Atlas (16 page)

Authors: Teddy Atlas

Me and Michael Moorer at the weigh-in, two days before the 1994 Holyfield world title fight at Caesars Palace, in Las Vegas.

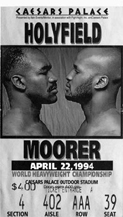

A ticket for the Holyfield-Moorer fight in 1994. Ringside seats went for $1,000.

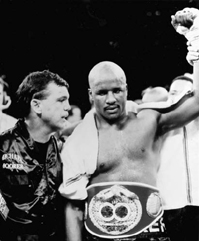

In the ring at Caesars Palace as Michael Moorer has his hand raised by the referee after beating Evander Holyfield and winning the world heavyweight title in 1994.

Twenty thousand people came out for the victory parade in Michael Moorer's hometown of Monessa, Pennsylvania, in 1994. Manager John Davimos and I hold the two world title belts won in the fight against Holyfield, while Michael sits between us.

Me and Willem Dafoe training in Gleason's Gym in 1988 for his role as a concentration camp boxer during World War II in the film

Triumph of the Spirit

.We later trained in Auschwitz and Birkenau.

My family. Me, Nicole,Teddy III, and Elaine, at an awards dinner in Manhattan, where they recognized the foundation for the work it does, and presented us with the N.F.L. Helping Hands Award, in 2000.

A

S SOON AS WE GOT UNPACKED AND SETTLED IN MY

parents' basement apartment, I went to a gym in Brooklyn above the Walker Theater, where my friend Nick Baffi was working. Nick was an old friend of Cus's who I'd met in Catskill during my time there. When he heard I was moving back to the city, he told me to come by.

Pretty quickly I found a couple of guys to train thereâor, to be more exact, they found me. One of them was Johnnie Verderosa, who was trying to launch a comeback. I knew Johnnie from when we were kids in Staten Island. I'd sparred with him and helped him get into shape when he was training for the New York Golden Gloves. He'd always been appreciative of the fact that I made some sacrifices to do that.

Johnnie was a little guy, 130 pounds soaking wet, but a hell of an athlete. His father was an alcoholic. I remember that there was always a garbage pail full of beer in the kitchen of their house. Johnnie had these older brothers, Guy-Guy and Tom-Boy, who became drug addicts and were in and out of Rikers. As a result of growing up with them, and seeing what they were, Johnnie stayed away from drugs and alcohol. He was very hard-line about it; he wasn't going to be like them. He wouldn't

hang out on the corner or go to bars. We always understood why, that he had his head on straight.

“I'm taking care of my body,” he'd say. His addiction was sports. Football. Baseball. Boxing. Especially boxing. He was tough and had a lot of heart. He won the New York City Golden Gloves two times, and then turned pro and became the USBA super featherweight champ. He got written up in

Ring

magazine along with Boom Boom Mancini. A lot of people, his mother in particular, were proud of him.

Then, just like that, just when he was in that position, and it seemed like his discipline and hard work were paying off, he began doing cocaine, and doing it openly, doing all the things he said he was never going to do. It was baffling. On the verge of real success, he took this 180-degree turn. I don't know if it was guilt that he was leaving his brothers behind or if all that discipline was finally too exhausting. I just know you can drive yourself crazy trying to figure out stuff like that.

When his manager approached me, it was after drugs had already dragged down his career, and he was trying to revive things. He asked me if I would help him. I agreed, provided he stayed clean. I knew it wasn't an easy thing for him, so I had him stay with us, with me, Elaine, and the baby, at the house, so he could have that support. I gave him a curfew and stayed on top of him. It worked. He got into shape, and won a couple of fights.

Then, right before his third fight, he came home one night while I was out training another fighter. He told Elaine not to tell me, but he was going back out. When I got home, I asked her where he went, and she didn't know. I knew something was up. I went driving around the neighborhood to all his old haunts, trying to track him down. I walked into this one bar where I heard he sometimes used to go to cop cocaine. I went up to the bartender and asked him if Johnnie Verderosa was around. He said, “No,” but I knew it was a lie because he was nervous. I saw his eyes dart over to a corner of the room. In the reflection of the mirror behind the bar, I saw Johnnie cowering on the floor behind a pinball machine. As mad as I was, I didn't say anything. I just walked out as if I hadn't seen him.

About midnight that night, he came home. I was up, waiting. I didn't waste any time; I got right to the point.

“I saw you,” I said. “I know what's going on.” I didn't have to say anything else. He knew why I hadn't said anything earlier, that I hadn't wanted to embarrass him.

“You don't have the discipline it takes to be a fighter anymore,” I said.

He didn't argue. He didn't fight with me. His head was down. He was ashamed. He said, “I'm sorry. You took me in and I let you down. I betrayed you.”

“No, you betrayed yourself,” I said.

This was a kid I'd had living under the same roof with me and my family. A kid who'd told me how much it meant to him not to have to sleep with cotton in his ears, which he'd had to do where he'd been staying before so the cockroaches wouldn't go in his ears. I'd been training him and feeding him and really trying to straighten him out. It tore me up to see him slip back. Even though it was something I thought I understood a little from my own life, maybe I didn't understand it as well as I wanted.

Johnnie went and fought his next fight without me and got knocked out. He called me a few times after that and asked me for money. I gave him a twenty here and there. I had real feeling for him, but it was just weakness on my part to give him money. He'd tell me it was for food, but I knew it was for drugs. So the next time he asked, I said, “I ain't giving you a cent. If you want something to eat, if you're hungry, I'll sit with you. I'll take you to a diner and buy you dinner. But I ain't givin' you no money. I'll take you to a drug rehab. I'll help get you in, and when you're allowed a visit, I'll come visit. Or if you're not allowed a visit, I'll write. Whatever it takes to make you feel a connection.”

The thing is, even with the drug problem, Johnnie was a good kid. There was something about him that I liked. With all his problems, he never hurt anyone else or blamed anyone but himself. I appreciated that. He had character even though he had a weakness. His boxing career ended after the knockout; he retired after that, but eventually, after drifting for a few years, he straightened himself out. He found a girl, he started working construction, and from what I understand, at least the last I heard a few years ago, he was in a decent place.

After the break with Johnnie, I started going to the old Gleason's Gym, over on Thirty-first Street between Seventh and Eighth. I'd take

the ferry and the subway, and go in there every day. I was still at a point in my career where I was doing spade work, digging up holes, planting seeds, hoping things would grow. I got a few amateurs, and I was working with them. It was just like Catskill, working all day, making no money, trying to turn these guys into fighters. They weren't the right guys yet. I was just putting in the time, working my trade, improving as a trainer.

Ira Becker, who ran Gleason's, knew what I was; he knew my background, that I had worked with Cus. He thought I had some talent. This was in the early 1980s, when the whole white-collar boxing craze was beginning. These Wall Street guys were showing up at Gleason's, paying good money to learn how to box. A lot of them wanted to work with me, but I always rejected them.

Truthfully, it wasn't smart on my part. It didn't make financial sense to say no. But I was coming from a place, having worked with Cus, that I was a professional trainer who would make world champions, and that there was a purity to what I was doing. You grow up, you get over that kind of thinking. You realize that you don't have to compromise yourself to make money along other avenues, that it's okay and can even be another level of your trade, teaching and developing guys who would normally never have a clue or a chance in that world. But that's the way I thought then. I was the Young Master, and I was fulfilling my destiny. It didn't include these white-collar guys. Ira Becker used to come up to me and say, “Teddy, do me a favor. Can I talk to you? Why don't you take some of these guys?” I understood where he was coming from. These guys were asking for me, and I was rejecting them, and he wanted their membership, he didn't want to lose them. He said, “Listen, there's this Spanish guy that trains ten guys in a class each morning and makes a hundred and fifty dollars. You could get three hundred dollars easy.” I should have done it. I was living in my parents' basement. I had an infant daughter. There were plenty of good reasons. But I kept saying no. It was just a way of thinking that I was stuck in.

One day this guy I knew there, Rudy Greco, an attorney who was involved in the boxing business, came up to me and said, “I have an interesting proposition for you. Do you know who Twyla Tharp is?”

“No.”

“She's the Muhammad Ali of dance. I just got a call from somebody

that she needs to get back in shape to dance. She's decided she wants a boxing trainer, and your name came up. I think you should do it.”

“I ain't training no ballet dancer,” I said.

“Teddy, do me a favor, just talk to her.”

He started telling me more about her, that she was this famous dancer and choreographer who had done the musical

Hair

on Broadway and a bunch of other things. Being a lawyer, he made a good case. The truth is, Rudy knew my situation financially, and he was looking out for me. His persuasiveness plus the thirty-five dollars an hour I stood to make got me to agree to talk to her.

Tharp called a couple of days later. I made an appointment to meet her.

I still had the keys to the Walker Theater in Brooklyn, Nick Baffi's gym, and I met her there. She was both grateful and apologetic. She kept saying, “I know this all must seem a bit silly to you. I'm a dancer, and you're a boxing trainer.” At the same time, she told me how sincere she was about undertaking this. She was very gracious and humble. It was smart of her. She won me over.

Right off the bat, she asked me lots of questions about the philosophy of boxing, and I told her about dealing with fear, controlling emotions, and how those were things that could be transferred to other disciplines. It appealed to her. She was forty-four, which was old for a dancer, and she was getting ready to perform for the first time in a while. She had a lot of pride, ego, and professionalism, and she wanted to be in better shape than she had been when she was in her twenties, if that was possible.

I told her it was. “I'm willing to teach you boxing for two reasons,” I said. “One, so you can have the ability to undertake a physical regimen with it, which entails learning enough technique so that you can get the benefits of this workout. Two, so that you can learn how to go into dark places and not get broken down. I think that would help you. If you can learn a bit of the discipline that fighters learn, you can take that onto the stage with you.”

She loved that kind of thinking, that kind of philosophy. She was into yoga and all that stuff. This was yoga with a punch. I created a training program for her. I made her run up and down the steps in the Walker Theaterâand there were a lot of steps. I had her skip rope, shadowbox, do push-ups, kick-outs, sit-ups, everything I'd have my fighters

do. I ran her ragged, and she dealt with all of it and never complained. You could see why she was successful. She had a capacity to work extremely hard.

The first time I had her slip a punch, I said, “Listen, I'm going to throw a punch at you. Now athletically I know how talented you are, and the move you need to make is obviously something you can do, but there are other elements involved.” As I explained the mechanics of moving her upper torso, and how she might instinctively want to turn away but would have to resist doing so, she began to smile.

“Why are you smiling?” I asked.

“Because it's so simple. I'm a dancer. I make moves like that all the time.”

“Yeah? You think it'll be easy? I'll make you a bet right now,” I said. “That when I throw a punch you can't do it.”

“Okay.”

I told her to put her hands up, and when I threw the punch, she jerked back from it.

“Wait a minute,” she said. “Let's try that again.”

Now I was smiling. I threw another punch. Again, she turned away from it.

“What happened, Twyla?” I said. “I thought it was a simple move.”

She pretended to get all huffy and said, “You're not treating me like a lady, Teddy.”

“It's interesting, isn't it? You know I'm not really going to hurt you, but just the idea of my punch, the danger it represents, is enough to screw you up. That shows you where we're going. Learning to contain that emotion. Not to pull back. Not to close your eyes. But to face what you have to face and slip the punch. This isn't about anything but the physical action. You're not thinking about avoiding getting hit, or worrying about being hurt, you're just focused on the action of the move. This isn't so you can become a prizefighter, but so you can become a better pro. So you're better equipped to deal with anxiety and fatigue and fear onstage.”

She understood and she learned. Pretty soon, I had her slipping punches. She got good. Then I had her on the hand pads, and I was throwing punches at her more freely. One time, though, she didn't move, and I hit her. She got a black eye. She wouldn't put makeup on or

anything. I felt a little bad. She said, “Are you kidding me? I'm gonna make sure everyone sees this.” I heard later that her dancers began calling her “Boom Boom” Tharp.

At the other end of the spectrum, when I wrapped her hands for her, she said, “Remember, I am a lady and I like these nails. It's important for my hands not to look like a fighter's. Anything else, fine, but make sure my hands are protected.”

“Don't worry,” I'd say. “Your nails will still be beautiful when I take the gloves off.”

“You sure?”

“I'm sure.”

We worked five days a week for nearly a year, and she got into great shape. At a certain point we moved out of the gym and I began training her at the American Ballet Theatre. Right on the polished wooden floors. When her dancers started arriving at the studio, toward the end of our session, she introduced me to them. She was both sweet and self-deprecating. “This is Teddy Atlas, who has allowed me to take up a little space in his world, even though I embarrass him.” Afterward, she asked me to stay and watch her rehearse her company, in part, I think, because she wanted me to see what she was like when she was giving orders, not taking them.

Twyla took some of the moves she learned from me and put them into one of her dance pieces. I don't know if she had that in mind before the training, but she made this piece called “Fait Accompli,” using boxing movement. When it premiered in November 1983, she flew me and Elaine down to Washington. We got all dressed up and went to opening night at the Kennedy Center. We were sitting in the front row, and you know the kind of people who go to these thingsânot the fight crowdâand right behind us, when Twyla came onstage for the first time, this guy exclaimed, “My God, she looks like a champion fighter!”