Atlantic (37 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

Maritime laws and regulations in legions—among them laws that extended well beyond those relating to ending the shabby treatment of migrants—were changed in consequence of the

Titanic

’s collision with her fateful iceberg. The irony of the coincidence of location can hardly have escaped notice: new laws regulating passage by sea were occasioned by a terrible tragedy that took place in the North Atlantic in 1912; the very system of laws and the organization of parliaments to decide and promulgate them was first created but a few hundred miles away, in Iceland, in 903—almost precisely one thousand years before.

7. CASUALTIES AT SEA

Invariably it took accidents at sea to effect changes to the laws of the sea. And many of the most important recent maritime accidents took place, as with the

Titanic

, along some of the Atlantic’s busiest shipping lanes. Our ability to discern this in an instant is due to a forgotten nineteenth-century polymath named William Marsden,

71

who while employed as secretary of the Admiralty was professionally interested in collecting and collating statistics about the world’s seas. He divided a Mercator map of the world into a series of numbered ten-degree squares, known to this day as Marsden squares.

Each quarter of every year, the insurers at Lloyd’s produce a casualty report—a list of vessels involved in accidents at sea and that, either through foundering, colliding, or being wrecked, were reported to have been either total losses or so seriously damaged as to require towing and rebuilding. These figures are all then plotted as black dots on a Marsden squares chart of the world, the results showing up as concentrations of accidents in all the places one might expect—in the crowded waters off Singapore, in the Black Sea, south of Sicily, in the southern Aegean.

But the Atlantic has a pall of problems on both of its coasts. Enormous numbers of accidents are reported each year along the shores of Norway and western Scotland, within the entire length of the English Channel, in south Wales, by Rotterdam, in Galicia, along the Spanish side of the Strait of Gibraltar, by Lagos and the approaches to Cape Town. South America, on the other hand, gets off comparatively lightly—squares 413 and 376, which include the entrances to the ports of Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, show some activity—but then once the Caribbean and the North American coasts come into view, the maps swiftly turn black with pepperings of ink around the southern coast of Haiti, along the Gulf of Mexico coast from Mobile to Galveston, the length of Long Island from the Nantucket Light to New York City, and along the entirety of the St. Lawrence Seaway. Marsden square No.149, where the

Titanic

foundered, has just a scattering of dots, since accidents out in the deep sea occur only infrequently—though when they do, rescue is invariably slow to arrive and most often is too late.

Coastlines, and other ships, are what sailors fear most. Most of the infamous recent accidents have taken place within sight of land. The collision of the two passenger liners

Andrea Doria

and the

Stockholm

less than twenty miles west of Nantucket in 1956, in thick fog, became a legendary story of rescue (of the 1,706 passengers, 46 were killed) and an object lesson—resulting in yet more modified rules—in when not to rely on radar. Arguments over apportioning the blame for the costly collision between the Liberian oil tanker

Statue of Liberty

and the Portuguese cargo carrier

Andulo

off the southwestern tip of the Iberian peninsula in 1965 were so intense they had eventually to be decided by the British House of Lords, since Lloyd’s insurance claims are adjudicated there (the Liberian ship lost, being found “85 percent to blame”). And the stranding and sinking of the fully laden Liberian oil tanker

Argo Merchant

, which hit a reef off Nantucket at sixteen knots while making passage from Venezuela to Boston in 1976, resulted in 28,000 tons of oil being blown out to sea, and the then American president announcing new rules regarding pollution, navigation, and preserving life on the ocean.

The crippled Italian liner

Andrea Doria

lies on her starboard side after being struck by the Swedish liner

Stockholm

in the open sea approaches to New York on the foggy night of July 25, 1956. Arguments still flare over how to apportion blame for this “radar-assisted collision,” in which forty-six crew members and passengers died, though nearly 1,700 were saved.

Probably the most memorable of recent oil tanker disasters was that involving yet another Liberian vessel, the

Torrey Canyon

, which in March 1967 was steaming at full tilt toward southwest England, with 119,000 tons of Kuwaiti crude oil for the refineries at Milford Haven, in south Wales. The repercussions of her hitting, head-on, the sharp granite rocks of the Seven Stones Reef, off the Scilly Islands, were even more widespread—in terms of new laws and international agreements—than after the

Titanic

. The laconic, matter-of-fact tone of the official report, as summarized in the

Times Atlas of the Oceans

, takes nothing from the gravity of the disaster:

At 08.40 the position was fixed by observation of the Seven Stones light vessel—it was bearing 033ºT at a range 4.8nm [nautical miles]. The

Torrey Canyon

was now only 2.8nm from the rocks ahead.

At 08.42 the master switched from automatic steering to manual, and personally altered the course to port to steer 000ºT, and then switched back to automatic steering.

At 08.45 the third officer, now under stress, observed a bearing, forgot it, and observed it again. The position now indicated that the

Torrey Canyon

was less than 1nm from the rocks ahead. The master order hard-to-port. The helmsman who had been standing by on the bridge ran to turn it. Nothing happened. He shouted to the master who quickly checked the fuse—it was all right. The master then tried to telephone the engineers to have them check the steering gear aft. A steward answered—wrong number. He tried dialing again—and then noticed that the steering selector was on automatic control instead of manual. He switched it quickly to manual, and the vessel began to turn. Moments later, at 08.50, having only turned about 10º, and while still doing her full speed of 15.75 knots, the vessel grounded on Pollard Rock.

A number of cargo tanks were ruptured, and crude oil began immediately to spread around the vessel. . . .

With 120,00 tons of Kuwait crude oil in her tanks, a shortcut in the sailing plan, and the ship’s cook at the wheel, the California-owned, Liberian-registered supertanker

Torrey Canyon

was going full tilt when she struck the Seven Stones Reef off Cornwall in March 1967, causing an environmental catastrophe.

The British government eventually had to bomb the wreck with napalm—causing an additional flurry of comment, since up to this point few in the country were aware that Britain possessed the gelled-gasoline weapon then being used to such dreadful effect in Vietnam—to set fire to the spreading blaze. The court battles over the costs of the affair, and the international conferences called to consider its environmental consequences and legal and political ramifications, continued until the middle of the next decade.

Most tragedies at sea, melancholy though they may be for those involved, are events in the faraway that are invariably soon forgotten. Some—like the rescue of the men and women from the

Forfarshire

by the wonderfully named Grace Darling, in her rowboat in a storm off the Farne Islands in the North Sea in 1838—are remembered for offering up an episode of exceptional heroism. Others—like the two-masted brig

Mary Celeste

, found six hundred miles west of Portugal, sailing steadily toward Gibraltar with not a soul aboard—remain in the mind because of the mystery, in this case a puzzle amenable to so many possible causes (murder, poison, sea monster, tsunami?), very few of them good. And then there was the fate of the

Teignmouth Electron

, the tiny catamaran in which the British amateur sailor Donald Crowhurst had entered a round-the-world single-handed yacht race. He had cheated, had then found himself likely to win and thus most probably to be placed under scrutiny, and so had leapt off his craft to avoid discovery: the story lingers still, a vivid portrait of man made manically mad in the wide loneliness of a great ocean.

• • •

The vastness and imperturbable power of the sea, when ranged against the enforced solitude of a lonely sailor, can surely make for madness. It can also prompt in others a soaring of ambitions, a realization of great visions, perhaps for some the making of great fortunes. But in all these encounters with a sea so grand as the Atlantic, there has to be the presumption that the body of water itself inspires a large measure of respect and awe. If that inspiration wavers—if mankind ever begins to treat the sea with less respect than its own story deserves—then things begin to go awry. A great ocean is not a thing to regard with casual disdain: but in the manner and speed with which it is being so often traversed today, there is the rising of temptation to do just that. The consequences are myriad, and they are invariably malign.

The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound.

1. CROSSING THE POND

At the international operations center of British Airways, which takes up the entire third floor of a highly secure and discreetly marked building on an empty moor some five miles west of London’s Heathrow Airport, the staff takes care to refer to every transoceanic flight as a “mission.” They do so in part out of tradition; but they do so also as a reminder that, just as with today’s explorations of space and with nineteenth-century ventures into godless interiors, there is never anything inherently routine or safe about their allotted task: in this case the lifting against the natural force of gravity of two-hundred-odd tons of airplane and three-hundred-odd human beings to an entirely unsustainable altitude of seven or so miles, and then propelling all without interruption for many long hours, suspended by nothing more than a lately realized principle of physics, high above a cold and highly dangerous expanse of sea.

Air travel across oceans has in recent years become to most consumers, if not necessarily to the practitioners, as tedious as it is commonplace. Its relative cheapness has rendered brief visits to the faraway perfectly imaginable to enormous swaths of society. The Atlantic, being of a width manageable for most to cross by air today without too much time or pain, is currently the most obvious pathway for millions to the most exotic of foreign fields. The Pacific is just too big; the Indian Ocean for most just too far away. So Mancunians who back in the 1970s might have considered Marbella an alluring mystery now in the first decades of the twenty-first century readily consider Miami an obvious destination for a long weekend. Parisians cross the Atlantic almost without thinking for tanning vacations in Martinique. Bored Brazilian city dwellers fly to see the giraffes and springbok near Cape Town, Belgians go in herds to sun in Cancún, Texans set off to visit the theaters in London, and Norwegians head southwest to try the slopes in Bariloche. All of this flying—together with the cargo and the courier planes trundling windowless through the nights, and with official government aircraft on routine business and military planes on secret missions—has conspired to make the Atlantic, of all the oceans, more flown across than any other.

The air-route charts present a quite alarming illustration, seeming as they do to render the ocean almost solid with passing traffic. They show in particular two great paint daubs of tracks between the American Northeast and the European northwest, so concentrated when they join just south of Iceland as to make the ocean appear almost paved, a yellow brick road in the sky. South of this thick northern superhighway are cobwebby skeins of routes linking former possessions with former masters—Mexico with Madrid, Curaçao with Amsterdam, Guadeloupe with Paris, Kingston with London, even (if to stretch a point) Havana with Moscow; while farther south still there is a thick line of the major north-south air tracks, nearly as concentrated as their east-west brethren, linking the great and growing cities of Atlantic South America with their main trading partners, old and new—Rio with Lisbon, of course, but also with Frankfurt and Moscow and Milan; and Buenos Aires with Barcelona, of course, but also with Stockholm; Birmingham, England; and Istanbul. And then even more distant, over the cold waters of the far South Atlantic, there are the lonely and half-forgotten tracks of the lesser-known city pairs: Rio de Janeiro to Lagos, Quito to Johannesburg, Santiago to Cape Town, Brasilia to Luanda.

More than thirteen hundred commercial aircraft cross into Atlantic Ocean airspace every day, and the number increases steadily, by about 5 percent each year. By far the greatest number of the planes fly across the northern part of the hourglass-shaped sea—414,000 planes checked in with its major oceanic air traffic control centers in the north during the calendar year 2006, for example. If to these are added the planes that cross from the South Atlantic up into the North and come back again, and the relatively few aircraft that cross just between the South American and African destinations, and in doing so fly over the lonely Atlantic waters to the south of the Tropic of Capricorn, then one comes up with a total figure of around 475,000 Atlantic transits every year: some 1,301 flights each day.

They do their crossing in two great waves, which in a time-lapse animation of the radar contacts look like spurts of molten gold radiating from the continents and out over the sea. First come the westbound jets trying in vain to chase the sun

72

by traveling generally in daylight; in contrast those going east, heading back into the Old World, fly out in the American darkness and land, by and large, early in the European morning. At any one hour of day or night there are perhaps fifty of these aircraft in flight over the sea—ten thousand human beings passing by every hour, reading, sleeping, eating, watching movies, writing, seven miles up in the sky.

• • •

And yet from these little seven-mile-high cities in flight, only a very few of the populations will ever care to look down for more than an inquisitive instant at the wrinkled surface of the sea below, or at the thick mass of gray-white cloud that so frequently obscures it from view. These people are mostly quite careless of the ocean’s very existence: it is merely an expanse to be crossed—

the pond

, if it is crossed quickly and casually, or something irritating and even less flatteringly named if it takes their aircraft countless hours to traverse.

The fact of inexpensive transoceanic travel has taken much the mystery of the sea away, has made us indifferent to its existence. Since the crossing of oceans has become tedious to most who do it, the oceans themselves have become the object of tedium as well. Once they were feared; they inspired awe, amazement, and mystery. Now they are to many just a barrier, an inconvenience—too large as entities properly to contemplate, too annoying as presences to warrant much care. The public attitude to the great seas has changed—and this change has had consequences for the great seas, few of them any good.

It has helped in particular to set the scene for what some worried few see as the endgame of humankind’s Atlantic story. It is nothing very new, of course. Man has been carelessly despoiling the oceans for decades. Ever since the first factory was built beside the water, ever since the first sewer pipe was laid in an industrial port city, and ever since we started, either casually or deliberately, to spill our wastes and our chemicals into the ocean’s immense and blameless sink, we have displayed a propensity to ruin it, to violate it. The land we have to live with, and so we pay it some measure of attention; the ocean, by contrast, is largely beyond our sight. It is so immense it can tolerate—or so we used to think—an immense amount of systemic misuse.

In Victorian times, though, we still thought of the ocean as vast and frightening; we still regarded it with some kind of awed respect. Not anymore. Passenger aircraft have shrunk the Atlantic’s vastness to a manageable size and thereby have also shrunk our capacity to be so impressed by it. People sail across the Atlantic on their own these days, and in summertime almost as a matter of routine. The westbound sailing route from Cornwall to the Caribbean by way of the Azores is regarded as so easy of accomplishment as to be referred to disparagingly by the harder-nosed and misogynist yachtsmen as merely “the ladies’ route.” Some people have taken to rowing across the Atlantic, at first in pairs, then alone. One day someone with a lot of spare time and a willingness to be swaddled in many tons of grease will probably contrive to swim it. The ocean is no longer so challenging a prospect as it once was. It stands in the public imagination rather as Mount Everest once did: now that we have

conquered

it, we perceive it as somehow manageable, and on the way to being even, dare one say it, trivial.

And in lockstep with this change of perception—not necessarily caused by it, but certainly coincident with it—there has been a steady lessening, some would say an actual abandonment, of humankind’s duty of care toward it. Such has already happened to Mount Everest: the base camp near Thyangboche is a slum, and the main route by way of the Western Cwm is strewn with castoffs; even the summit has as much junk on it as it does joyous flags. And now we are doing much the same to the world’s seas, dealing all too thoughtlessly with them in ways that many say are threatening the seas’ serenity, if not their very survival.

The oceans are under inadvertent attack, and as never before. Insofar as the Atlantic Ocean is the most used, traversed, and plundered of all oceans, so it is the body of water that is currently most threatened. Even though the central Pacific has attracted a lot of recent infamy because local gyres have swept a spectacular amount of ugly flotsam into mid-ocean patches the size of small states, it is actually the Atlantic that is in the greater trouble. It is subject to much more use—and so very much more misuse—all of it crammed into a much smaller space. It was the first great body of water to be crossed, it is now by far the busiest and is inarguably the most vital—but it has become evidently the least pristine and the most begrimed.

Yet awesome it remains, to some. In the British Airways operations center—a place of numberless computer screens and charts and weather forecasting maps and enormous panels of flashing pixels, and with dozens of serious-looking men and women

73

who are charged with keeping tabs on all the people, animals, and boxes of freight currently in flight around the world, and making as sure as they could that all of them were safe and on schedule and the people as content as it is possible to be on an airplane—there is little doubt that to all of them, twenty-four hours a day, the great ocean is still held very much in awe. Great seas are not kindly entities over which to fly: if your aircraft somehow fails, where, exactly, do you put down? No pilot leaves the chocks for a transoceanic flight without remembering the first axiom in flight school:

takeoff is voluntary, but landing is compulsory

. And in the middle of an ocean it is self-evidently true not just that there is nowhere to land, but that there

just is no land. No land at all.

Those who pioneered the practice of flying over seawater knew that all too well. Crossing a large expanse of sea perhaps didn’t trouble Louis Blériot when he flew his tiny monoplane across the English Channel from Calais to Dover in 1909, just six years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. For although Blériot admitted to being alone above “an immense body of water” for fully ten minutes, he also had the comfort of knowing a French destroyer was below him, monitoring his flight and ready to save him if he ditched. And for most of his thirty-seven-minute crossing, and even though he was only 250 feet up in the air, he could see the coast of France behind him and by peering ahead the white cliffs of England before him. Blériot won the thousand pounds that Lord Northcliffe had offered through his newspaper, the

Daily Mail

, and he became—not least because his boulevardier’s mustache and his reputation as a barnstorming air racer—an immediate superstar, and very much the ladies’ heartthrob.

But it was one thing to cross the Channel, quite another to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Lord Northcliffe put up ten times the sum for anyone who dared try it; and though he announced it in 1913, it was not until six years later (with admittedly, a four-year hiatus for the Great War to pass) that the prize was won, and by a pair of Royal Air Force officers whose names, by a small injustice of history are still not quite as known as that of Blériot: Jack Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown.

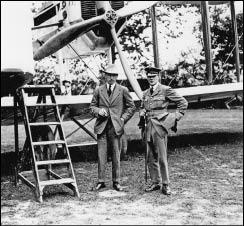

Jack Alcock (left) and Arthur Whitten Brown

, standing beside a Vickers Vimy heavy bomber in which they and their two pet kittens crossed the Atlantic nonstop in June 1919.

The venture was Alcock’s idea, conceived when he was imprisoned by the Turks after ditching his fighter plane in the sea near Gallipoli.

Why not have a bash?

he said. The pair used for the attempt a stripped-down long-range Vickers Vimy biplane, its bomb bays filled with extra fuel. In the summer of 1919, they dismantled the plane and crated it up so it could be sent by ship to Newfoundland. There they built their own runway for takeoff. They did not know where they might land—it could be a field, or a beach, or an Irish lane: it turned out to be a bog.

Plenty of others were trying for the same prize—among them an American, Albert Cushing Read, who flew a seaplane to the Azores, stayed there for a week, and then flew on to Portugal: it took eleven days, and American warships were stationed under his path every fifty miles along the proposed route. However, Lord Northcliffe had decreed that his prize was for a nonstop journey, achieved in less than seventy-two hours, so Read did not win it. Nor did a Australian tearaway named Harry Hawker, who tried it in an experimental long-range plane, a Sopwith Atlantic. When its engine overheated, Hawker spotted an eastbound ship five hundred miles short of Ireland and ditched; he was picked up and went home by sea. Because the ship had not yet acquired a radio, its crew could not tell Hawker’s relatives of his rescue. Instead Mr. and Mrs. Hawker were shocked to get an official black-bordered telegram from King George offering royal condolence for their son’s supposed loss. The better news came later.