B0041VYHGW EBOK (137 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Such ways of looking at genre are usually called

reflectionist,

because they assume that genres reflect social attitudes, as if in a mirror. But some critics would object that reflectionist readings can become oversimplified. If we look closely at a genre film, we usually discover complexities that nuance a reflectionist account. For instance, if we look beyond Ripley, the protagonist of

Aliens,

we find that all the characters lie along a continuum running between “masculine” and “feminine” values, and the survivors of the adventure, male or female, seem to blend the best of both gender identities. Moreover, often what seems to be social reflection is simply the film industry’s effort to exploit the day’s headlines. A genre film may reflect not the audience’s hopes and fears but the filmmakers’ guess about what will sell.

Whether we study a genre’s history, its cultural functions, or its representations of social trends, conventions remain our best point of departure. As examples, we look briefly at three significant genres of American fictional filmmaking.

The Western

The Western emerged early in the history of cinema, becoming well established by the early 1910s. It is partly based on historical reality, since in the American West there were cowboys, outlaws, settlers, and tribes of Native Americans. Films also based their portrayal of the frontier on songs, popular fiction, and Wild West shows. Early actors sometimes mirrored this blend of realism and myth: cowboy star Tom Mix had been a Texas Ranger, a Wild West performer, and a champion rodeo rider.

Quite early, the central theme of the genre became the conflict between civilized order and the lawless frontier. From the East and the city come the settlers who want to raise families, the schoolteachers who aim to spread learning, and the bankers and government officials. In the vast natural spaces, by contrast, thrive those outside civilization—not only the American Indians but also outlaws, trappers and traders, and greedy cattle barons.

Iconography reinforces this basic duality. The covered wagon and the railroad are set against the horse and canoe; the schoolhouse and church contrast with the lonely campfire in the hills. As in most genres, costume is iconographically significant, too. The settlers’ starched dresses and Sunday suits stand out against Indians’ tribal garb and the cowboys’ jeans and Stetsons.

Interestingly, the typical Western hero stands between the two thematic poles. At home in the wilderness but naturally inclined toward justice and kindness, the cowboy is often poised between savagery and civilization. William S. Hart, one of the most popular early Western stars, crystallized the character of the “good bad man” as a common protagonist. In

Hell’s Hinges

(1916), a minister’s sister tries to reform him; one shot represents the pull between two ways of life

(

9.9

).

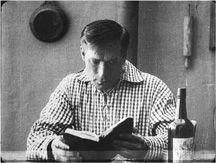

9.9 The “good bad” hero of

Hell’s Hinges

reads the Bible, a bottle of whiskey at his elbow.

The in-between position of the hero affects common Western plots. He may start out on the side of the lawless, or he may simply stand apart from the conflict. In either case, he becomes uneasily attracted to the life offered by the newcomers to the frontier. Eventually, the hero decides to join the forces of order, helping them fight hired gunmen, bandits, or whatever the film presents as a threat to stability and progress.

As the genre developed, it adhered to a social ideology implicit in its conventions. White populations’ progress westward was considered a historic mission, while the conquered indigenous cultures were usually treated as primitive and savage. Western films are full of racist stereotypes of Native Americans and Hispanics. Yet on a few occasions, filmmakers treated Native American characters as tragic figures, ennobled by their closeness to nature but facing the extinction of their way of life. The best early example is probably

The Last of the Mohicans

(1920).

Moreover, the genre was not wholly optimistic about taming the wilderness. The hero’s eventual commitment to civilization’s values was often tinged with regret for his loss of freedom. In John Ford’s

Straight Shooting

(1917), Cheyenne Harry (played by Harry Carey) is hired by a villainous rancher to evict a farmer, but he falls in love with the farmer’s daughter and vows to reform. Rallying the farmers, Harry helps defeat the rancher. Still, he is reluctant to settle down with Molly

(

9.10

).

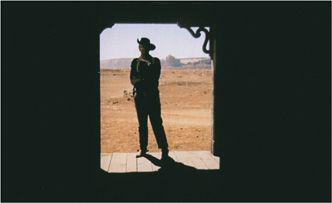

9.10 In

Straight Shooting,

the hero stands framed in the farmhouse doorway, halfway between the lure of civilization and the call of the wilderness.

Within this set of values, a great many conventional scenes became standardized—the Indians’ attack on forts or wagon trains, the shy courting of a woman by the rough-hewn hero, the hero’s discovery of a burned settler’s shack, the outlaws’ robbery of a bank or stagecoach, the climactic gunfight on dusty town streets. Writers and directors could distinguish their films by novel handlings of these elements. In Sergio Leone’s flamboyant Italian Westerns, every convention is stretched out in minute detail or amplified to a huge scale, as when the climactic shootout in

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

(1966) is filmed to resemble a bullfight

(

9.11

).

9.11 A low wall creates an arena in which the three-way shoot-out occurs at the end of

For a Few Dollars More.

There were narrative and thematic innovations as well. After such liberal Westerns of the 1950s as

Broken Arrow

(1950), native cultures began to be treated with more respect. In

Little Big Man

(1970) and

Soldier Blue

(1970), the conventional thematic values were reversed, depicting Indian life as civilized and white society as marauding. Some films played up the hero’s uncivilized side, showing him perilously out of control (

Winchester 73,

1950), or even psychopathic (

The Left-Handed Gun,

1958). The heroes of

The Wild Bunch

(1969) would have been considered unvarnished villains in early Westerns.

“I knew Wyatt Earp. In the very early silent days, a couple of times a year he would come up to visit pals, cowboys he knew in Tombstone; a lot of them were in my company. I think I was an assistant prop boy then and I used to give him a chair and a cup of coffee, and he told me about the fight at the O.K. Corral. So in

My Darling Clementine,

we did it exactly the way it had been. They didn’t just walk up the street and start banging away at each other; it was a clever military manoeuvre.”— John Ford, director,

Stagecoach

The new complexity of the protagonist is evident in John Ford’s

The Searchers

(1956). After a Comanche raid on his brother’s homestead, Ethan Edwards sets out to find his kidnapped niece Debbie. He is driven primarily by family loyalty but also by his secret love for his brother’s wife, who has been raped and killed by the raiders. Ethan’s sidekick, a young man who is part Cherokee, realizes that Ethan plans not to rescue Debbie but to kill her for becoming a Comanche wife. Ethan’s fierce racism and raging vengeance culminate in a raid on the Comanche village. At the film’s close, Ethan returns to civilization but pauses on the cabin’s threshold

(

9.12

)

before turning back to the desert.

9.12 The closing shot of

The Searchers.

The shot eerily recalls Ford’s

Straight Shooting

(

9.10

); John Wayne even repeats Harry Carey’s characteristic gripping of his forearm

(

9.13

).

Now, however, it seems that the drifting cowboy is condemned to live outside civilization because he cannot tame his grief and hatred. More savage than citizen, he seems condemned, as he says of the souls of dead Comanches, “to wander forever between the winds.” This bitter treatment of a perennial theme illustrates how drastically a genre’s conventions can change across history.

9.13 Harry Carey’s gesture in

Straight Shooting.

While the Western is most clearly defined by subject, theme, and iconography, the horror genre is most recognizable by the emotional effect it tries to arouse. The horror film aims to shock, disgust, repel—in short, to horrify. This impulse is what shapes the genre’s other conventions.

What can horrify us? Typically, a monster. In the horror film, the monster is a dangerous breach of nature, a violation of our normal sense of what is possible. The monster might be unnaturally large, as King Kong is. The monster might violate the boundary between the dead and the living, as vampires and zombies do. The monster might be an ordinary human who is transformed, as when Dr. Jekyll drinks his potion and becomes the evil Mr. Hyde. Or the monster might be something wholly unknown to science, as with the creature in the

Alien

films. The genre’s horrifying emotional effect, then, is usually created by a character convention: a threatening, unnatural monster.