Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (49 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

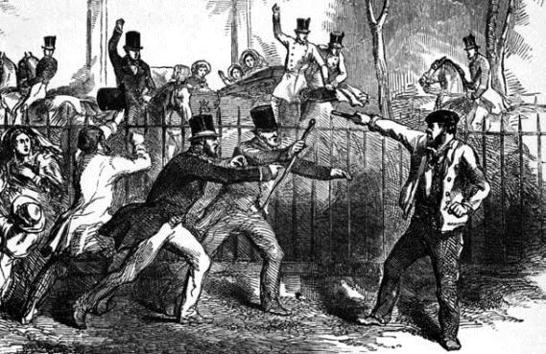

Memories of past attacks were revived in May 1849. On a sunny day in the late afternoon, Victoria, accompanied by three of her children, left Buckingham Palace in an open carriage on a drive through several parks. Prince Albert was riding alongside. When they left Regent’s Park, Prince Albert rode on to return to the Palace. The others continued, and after crossing Hyde Park, the carriage turned into Constitution Hill. An angry unemployed 17-year-old named William Hamilton, recently arrived from Ireland, was waiting for them. Earlier that afternoon, Hamilton, who lived nearby in Ecclestone Place, had gone to his landlord and had asked to borrow a pistol, saying that he wanted to shoot some birds. With the old-fashioned pistol in his pocket, he walked to Constitution Hill and waited behind the railings on the border with Green Park.

Seeing the carriage approaching, Hamilton moved forward, took out the pistol and fired at the Queen. He missed. Inspection of the pistol suggested that it may not have been loaded. Hamilton was charged under the 1842 Treason Act. He pleaded guilty, and was sentenced to seven years’ transportation to a penal colony in Australia.

Hamilton’s assassination attempt

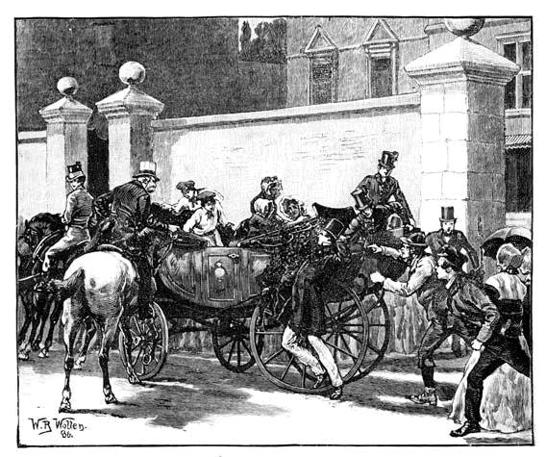

Hamilton’s assassination attemptAdolphus Duke of Cambridge, Victoria’s uncle, was nearing death. On the afternoon of 27th June 1850, Victoria went to her uncle’s residence at Cambridge House in Piccadilly to pay her last respects. Shortly after six o’clock, she left to go home. Victoria climbed into her carriage, and the journey began. As the carriage was leaving the courtyard, a man ran forward. He was Robert Pate, a former Lieutenant in the 10th Light Dragoons. Pate was carrying a brass-topped cane. On reaching the carriage, Pate leaned in, raised his cane and struck the Queen repeatedly about the head until he was dragged away. Fortunately, like her uncle William IV at Ascot, Victoria was wearing a hat. The bonnet took some of the force of the blows. Nevertheless, Victoria was heavily bruised by the attack, also suffering a black eye.

No motive for the assault was ever discovered. Pate was charged under the 1842 Treason Act. The plea of insanity was supported by medical evidence, but the judges found him sane. Pate was convicted and sentenced to seven years’ penal transportation to Van Diemen’s Land. After serving his sentence, Pate stayed on in Australia, and is said to have made a considerable sum of money mining gold. Years later, on hearing of the death of his father, Pate returned to England. His father had been Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire; he had also been a successful corn trader, and he left a substantial estate. With his share of the inheritance, Pate settled in his home town of Wisbech, to live with his wife.

Pate’s attack

Pate’s attackConstitution Hill finally gained a victim in 1850. Former Prime Minister Robert Peel was riding past the gate to Green Park after calling at the Palace, and was thrown by his horse and then killed when the horse fell on him. Peel is credited with introducing the Police Force, policemen being popularly called ‘Peelers’ after his second name, and then ‘Bobbies’ after his first name. He had opposed Catholic emancipation, and had therefore been given the nickname ‘Orange Peel’, the Irish Protestants being called Orangemen after their hero, William of Orange.

Victoria’s reign saw a massive increase in population and a shift to industrialisation. The positive side of progress and Britain’s self-confidence was portrayed in the Great Exhibition of 1851. This was Albert’s triumph; 13,000 exhibitors contained within the Crystal Palace built in London’s Hyde Park, extending across 26 acres. It included the world’s first public toilet, and more than 800,000 visitors ‘spent a penny’ – the price for its use. Parliament had refused to finance or even guarantee payment of the cost of the Exhibition, so it was left to Albert to find individuals willing to provide the necessary money. The £186,000 profit was used to buy land and build museums in South Kensington in London along and around what is now Exhibition Road, an area with buildings and memorials dedicated to Albert and therefore informally known as ‘Albertopolis’.

Overseas, serious trouble was coming. By 1851, the Ottoman Turkish Empire (founded by Osman I, who was called ‘Ottoman’ by the Europeans) was disintegrating. Russia, always eager to increase its territory, was eyeing the Black Sea. France gave them the excuse. The Holy Land had been a Turkish territory since 1517, and the French pressured the Ottomans into confirming France and the Catholic Church as the supreme Christian authority there, so taking control of the Church of the Nativity from the Greek Orthodox Church. Naturally the Russians were outraged, and the Tsar ordered his armies into Moldavia and Wallachia, which were both under Ottoman rule.

Britain was determined to halt Russia’s territorial enlargement, fearing that their next step would be to expand into the Mediterranean. The British and French fleets were sent to the Dardanelles – a long narrow straight connecting the Aegean Sea with the Sea of Marmara, and therefore dividing Europe and Asia Minor. In October 1853, the Sultan declared war on Russia. The Russians promptly destroyed a major part of the Ottoman Navy. In response, Britain and France declared war on Russia; it was the start of the Crimean War.

Before long, Russia withdrew from Moldavia and Walachia (later united as Romania); but the war had already acquired a momentum, and the British and French wanted to end the Russian threat to the Ottomans. The focus of the war was Sebastopol (on the Crimean peninsula, located to the north of the Black Sea), the home port of the Russian Black Sea fleet. British and French armies besieged the city, which fell after a year. Fighting continued as the allies tried to move forward, but with little success. From beginning to end, the war was marked by incredible incompetence in the leadership of both sides, and casualties were high.

Then Tsar Nicholas I died, and in 1856 his successor Alexander II agreed terms of peace. Russia was forbidden from establishing military or naval bases on the Black Sea coast, and the pre-war treaty under which only Turkish warships could traverse the Dardanelles in peacetime was confirmed. It was merely a delay; the Russians attacked the Ottomans again 20 years later, leading to the independence of Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia and Montenegro.

By 1857, Victoria had given birth to nine children over a period of seventeen years: Victoria, Edward Prince of Wales, Alice, Alfred, Helena, Louise, Arthur, Leopold and Beatrice. Unusually, all survived infancy and all would be married. Alice and Leopold died in their thirties, the others all lived beyond 55, some by a long way. Albert was appointed prince consort; acceptance of the foreigner was now almost complete.

There were problems with two of the children. Leopold, the eighth child, was a poorly baby. He was found to be suffering from haemophilia, a genetic disorder that impairs blood clotting or coagulation. No scab forms, and even in the case of a minor injury or bruising the bleeding goes on for a long time, in some cases until death. Haemophilia is incurable, although nowadays it can be controlled with regular infusions of the deficient clotting factor.

It is mainly suffered by males. Females have two X-chromosomes, so if one is defective the second one compensates. Males have only one X-chromosome, so if it is defective they will suffer haemophilia. As a result, if they have the defect, men are always carriers and sufferers. A woman with the defect is generally only a carrier; but if she inherits the defect from both parents, so damaging both X-chromosomes, she will be a carrier and a sufferer – but this is very rare.

A carrier and sufferer will always pass it to a daughter; if a man, he never passes it to a son, if a woman, she has a 50% chance of passing it to a son. A woman who is merely a carrier has a 50% chance of passing it to all children.

Clearly the defect must have come from Victoria, as a man could not be a carrier without being a sufferer, which Albert was not; anyway, a man does not pass it to a son. It was a surprise, as there was no history of the disease in the Royal Family. Nor was there evidence of the disease in the family of Victoria’s mother or in Victoria’s half-sister and half-brother and their descendants. Studies show that about 30% of haemophilia cases are not inherited; they are spontaneous gene mutations, suddenly starting in one person – and with three of Victoria’s daughters passing the disease to descendants, it must have originated in Victoria, not Leopold. Now both haemophilia and porphyria were diseases of the Royal Family.

The other problem concerned the second child, Edward Prince of Wales, heir to the crown. His parents wanted him to be studious and responsible like his father, but he turned out to be unacademic and pleasure-loving like his Hanoverian great-uncles. He was a grave disappointment to his parents.

It was time for celebration when Victoria’s first child, Princess Victoria, married the son of the King of Prussia. In 1859, she gave birth to Queen Victoria’s first grandchild, William – eventually to become the Kaiser. Two years later, Victoria’s great happiness came to a sudden halt. In March 1861, Victoria’s mother died. The Queen had become reconciled with her mother, largely through the efforts of Albert (the Duchess was after all not just his mother-in-law, but also his aunt), and Victoria was very upset when she died. Far worse was to come.

There were more of the usual problems with the behaviour of the Prince of Wales, particularly his involvement with an actress. Albert, though feeling unwell, travelled to Cambridge to lecture his son. When Albert returned to London, he immediately suffered severe rheumatic pains. On 14th December, just two weeks after returning from Cambridge, Albert died of typhoid at the age of forty-two.

Victoria was absolutely shattered; she mourned for the rest of her life. She resolved that the remainder of her reign would be spent in putting Albert’s wishes into effect. For a start, their third child, Princess Alice, married Prince Louis of Hesse. Then Victoria arranged for the Prince of Wales to marry Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Of course, Victoria would not attend any of the festivities.

The fourth child, Alfred, was offered the crown of Greece after the dethronement of the German-born King Otto. Victoria turned down the offer as Albert had decided that Alfred should succeed to the title of Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on the death of Albert’s childless older brother (Prince Edward having waived his prior right to the dukedom).

In 1868, Prince Alfred was sent on a world tour; it included the first royal visit to Australia. Alfred joined the Sailors’ Picnic on a beach near Sydney. Henry O’Farrell, sidled up to the Prince and shot him in the back. Police seized O’Farrell in time to prevent the angry crowd from lynching him; it would only be a delay. It was claimed that O’Farrell was acting for an Irish nationalist organisation. He was certainly violently antiBritish and anti-monarchist, but it seems that he was acting alone. Although he had a history of mental illness and had only recently been released from an asylum, the plea of insanity was rejected. He was sentenced to death and was hanged, despite Alfred’s plea for clemency. Of course, the alternative sentence of transportation was not available – he was already in Australia. Having spent two weeks in hospital, Alfred was able to return home.

After years of mourning by Victoria, the British public felt that it had gone on for long enough. Convention set the mourning period for a husband at two years; for a wife, it was six months. However, Victoria just could not put her grief aside. For 40 years she would insist that at Windsor Castle, Albert’s clothes were laid out and that hot water was brought to his room every morning, and that his linen and towels were changed daily.

Two very different men came to Victoria’s rescue. Having managed working relationships with Prime Ministers Lords Derby, Aberdeen and Palmerston, a new era opened as Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the Conservative Party (the protectionist Tories who remained after the Peelites joined the Whigs to form the free-trade Liberal Party), slowly drew Victoria back into public life. She opened the new Albert Hall in 1871, although when it was time for Victoria to mention the name ‘Albert’, she was overcome with emotion and the Prince of Wales had to speak the necessary words. Nevertheless, Victoria was still unpopular with the masses. Their view was that she was not doing the job she was paid to do, and she should abdicate.