AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (2 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

My journey started with a walk that had my heart pounding and my legs burning. Sweat drenched my shirt and got in my eyes. Thirty minutes and I hadn't gone anywhere. That was a year ago on a treadmill after being turned down for a leave of absence to hike the Appalachian Trail. I was determined to hike in a year, even if it meant going AWOL.

For over a year of training on a treadmill, I never got blisters, never went uphill so steeply I could touch the ground ahead of me, and never got rained on. All of these things beset me within days of starting my hike.

Computer programming was the job from which I walked away. My last assignment put me in the dark corner of a little-used building. On a good day, two or three people would pass by my desk. Other programmers seemed content to plug themselves into their machines--attached to the keyboard by their fingers--for nine hours a day. When a programmer had an issue, he would get on the phone to another programmer two cubes away. I could hear both ends of the conversation. They could have heard each other without the phone. I felt out of place. I struggled to stay awake, propped my eyes open with cups of coffee, and fantasized about winning the lottery.

If I had been given a leave of absence the first time I asked, it might have tempered my enthusiasm. Getting turned down solidified my resolve. I pondered the future. Would I continue reporting to a cube until retirement, with a few vacation days sprinkled in? After putting in ten years with my current employer, I would start earning three weeks of vacation a year. Yippee!

This is how it's "done" in middle-class America. Shouldn't I be thankful that life is as comfortable as it is? Most people are devastated if they lose their jobs. At the beginning of April in 2003, I broke the news to my boss. He said, "If you need to have a midlife crisis, couldn't you just buy a Corvette?" I appreciated him for putting me at ease with his humor. I even considered taking "Corvette" for a trail name. He was supportive and did all he could to get me a leave. It just wasn't part of corporate policy.

As I tell my story, I will speak of other inspirations for my hike. In doing so I am not contradicting myself. My job dissatisfaction was just one factor in my decision to hike the AT. Most thru-hikers, when asked, will offer up a single motivation. In part it is the reason currently dominating his thoughts, in part it is the type of answer that is expected, and in part it is the type of answer that is easiest to give. It is not that simple. The reasons for a thru-hike are less tangible than many other big decisions in life. And the reasons evolve. Toward the end, possibly the most sustaining rationale to finish a thru-hike is the fact that you have started one.

I chose to start late--April 25--to avoid the winter, although many nights during my first month on the trail were chilly for my native Floridian blood, dipping into the thirties. I planned to finish quickly, also to avoid cold weather, and to minimize time away from my family (my wife, Juli, and our three daughters). A "quick" thru-hike is four months or less. The typical AT thru-hike takes over five months.

My family drives with me to the start of the trail at Amicalola Falls, and we stay in the wonderful rustic resort located there. I leave my wife and kids in the room and head up the infamously rigorous eight-mile approach trail in a misty morning rain. To my surprise, the hike is not challenging. I feel fresh, and the exertion is overwhelmed by my excitement. New growth on the forest floor, coupled with the dampness, gives the trail a tropical feel. I use the timer on my camera to get a photo of myself walking out into the fog on the trail as it slices through a field of one-foot-tall umbrella-shaped plants.

Resisting the urge to burst down the trail, I focus on self-pservation. I've heard a thru-hike will take five million steps, and I naively reason that I can land softly on every one and keep making painless steps all the way to Katahdin.

On top of Springer Mountain I pick out a small rock, intending to deliver it to Mount Katahdin in Maine. There is a log book, with forty-five thru-hikers signed in on March 1, but today I make the first entry. I've walked the approach trail without seeing anyone.

I pass my first white blaze.

2

On the way down from Springer, I feel a twitch on the outside of my right knee. I lift my foot and shake it, trying to loosen the feeling of contracted thigh muscles. The feeling is still there, faint and foreboding. Nine-tenths of a mile down from the top of Springer, my family waits for me at Big Stamp Gap. I return with them for another night in the lodge. Tomorrow they will return me to the gap, where we will say our goodbyes, and I'll start my hike in earnest.

Back at the lodge, we walk tourist trails near the top of Amicalola Falls. My knee has stiffened, and on every downward step I feel an unmistakable, undeniable twinge of pain. Worry and guilt cast a shadow over the last night with my family. This knee problem could be the end of my hike. I should've done more to prepare myself. I think of all the people that I've told about my adventure. I quit my job. I promised to write updates for my hometown newspaper. I feel foolish. I'll be one of the statistics, one of the hikers that other hikers half-mock for quitting before getting out of Georgia. Juli agrees to delay her trip home until I've passed my first bailout point.

Juli and the girls return me to Big Stamp Gap. My girls are beautiful. Every night I go to their rooms to look at them sleeping. I walk away from them now with plans for them to visit me only once on the trail. It will be the longest I've been separated from them, and it is incredibly difficult. I feel a knot forming in my throat, and tears drop on the trail. I hope no other hiker sees me.

The trail is picturesque, moderate, and varied. There are pines, rhododendrons, stream crossings, and just a few rocky areas. It is all a novelty to me. I try to put into words all that I see. I take pictures of everything. I stop to photograph mica glittering at my feet, unusually formed trees, and the trail submerged by a diverted stream. I pass the day quickly, my senses overloaded with the sights, smells, and sounds of the trail, my head swimming with emotion.

Peter, the first thru-hiker I meet, sits on the side of the trail. He's young, thin, pale, and quiet. I guess he is just out of college, probably from a northern state. We talk little. We are both tentative about socializing, and besides, I feel certain I will meet up with him again soon enough.

I come upon the short side trail to Gooch Gap Shelter sooner than I expect. I've caught up with section hikers looking at Wingfoot, the same guidebook that I have, also questioning if the structure one hundred yards away is really what we think it is.

3

I can see the shelter looks full. Gear is hung from the roof, and I can hear the indistinct hum of conversation. I'm not ready to walk into a shelter full of hikers. I want more time alone to get comfortable with my new world.

Further on, I check out another rickety shelter. This must be the old Gooch Gap Shelter that is to be disassembled. Sleeping bags cover the floor, but there are no hikers in hem; they must be getting water. Happy to have missed them, I hike on. At Gooch Gap there is a gravel road crossing and a camping area full of noisy Boy Scouts and their irritated leaders. My day is getting long--much longer than expected--and now the trail is headed uphill. I was supposed to be coddling my knee. Is that an ache I feel?

On the shoulder of Ramrock Mountain, I finally find an inviting campsite. I am efficient at getting my tarp up and dinner made. Using Wingfoot, I figure I've walked 17.6 miles my first full day on the trail, with a late (10:30) start and a worrisome knee. I'm not ready to berate myself for the long day. It just happened. Walking longer than intended would become routine for me on the AT. If there was a full shelter, an imperfect campsite, or an undesirable crowd, my solution was always to keep walking. The lack of knee pain is inexplicable good fortune. But I'm still not out of the woods, figuratively and literally.

I am on my way--really doing it--hiking the Appalachian Trail. My equipment all has the fresh, crisp, clean look and the new vinyl smell it had in the sporting goods store. I am still clean, shaven, and relatively unworn. The air is crisp and clear, branches are barren, and the forest is budding with the newness of spring. All is in harmony.

Near midnight I wake to relieve myself. I stumble out to a perfectly clear night. There are more stars than sky, beaming through the leafless branches. I am thrilled to be in this place, my adventure under way.

I walk in a T-shirt and shorts. The mountaintops are brown with leafless trees, but the valleys are green, and green is spreading uphill. Wildflowers decorate the trail. Just beyond a road crossing, I see a khaki-clad couple fingering plants at the side of the trail: just what I was looking for. "Do you know these wildflowers?"

First night on the trail.

"A little." They're up for the challenge.

"What is this?" I say, pointing to a plant draped with rust-colored flowers.

"Columbine," they answer in unison.

"Back a ways I saw a waxy yellow flower with five petals."

"Buttercup." They're good at this.

I point to a violet flower at my feet and state, "These are everywhere," implying another question.

"Those are violets," they say with a bit of condescension.

"What is that umbrella-shaped..."

"Mayapple," they answer before I've asked.

Now I'm trying to trip them up. "There is a light blue flower with yellow on the tips of three petals."

"Crested dwarf iris" is the answer, with a tone that taunts. "Is that all you got?"

I tried learning my wildflowers from books. The pictures are sterile and out of context. What I see on the trail is a small percentage of all that exists. Now that I see hey, learning is easy and permanent.

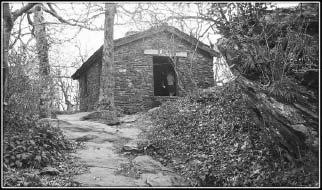

On the way up Blood Mountain, there are many people strolling along without packs. A parking lot is thirty minutes away. Teens in Skechers and jeans give me curious looks. I'm sure when I get out of earshot they ask each other, "Why is that dumbass carrying a backpack?" An old Civilian Conservation Corps stone building on the summit still serves as a shelter. Many people are scattered around the rocky summit, none of them encumbered by a backpack. The smell of marijuana and sounds of a foreign language emanate from the shelter. The building is occupied by a handful of young Europeans in goth attire with more piercings than I can count.