Austerity Britain, 1945–51 (89 page)

Read Austerity Britain, 1945–51 Online

Authors: David Kynaston

My grasp of what was going on was even weaker than with Class 2. All I knew was that when I came through the door they rose and dreadful remarks filled the air.

‘Hiya, mister!’

‘Here he is, boys. Give him the works!’

‘What’s this? A teacher?’

‘Let’s give the bloke a song!’

Then would follow a dizziness of howls and improbable acts.

‘All right,’ I would shriek, ‘I’ll give you some very hard arithmetic’.

Boys would rush to the front. ‘You’ll want paper, sir.’ ‘Get Mr What’s-’is-name some paper.’ ‘Blackboard, sir?’ ‘Up with the blackboard for Mr What-d’ye-call-’im.’ And I would watch, fulminating uselessly, while a dozen self-selected blackboard erectors struggled with the easel in an ecstasy of mischief that left the Marx Brothers standing. The rest would be at the cupboard, gleefully flinging its contents into mad confusion, snatching at paper until it flew in a snowstorm through the air. ‘All stand!’ I would yell. And, cheering, they would struggle to their feet; then, shouting ‘All sit!’ they would crash their bottoms down again on the benches. There were times when I could hardly believe the evidence of my eyes. Were the Police, the Armed Forces, the Government itself, aware that events of this nature could occur in one of the country’s schools before a trained teacher on probation?

Remarkably, Blishen stuck it out as a secondary modern teacher until 1959. ‘The battle had already been lost outside the school’ began his bleak but humane assessment more than three decades later. ‘They’d come already hugely discouraged – so discouraged that most of them had not even entertained the idea of making any use of schooling of any ambitious kind at all. Many of them had become by the age of eleven or twelve so tired of the whole grind of schooling. They’d seen so much teaching which seemed to them to be grudging.’ Or, as he concluded: ‘Most of the boys knew that the system didn’t really care about them and wasn’t really bothered if they did badly.’

11

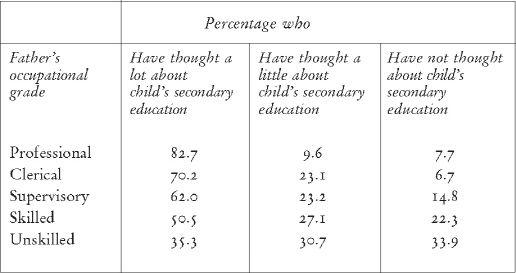

As for parental attitudes, the first systematic study of their preferences in secondary education was undertaken in 1952 by F. M. Martin in south-west Hertfordshire, in effect Watford and its environs. Printing and precision engineering characterised the local economy, with little heavy industry; manual workers made up two-thirds of Martin’s sample of 1,446 parents of children eligible for that year’s 11-plus. There emerged a clear correlation between class and attitude:

When it came to preferred types of secondary school, the percentages were also predictable, with 81.7 per cent of parents from the professional category expressing a preference for a grammar school but only 43.4 per cent from the unskilled group; similarly, 70.2 per cent of professionals thought that the move to secondary school would ‘make a lot of difference’ in their child’s life, compared with 40.8 per cent of unskilled parents. Tellingly, of those parents expressing a preference for a grammar school, only 43.5 per cent of professionals were willing to accept a place in a secondary modern, compared with 75.5, 89.4 and 94.7 per cent of supervisory, skilled and unskilled workers respectively.

12

The obvious alternative was a private, fee-paying school outside the state system. Here Martin found that whereas 49.4 per cent of professionals for whom a grammar school was the first choice were if necessary willing and able to countenance that route, such a course potentially applied to only 1.5 per cent of unskilled workers. By the early 1950s most private schools were fully subscribed – educating some 180,000 out of a total of 5.5 million children – and as ever there was a mixture of motives involved, including socio-cultural as well as economic and educational ones. ‘Yafflesmead is rather like home on a larger scale,’ Mrs J. R. Luff (living in Haslemere and married to a businessman) explained to

Picture Post

in 1950 about why they had chosen a private school in Kingsley Green, Sussex. ‘It is cosy, no long corridors, no bleak classrooms. The children whom Helen [eight] and Andrew [five] meet there, all have the same kind of background and do not have constantly to adjust themselves to different standards.’ For the Rev. J. W. Hubbard, who lived in South Walsham near Norwich, sending his 13-year-old son to a boarding school in Harpenden was all about exercising freedom of choice in the best possible cause: ‘I want my children to have a “good” education. Not only proper teaching, but also to learn good language, nice manners. As the Junior State schools are run at present, with their overcrowded classrooms, I do not think they can offer a suitable training in all ways as a private school. I’m sure Laurence has a better chance of getting to the university and of becoming a fully developed person if he is educated at St George’s.’

13

Even setting aside the question of private education – obviously feasible only if it could be afforded – the Hertfordshire survey does suggest an appreciably more fatalistic working-class approach to education: taking what was on offer, and in many cases not even contemplating the possibility of anything better. Clearly there were exceptions, perhaps exemplified by Tom Courtenay’s mother, who was keenly aware of the advantages – intellectual as much as material – that a grammar-school education potentially offered. Yet at least as typical in the early 1950s may have been the hostile attitude of the bricklayer father of Bill Perks (later Wyman), who abruptly pulled his son out of Beckenham Grammar School shortly before O levels. ‘He’d found me a job working for a London bookmaker,’ recalled Wyman. ‘There was a big future for me there he said, and eventually, with my expertise at figures, he could open his own betting company. I was dumbfounded, but had no say in the matter.’ The headmaster tried to get Wyman’s father to change his mind, but he was unbending. Having to leave school ‘was a bitter blow to my confidence’.

Among most working-class parents of children at secondary moderns, the impatience with education was far more pronounced – an impatience fully shared by their offspring. ‘The school-leaving age had been raised to fifteen two years before,’ noted Blishen’s narrator of his first term’s teaching:

This was still a raw issue with most of the boys and their parents. They felt that it amounted to a year’s malicious, and probably illegal, detention. Nothing in the syllabus as yet appeared to justify that extra year. And to justify it to some of these boys would have required some scarcely imaginable feat of seduction. We teachers were nothing short of robbers. We had snatched a year’s earnings from their pockets. We had humiliated them by detaining them in the child’s world of school when they should have been outside, smoking, taking the girls out, leading a man’s life . . .

Preventing any further postponement to raising the school-leaving age (specifically envisaged in the Butler Act) had been Ellen Wilkinson’s great achievement shortly before her death in February 1947, an achievement that had owed much to her impassioned appeal to fellow-ministers that it was the ‘children of working-class parents’ who most needed that extra year of education after the interruptions of wartime. But for those actual children and their parents, the cheering was – and remained – strictly muted.

14

The pioneering survey of how the 1944 Education Act was playing out in socio-economic practice was conducted by Hilde Himmelweit in 1951. Her sample comprised more than 700 13- to 14-year-old boys at grammar and secondary-modern schools in four different districts of Greater London. In the four grammars, she found that whereas ‘the number of children from upper working-class homes’ had ‘increased considerably’ since 1944, ‘children from lower working-class homes, despite their numerical superiority in the population as a whole, continued to be seriously under-represented’ – constituting ‘only 15 per cent of the grammar school as against 42 per cent of the modern school sample’. In those grammars, the middle class as a whole took on average 48 per cent of the places and the working class as a whole 52 per cent (more than two-thirds by the upper working class). In the four secondary moderns, by contrast, the middle class averaged 20 per cent of the places, the working class the other 80 per cent.

Himmelweit then demonstrated how the apparent parity between the middle and working classes at the grammar schools was deceptive – not only in the obvious sense that the middle class comprised far fewer than 48 per cent of the overall population and the working class far more than 52 per cent but also in terms of how the middle-class boys consistently outperformed the working-class boys academically. ‘The results show that, in the teacher’s view, the middle-class boy, taken all round, proves a more satisfactory and rewarding pupil. He appears to be better mannered, more industrious, more mature and even more popular with the other boys than his working-class co-pupil.’ Furthermore, as a correlation, ‘Parents’ visits [ie to the schools] increased with the social level of the family and decreased with the number of siblings. Middle-class parents were found more frequently to watch plays and sports.’ Unsurprisingly, in these grammar schools far more working-class than middle-class boys expressed the wish to leave before going on to the sixth form, often adding that this was what their parents wanted. Yet simultaneously, 78 per cent of the working-class grammar boys, compared with 65 per cent of the middle-class boys, ‘regarded their chances of getting on in the world as better than those their fathers had had’.

15

There was, in other words, a marked discrepancy between aspirations and daily conduct. Himmelweit herself refrained from drawing out any ambitious conclusions from her survey, but it was clear that there was still a long way to go before the existing system of secondary education significantly dissolved entrenched class divisions and very different life chances.

Indeed, it was an egalitarian urge that largely lay behind the hardening rank-and-file mood in the Labour Party by the early 1950s in favour of comprehensive education, with a view to abolishing the divide between grammars and secondary moderns. By the summer of 1951, following intensive pressure from the National Association of Labour Teachers, this was official party policy – but it did not mean that most Labour ministers agreed with it. As Minister of Education since early 1947, George Tomlinson had consistently upheld the primacy of the grammar school and did little to encourage those backing the comprehensive or ‘multilateral’ alternative. With few exceptions, he either blocked, delayed or watered down the various proposals for new comprehensive schools that came across his desk. He was much struck by the way in which support for comprehensives had proved a vote-loser for Labour at the Middlesex County Council elections in 1949; and, as he frankly if privately put it in early 1951, ‘the Party are kidding themselves if they think that the comprehensive school has any popular appeal.’ Most Labour local authorities, certainly outside Greater London, were similarly cautious. Even in Coventry, which in 1949 came down decisively in favour of comprehensives, the move has been convincingly attributed far less to ideology than to such practical considerations as ‘post-war accommodation, overcrowding, the poor quality of the buildings and the demand for secondary school places from the local population’.

Across England and Wales, the overwhelming force in the early 1950s was still with the actual grammars rather than the notional comprehensives, hardly any of which yet existed. The grammars enjoyed enormous prestige, both locally and nationally. There persisted a widespread, understandable belief that they provided a unique – and, since 1944, uniquely accessible – upwards social escalator for the talented and hard-working; there was a desire to give secondary moderns, the other side of the coin, time to prove themselves; the necessarily large size of London’s planned comprehensives, involving a roll of more than 2,000 children in each (in order to achieve a viable sixth form) as opposed to the 800 or so of the average grammar, was a major drawback to those indifferent to the egalitarian aspect; and, of course, the Burt-led orthodoxy about intelligence testing still held almost unchallengeable sway.

16

Inevitably, the challenge of educating a new, post-war generation was much on people’s minds. It was certainly on the mind of the writer and journalist Laurence Thompson, who between the autumn of 1950 and the spring of 1951 travelled the country to produce

Portrait of England

– subtitled

News from Somewhere

in homage to William Morris, whose

News from Nowhere

had predicted 1952 as, in Thompson’s words, ‘the year of revolution from which Utopia sprang’. In London he was told that as many as a quarter of pupils at grammar schools were removed by their parents at 15 in order to enter the labour market; in Manchester he visited several schools; and elsewhere he was told by a chief education officer of how the situation looked on the frontline. ‘Ten per cent above average, fifty to sixty per cent average, and the rest can’t really benefit from anything we teach them,’ declared his battle-hardened witness. ‘The proportions will always be the same, and the problem will always be that below-average minority. All we can hope to do is to swing them over into reasonably decent citizens.’ One of the schools Thompson visited in Manchester was a primary, where he was shown ‘some extempore prayers’ written by children due to take the 11-plus at the end of the calendar year. ‘Most contained phrases like, “Lord, help me to work quicker and work harder until December comes.”’