Austerity Britain, 1945–51 (92 page)

Read Austerity Britain, 1945–51 Online

Authors: David Kynaston

Eliot and Fry were the two key figures in a new movement – a movement initiated by the latter’s

The Lady’s Not for Burning

, a huge West End success in 1949 (featuring Claire Bloom and Richard Burton in supporting roles). ‘In a post-war theatre that had little room for realism,’ noted Michael Billington in his 2005 obituary, ‘Fry’s medieval setting, rich verbal conceits and self-puncturing irony delighted audiences, and the play became the flagship for the revival of poetic drama.’ Anthony Heap, a dedicated first-nighter, was not a fan. Labelling Fry as ‘that current darling of the quasi-highbrows and pseudo intellectuals’, he described in his diary in January 1950 attending the premier of Fry’s next play,

Venus Observed

: ‘As the evening wore laboriously on, it became increasingly apparent that . . . Mr Fry’s new blank verse effusion bore a closer resemblance to its predecessor . . . than it did to a play, being equally devoid of genuine dramatic interest.’ Gladys Langford, going to the St James’s Theatre a day or two later, agreed: ‘Oh, what a welter of words! Oh, what an absence of action!’ Soon afterwards, Mollie Panter-Downes noted how the play (starring Laurence Olivier) was proving ‘a smash box-office hit’ despite or perhaps because of receiving ‘bemused notices from most of the critics, who professed themselves entranced, though whacked by what it was all about’. She reflected on how the play showed ‘all Fry’s bewildering, glittering gift for language, unfortunately mixed with a deadly facetiousness that at its worst makes his lines sound like a whimsical comedian’s double-talk’.

May saw the West End premier of Eliot’s

The Cocktail Party

, which, notwithstanding Heap’s hostile verdict – ‘Do poets who write plays

have

to be so damnably enigmatic? Or is that just their little joke?’ – went on to enjoy a considerable vogue. Early in 1951, some two months after Lawrence Daly had fallen asleep listening to

Venus Observed

on the radio, the

New Statesman

’s perceptive drama critic, T. C. Worsley, sought to contextualise the apparently irresistible rise of verse drama:

What we have seen is the development in the theatre-going public of a new hunger for the fantastic and the romantic, for the expanded vision and the stretched imagination, in short for the larger-than-life. This is easily explainable as a natural reaction from the sense of contraction which pervades at least the lives of the middle classes; and it is still the middle classes who make up the bulk of the theatre-going public.

‘If they are finding that they can afford to do less and less,’ he concluded with an obligatory sneer at these suburbanites, ‘it at least costs no more to please the fantasy with extravagances than to discipline it with dry slices of real life.’

27

Even so, and whatever the merits or otherwise of this latest fashion, it is difficult to deny the generally sterile, unadventurous state of the British theatre by the early 1950s. It did not help that the Lord Chamberlain continued to exercise his time-honoured powers of censorship over the precise content of plays. Nor was it helpful that the H. M. Tennent theatrical empire, run from an office at the Globe in Shaftes-bury Avenue by Hugh (‘Binkie’) Beaumont, possessed close to a stranglehold over what was and was not performed in the West End. Beaumont’s standards were high, with a penchant for lavishly mounted classic revivals as star vehicles. Typical productions in 1951 included Alec Guinness in

Hamlet

; Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in

Antony

and Cleopatra

and

Caesar and Cleopatra

on alternate nights; Gladys Cooper in Noël Coward’s

Relative Values

; Celia Johnson and Ralph Richardson in

The Three Sisters

; and John Gielgud and Flora Robson in

The Winter’s Tale

. What there was virtually no encouragement for was drama that dealt with contemporary issues. Arguably one of the few playwrights to do so was the immensely popular Terence Rattigan – but only in the sense that his work tapped so deftly into the anxieties and neuroses of the economically straitened post-war middle class. Rattigan himself wrote in 1950 a famous essay denouncing what he called ‘the play of ideas’ and declaring that ‘the best plays are about people and not about things’.

28

It was a proposition that, as ‘Binkie’ would have agreed, made commercial sense.

If there was one play that epitomised – for good as well as ill – British theatre before the revolution, it was perhaps N. C. Hunter’s

Waters of the Moon

. Norman Hunter was a Chekhov-loving retired schoolmaster and obscure playwright; his play, taken up by Beaumont, was set in a shabby-genteel hotel on the edge of Dartmoor, and the first night, with Edith Evans (in evening gowns designed by Hardy Amies), Sybil Thorndike and Wendy Hiller all in leading roles, backed by Donald Sinden as assistant stage manager, was on 19 April 1951 at the Haymarket. An ‘enchanting bitter-sweet comedy’, thought Heap, ‘richly endowed with acutely observed and sympathetically drawn characters’. And, he predicted, ‘It is the kind of play that has cast-iron, box-office success written all over it.’ The critics were on the whole friendly, with Worsley again on the money. Although finding

Waters

a play unworthy of ‘our incomparable Edith Evans’, he reckoned that it ‘will, all the same, find a large public, the public which so enjoyed Miss Dodie Smith’s plays before the war’. He observed that although Hunter had ‘added to the formula some rather crude borrowings from the Russians’, his play remained ‘essentially a cosy middle-brow, middle-class piece, inhabited by characters by no means unfamiliar in brave old Theatreland’ – including ‘the maid-of-all-work daughter of the house’ (Hiller) and ‘a lost relic of the poor, dear upper-middle-classes’ (Thorndike).

Worsley and Heap guessed right: the play ran for more than two years and grossed more than £750,000. But for Hunter, despite a couple of reasonable successes later in the fifties, the tide would go out almost as quickly as it had come in, and he died in 1971 a semi-forgotten figure. Seven years later, the Haymarket staged a revival of

Waters

, with Hiller returning to the fray. The theatre management, trying to keep a lid on costs, asked the playwright’s Belgian widow Germaine whether it would be acceptable to pay a reduced author’s royalty. Germaine, through a spiritual medium, consulted Norman, and Norman replied that it would not.

29

‘I almost immediately began to cry,’ wrote Gladys Langford in north London on the first Monday of April 1951. ‘The climbing of steps, the squalor of some of the households, the inability to get a reply & the knowledge that I should have to retread the streets again and again, reduced me to near hysteria.’ She was working as a paid volunteer for that month’s Census – the first for 20 years and inevitably the source of much relevant data, most especially about housing conditions.

Out of a total of 12.4 million dwellings surveyed in England and Wales, it emerged that 1.9 million had three rooms or less; that 4. 8 million had no fixed bath; and that nearly 2.8 million did not provide exclusive use of a lavatory. Overall, in terms of the housing stock, almost 4.7 million (or 38 per cent) of dwellings had been built before 1891, with some 2.5 million of them probably built before 1851. Put another way, the great majority of houses in 1951 without the most basic facilities had been put up by Victorian jerry-builders. The Census, moreover, revealed a significant quantitative as well as qualitative problem: although the official government estimate was that the shortage was around 700,000 dwellings, the most authoritative subsequent working of the data would produce a figure about double that.

1.

Of course, it was hardly news that there was a housing problem, but the Census reinforced just how severe that problem was.

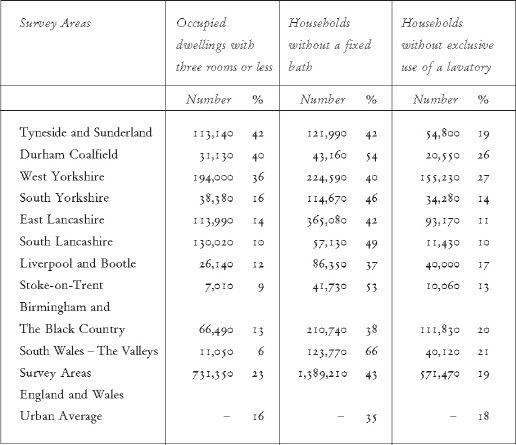

Naturally there were major regional variations, even between the large urban areas where most of the substandard housing was concentrated. The following table, derived from the Census, gives the broad picture outside London and Scotland:

Between the autumn of 1949 and that of 1950, a sociologist, K. C. Wiggans, surveyed living and working conditions in Wallsend, the shipbuilding town near Newcastle upon Tyne from which T. Dan Smith came. Most of the men surveyed lived in the riverside district, consisting ‘almost entirely of old houses, many of them condemned and overcrowded’. Wiggans highlighted one man, who ‘said that he, and eight others, were occupying a four-roomed upstairs flat, consisting of two bedrooms, a boxroom and a kitchen’:

The subject and his wife, a son aged eight, and an unmarried daughter of eighteen slept in one room; a married son, wife and child, aged two, slept and lived in another, whilst a son, aged twenty-one, slept in the kitchen, and an old grandfather had the box room. There was no bath, no hot water, no electric light and the lavatory was down in the backyard. The ceilings and walls of the house were rotten with damp; in wet weather the rain streamed through the roof, with the result that no food could be stored for more than a day or two without going bad.

‘A very large proportion of the houses which were visited in this area,’ added Wiggans, ‘had these particular problems, to a greater or lesser degree.’

Soon afterwards, John R. Townsend visited for the

New Statesman

the ‘huge, crazy entanglement of sooty streets sprawling over the southern half of Salford, from Broad Street to the Docks’. Focusing particularly on Hanky Park, the district that had been the setting for Walter Greenwood’s

Love on the Dole

, he found ‘a fair, perhaps slightly worse than average, specimen of a northern city slum’:

Blackened, crumbling brick, looking as if only its coating of grime held it together; streets so narrow that you need hardly raise your voice to talk to your neighbour across the way; outdoor privies in odorous back entries; dirt everywhere, and no hot water to fight it with; rotting woodwork which doesn’t know the touch of fresh paint; walls which often soak up the damp like blotting-paper – in short, nothing really exceptional.

In Salford as a whole, out of the city’s 50,000 houses, no fewer than 35,000 were more than 60 years old, with the overwhelming majority having neither bath nor hot water. Would things change? After noting how in 1948 some Salford schoolchildren had been asked to write ‘about where they would really like to live’, with many expressing ‘wild longings to be away from Salford, in reach of the country, the sea, the mountains’, Townsend concluded pessimistically: ‘As things are shaping at present, it is hardly more than a hope that their children’s own children will avoid being born and bred in the back streets.’

2.

The housing situation was even worse in Scotland, where in 1950 it was estimated that around 1.4 million out of a population of some five million were ‘denied a reasonable home-life’ through having to endure overcrowding, squalor, lack of sanitation and so on. Glasgow above all remained a byword for dreadful housing. The 1951 Census revealed that a staggering 50.8 per cent of the city’s stock comprised dwellings of only one or two rooms, compared with 5.5 per cent for Greater London; while in terms of the percentage of population living more than two per room, the respective figures were 24.6 and 1. 7. Overall, Glasgow’s residential density in 1951 was 163 persons per acre – compared with 48 for Birmingham and 77 for Manchester, both of which English cities thought with good reason that they had major housing problems. Probably nowhere in Glasgow was the squalor greater than in the Hutchesontown district of the Gorbals. There the density was no fewer than 564 persons per acre, with almost 89 per cent of its dwellings (often part of pre-1914 tenements) being of one or two rooms, usually with no bath and frequently with no lavatory of their own. For Glasgow as a whole, it was reckoned by the early 1950s that as many as 600,000 people – well over half the city’s population – needed rehousing.

3.

It was a daunting (if to some invigorating) statistic.

The majority of housing in the Gorbals was in the hands of private landlords, as in 1951 it was in the case of 51 per cent of the stock in England and Wales (compared with 57 per cent in 1938). Rented housing was, in other words, the largest single sector of the market, and it was a sector in deep, long-term trouble.

‘Never receiving any “improvements”, never painted, occasionally patched up in the worst places at the demand of the Corporation’ – such was the reality in 1950 of the privately rented housing that dominated the Salford slums. For, as Townsend explained:

Owners say that on the present rents they cannot afford to pay to keep their property fit for habitation, and it is a fact that many of them will give you whole streets of houses for nothing, and ten shillings into the bargain for the trouble of signing the deeds, if you are stupid enough to do so. Some owners have merely disappeared without trace, leaving the rents (and the repairs) to look after themselves until the Corporation steps in.

Soon afterwards, a senior Glasgow housing official confirmed the trend: ‘Forty years ago there were many empty houses but few abandoned by their owners. Today there are no empty houses yet many have been abandoned by their owners.’

4.

There were two principal reasons why the private landlord was, in some cities anyway, in almost headlong retreat. Firstly, a welter of rent-control legislation, going back to 1915 and involving a freezing of rent levels from 1939, was indeed a significant deterrent. ‘Before the war, people were willing to pay between one-quarter and one-sixth of their income on rent,’ noted the

Economist

’s Elizabeth Layton in 1951. ‘Now they are not so prepared because they have become accustomed to living cheaply in rent-controlled houses and do not appreciate that, while incomes have increased, rents have lagged behind what is required to keep old property in repair or to cover the annual outgoings of new houses.’ Undoubtedly at work was an instinctive, widespread dislike of the private landlord, and this sentiment particularly affected the second reason for the rented sector’s difficulties: namely, government reluctance to help much when it came to making grants for improvements and repairs. Bevan’s 1949 Housing Act did offer the promise of some assistance, but he was not a minister ever likely to embrace the landlord as one of his great causes. The hope – at least on the left – was that sooner rather than later huge swathes of urban slum clearance would in the process come close to finishing off the private landlord altogether.

Not all rented housing was wretched, but it does seem that precious little of it was conducive to the good life. Away from the out-and-out slum areas, perhaps fairly typical of these immediate post-war years was the situation in which the Willmotts (Peter, Phyllis and baby son Lewis) found themselves in the early 1950s. Desperate for somewhere to live on their own, they landed up in Hackney, occupying (in Phyllis’s words) ‘the top two floors of a plain, yellow-brick Victorian house hemmed in on three sides by streets’, including a main road to Dalston Junction. They had two rooms and a kitchen on the first floor, and a large room on the floor above, but it was still a pretty dispiriting experience:

The stairs were meagrely covered with well-worn lino; kitchen, bedroom and hall were painted in nondescript shades of beige, and in our sitting-room there was a depressing patterned wallpaper of pink and brown ferns. The landlord was proud of these decorative features and made it clear that he would not permit any changes to them . . . We had the use of the bath in the kitchen of the ground-floor tenants. We seldom exercised this right because it was too much trouble to fix a convenient time (and I was afraid of the explosive noises made by the very old geyser). We had to make do with hot water from a gas heater that the landlord allowed us to install over the kitchen sink – at our own expense. There was one shared lavatory on the ground floor, and shared use of the neglected patch of ground that could hardly be called a back garden but could be used to hang out the washing by tenants.

It was much the same for another young family in Swansea. ‘It is a ground-floor flat in an ill-built house, rather too small and with no room to put anything,’ Kingsley Amis wrote to Philip Larkin in December 1949 from 82 Vivian Road, Sketty, Swansea, which for the previous few weeks had been home for himself, his wife Hilly and two small children, including the infant Martin. ‘There are fourteen steps between the front-door and the street, and most of the time I am carrying a pram or a baby up or down them.’ Over the next year, the Amis family lived in three other rented places, including two small flats on Mumbles Road, before in early 1951 a small legacy enabled them to buy a house. ‘These were primitive places with shared bathrooms and in one case an electric cooker that guaranteed shocks for the user,’ notes an Amis biographer; he adds that they were the model for the Lewises’ flat in

That Uncertain Feeling

(1955) – a novel in which the Amis-like hero is in a state of perpetual guerrilla warfare with the censorious, small-minded Mrs Davis on the ground floor, where she converts her kitchen door ‘into an obstacle as impassable as an anti-tank ditch’.

5.

The growth area in housing by this time was undoubtedly the local-authority sector, a trend strongly encouraged by the Labour government. The figures alone tell the story: 807,000 permanent dwellings were built for local authorities between 1945 and 1951, compared with 180,000 for private owners. And the 1951 Census showed that, in England and Wales, 18 per cent of the housing stock was in the hands of local authorities – an increase of 8 per cent on 1938. As before the war, much of this new public housing was designated for lower-income groups, with councils expected to let it at affordable rents, but Bevan was determined that it should be of sufficient quality to attract the middle class as well in due course. Significantly, his 1949 Housing Act enshrined the long-term provision of local-authority housing for ‘all members of the community’, not just ‘the working classes’. This was not quite such a fanciful aspiration as it would come to seem, given that it has been estimated that in 1953 the average income of council-house tenants was virtually the same as the overall average income – a reflection in part of how most of the real poverty was concentrated in privately owned slums, in part of how predominantly working-class a society Britain remained.

6.

And of course, there was for most activators (whether national politicians, local councillors, civil servants, town planners or architects) a powerful urge to put public housing at the heart of the New Jerusalem.