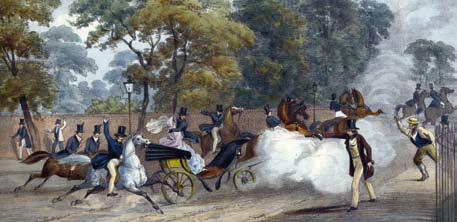

On the afternoon of Wednesday 10th June 1840, Oxford went to Constitution Hill (so named because Charles II used to take a ‘constitutional’ walk there), which runs along the side of Buckingham Palace, and he waited for the royal coach. At six o’clock, the low open carriage drawn by four horses with two outriders ahead, and carrying Victoria and Albert, set out from Buckingham Palace, turned left and proceeded along Constitution Hill. Oxford was standing on the far side of the road, by the railings dividing Constitution Hill from Green Park. When the carriage came close, he aimed his pistol and shot at the Queen. He missed. Oxford then drew the second pistol and fired. He missed again. The carriage raced away.

Out of the many watching, a man named Lowe rushed forward, grabbed Oxford and took the two firearms. Others hurried to the scene, and seeing Lowe with the pistols, they believed him to be the assassin.

“You confounded rascal! How dare you shoot at our Queen?” But Oxford stepped forward. “It was I,” he said.

A search of Oxford’s lodgings revealed more bullets and powder, and some documents relating to a revolutionary society called ‘Young England’, presumed to be Oxford’s invention, as no other members were ever discovered.

At his trial for treason at the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey), Oxford pleaded ‘not guilty’. Oxford’s counsel contended that as no bullets had been found, the pistols were not proven to have been loaded. Second, he said that as she had not been hit, that was evidence that Oxford was not trying to kill the Queen; he intended to miss and was only trying to frighten her. The third defence was insanity. Counsel proposed that Oxford must be insane because no sane Englishman would try to kill the sovereign, and the proof was that all previous assassination attempts on British sovereigns had been by madmen.

More credibly, witnesses, including Oxford’s mother, gave evidence of his bizarre behaviour and the mad conduct and brutality of his father. Medical evidence supported them. After a two-day trial, the jury found Oxford not guilty by reason of insanity. He was sent to Bedlam to be detained during Her Majesty’s pleasure. Several years later, the doctors declared that they could find nothing wrong with Oxford, and he was released on condition that he left the country. He went to Australia, where he was imprisoned for theft and then for vagrancy. A later report suggested that he had changed his name to John Freeman and published a book; another that he became a house painter.

Oxford’s assassination attempt

Oxford’s assassination attemptNow the young queen dealt with enemies at home. She moved her mother out of the Palace. Conroy accepted that his ambitions would never be fulfilled, and left for the Continent (questions were being asked about major discrepancies in the Duchess’ accounts and in the accounts of Princess Sophia, Victoria’s great-aunt). Victoria’s joy was completed when Princess Victoria was born. It was the first time an English or British queen regnant (as opposed to the consort of a king or Anne before she acceded) had given birth.

An election brought the Tories to power in 1841. Lord Melbourne was replaced by Robert Peel, a man Victoria did not like. With that change, she began to rely on Albert, who as a foreigner had not been allowed to interfere in political matters, not even to discuss them with his wife. In fact, Albert was denied a peerage so as to keep him out of Parliament and prevent him from meddling in politics and matters of state.

On 28th May 1842, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were travelling through St James’s Park in an open carriage. Waiting for her with a pistol was 19-year-old John Francis, a man who was outraged at the cost of maintaining the Royal Family. As the Queen passed close to him, Francis took out the pistol, aimed at the Queen and pulled the trigger – but the gun did not fire. No one had noticed, and Francis ran away. He returned the next day, as the Queen and Albert took the same route. This time Francis aimed, fired and missed. He was immediately seized, and was later tried for treason. Francis was convicted and sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted, and he was transported to Australia for life.

Then, on 3rd July 1842, the day after Francis’s sentence was commuted, another young man, 18-year-old John William Bean, decided to imitate Francis. He was lying in wait for Victoria as she passed by in her carriage. Bean aimed at Victoria and fired his old flintlock pistol. However, it was loaded with paper and tobacco, so it was hardly a genuine assassination attempt. Nevertheless, it was treason. A declared anti-monarchist, Bean said that he was tired of life and wanted to die.

Albert believed that Francis and Bean had been encouraged by Oxford’s acquittal. He also believed that death was far too severe a penalty for Bean. Discussions with ministers led to the speedy passing of the Treason Act of 1842. Under this Act, assault with a weapon in the monarch’s presence with the intent of injuring or alarming the monarch was made punishable by up to seven years’ transportation or up to three years’ imprisonment, and during the imprisonment to be publicly or privately whipped not more than three times. Tried for this lesser offence, Bean was convicted and sent to prison for 18 months. No one ever received a whipping.

In time, Victoria managed to establish a working relationship with Peel, but a problem arose when he was replaced by Lord John Russell who appointed Lord Palmerston to the office of Foreign Secretary. It was a period of revolutions and uprisings threatening just about every throne in continental Europe except Russia. Palmerston opposed autocratic rulers, and he supported those who demanded constitutions in foreign countries, as well as those who sought independence. Victoria, on the other hand, was related to those autocratic rulers, and wanted Britain to assist them. She was totally against any insubordination by subjects.

However, Palmerston was backed by the British people, who admired his strong attitude towards other countries and his policy of increasing British power throughout the world. The main issue was that Victoria and Albert favoured Germany in various territorial disputes, Palmerston always took the side of their opponents.

Surprisingly, it was Greece that next felt the force of Palmerston’s principles. Surprising, because he was a lover of Greece and had been instrumental in using Britain’s power to obtain Greece’s independence. But in 1847, David ‘Don’ Pacifico, the Portuguese consul in Athens, was a victim of anti-Semitic riots encouraged by the Greek Government, and soldiers looked on approvingly as Jews were attacked and their homes were ransacked and set ablaze. Don Pacifico’s house was destroyed. But Don Pacifico had been born in Gibraltar, and he was therefore a British citizen. So Palmerston sent the fleet to blockade Athens’ harbour, Piraeus, until the Greeks paid Don Pacifico compensation. After two weeks of blockade, the Greeks paid up. Of course, the House of Lords condemned Palmerston’s support of a Jew; but the House of Commons was with him, inspired by his five-hour oration, known as ‘the Civis Romanus sum speech’. In it Palmerston said, “As the Roman in days of old held himself free from indignity, when he could say ‘I am a citizen of Rome’, ‘

Civis Romanus sum’

, so also a British subject in whatever land he may be shall feel confident that the watchful eye and the strong arm of England will protect him from injustice and wrong.”