B0041VYHGW EBOK (8 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

A feature-length film is a very long ribbon of images, about two miles for a two-hour movie. In most theaters, the projector carries the film at the rate of 90 feet per minute. In the typical theater, the film is mounted on one big platter, with another platter underneath to take it up after it has passed through the projector

(

1.14

).

In digital theatrical projection, the film is stored on discs.

1.14 Most multiscreen theaters use platter projection, which winds the film in long strips and feeds it to a projector (seen in the left rear). The film on the platters is an Imax 70mm print.

The film strip that emerges from the camera is usually a

negative.

That is, its colors and light values are the opposite of those in the original scene. For the images to be projected, a

positive

print must be made. This is done on another machine, the

printer,

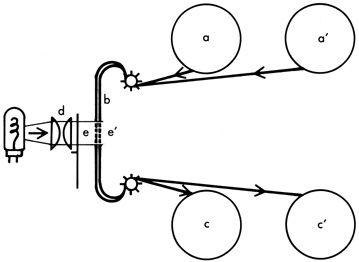

which duplicates or modifies the footage from the camera. Like a projector, the printer controls the passage of light through film—in this case, a negative. Like a camera, it focuses light to form an image—in this case, on the unexposed roll of film. All printers are light-tight chambers that drive a negative or positive roll of film from a reel (a) past an aperture (b) to a take-up reel (c). At the same time, a roll of unexposed film (a′, c′) moves through the aperture (b), either intermittently or continuously. By means of a lens (d), light beamed through the aperture prints the image (e) on the unexposed film (e′). The two rolls of film may pass through the aperture simultaneously. A printer of this sort is called a

contact

printer

(

1.15

).

Contact printers are used for making work prints and release prints, as well as for various special effects.

1.15 The contact printer.

Although the filmmaker can create nonphotographic images on the filmstrip by drawing, painting, or scratching, most filmmakers have relied on the camera, the printer, and other photographic technology.

If you were to handle the film that runs through these machines, you’d notice several things. One side is much shinier than the other. Motion picture film consists of a transparent acetate

base

(the shiny side), which supports an

emulsion,

layers of gelatin containing light-sensitive materials. On a black-and-white filmstrip, the emulsion contains grains of silver halide. When light reflecting from a scene strikes them, it triggers a chemical reaction that makes the crystals cluster into tiny specks. Billions of these specks are formed on each frame of exposed film. Taken together, these specks form a latent image that corresponds to the areas of light and dark in the scene filmed. Chemical processing makes the latent image visible as a configuration of black grains on a white ground. The resulting strip of images is the negative, from which positive prints can be struck.

Color film emulsion has more layers. Three of these contain chemical dyes, each one sensitive to a primary color (red, yellow, or blue). Extra layers filter out the light from other colors. During exposure and development, the silver halide crystals create an image by reacting with the dyes and other organic chemicals in the emulsion layers. With color negative film, the developing process yields an image that is opposite, or complementary, to the original color values: for example, blue shows up on the negative as yellow.

What enables film to run through a camera, a printer, and a projector? The strip is perforated along both edges, so that small teeth (called

sprockets

) in the machines can seize the perforations (sprocket holes) and pull the film at a uniform rate and smoothness. The strip also reserves space for a sound track.

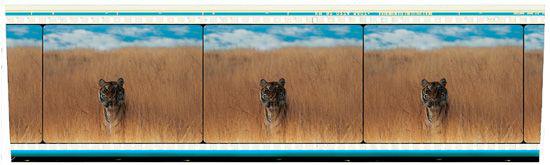

The size and placement of the perforations and the area occupied by the sound track have been standardized around the world. So, too, has the width of the film strip, which is called the

gauge

and is measured in millimeters. Commercial theaters use 35mm film, but other gauges also have been standardized internationally: Super 8mm, 16mm, and 70mm

(

1.16

–

1.20

).

1.16 Super 8mm has been a popular gauge for amateurs and experimental filmmakers.

Year of the Horse,

a concertfilm featuring Neil Young, was shot partly on Super 8.

1.17 16mm film is used for both amateur and professional film work. A variable-area optical sound track (

p. 11

) runs down the right side.

1.18 35mm is the standard theatrical film gauge. The sound track, a variable-area one (

p. 11

), runs down the left alongside the images.

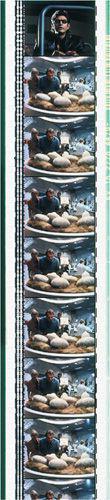

1.19 In this 35mm strip from

Jurassic Park,

note the optical stereophonic sound track (

p. 11

), encoded as two parallel squiggles. The stripe along the left edge, the Morse code–like dots between the stereophonic track and the picture area, and the speckled areas around the sprocket holds indicate that the print can also be run on various digital sound systems.

1.20 70mm film, another theatrical gauge, was used for historical spectacles and epic action films into the 1990s. In this strip from

The Hunt for Red October,

a stereophonic magnetic sound track runs along both edges of the filmstrip.

Usually image quality increases with the width of the film because the greater picture area gives the images better definition and detail. All other things being equal, 35mm provides significantly better picture quality than does 16mm, and 70mm is superior to both. The finest image quality currently available for public screenings is that offered by the Imax system

(

1.21

).

1.21 The Imax image is printed on 70mm film but runs horizontally along the strip, allowing each image to be 10 times larger than 35mm and triple the size of 70mm. The Imax film can be projected on a very large screen with no loss of detail.