B007M836FY EBOK (31 page)

Authors: Kate Summerscale

In the late 1860s, Henry moved back to Edinburgh with his new wife, and took over a yard in Glasgow on the River Clyde, which was replacing the Thames as the centre of iron shipbuilding. In 1869 he patented a design to improve the operation of dredgers, boats that used a revolving ladder of buckets to heave mud and silt off the riverbed.

Isabella left Reigate in the late 1860s and moved into a rented house on the village green in Frant, Kent. Henry’s sister Helena was living a few miles away, having moved with her family from Brighton to Tunbridge Wells. Despite all the disclosures of the diary and the court, Helena and her children seemed to think more highly of Isabella than of Henry. In April, one of Helena’s daughters wrote in the family journal that she had received a letter from Isabella: ‘a splendid letter writer!’ she reported, ‘and whatever her faults may be [she] is a good mother to her sons. I cannot but feel much interested for her.’ Helena invited Isabella to call on them. On 4 April, Helena’s son Ernest wrote in the family journal: ‘Mrs Robinson (Stanley’s Mother) came at Mother’s invitation to see us on Saturday and stayed to tea, having walked in from Frant a distance of about three and a half miles. I went down to the Station with her in the evening.’ On a return visit to her house in Frant, Ernest met Alfred, who had now qualified as a marine engineer.

In 1874, Alfred, at thirty-three, married the eighteen-year-old Rosine Cooper, the daughter of a silversmith. Two years after that he went into partnership with his younger half-brother Otway who, after dabbling in the cotton business in the 1860s, had joined the Merchant Navy. Otway and Alfred

bought and sailed iron cargo ships: they purchased the

Trocadero

, the

Frascati

, the

Alcazar

and the

Valentino

in South Shields in the 1870s, and the

Harley

in Glasgow in the 1880s. Otway sometimes acted as master of the vessels, and Alfred as first engineer.

Henry moved back down to England, and by 1876 was living in Norwood, Surrey. ‘He has become quite an old broken down man,’ reported a niece. ‘He has almost lost his memory.’ Henry’s business, too, was faltering – ‘the firm is not making a penny just now’ – and in 1877, Tom Waters broke with his uncle: ‘He could not stand his idiotic interferences any longer.’ The second Mrs Robinson, to whom Henry’s sister Helena referred as ‘poor little “Marie”,’ bore her husband three sons.

Isabella, restless as ever and perhaps pursued by her reputation, moved from Frant to St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex, and then to a house called Fairlight in Bromley, Kent.

Each of the famous fictional adulteresses of the nineteenth century – Flaubert’s Emma Bovary, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and Zola’s Thérèse Raquin – died at her own hand, her sins having engulfed her in grief and shame. Isabella too was killed by her own hand, though in less sensational circumstances. At her house in Bromley on 20 September 1887 she discovered an infected abscess on one of her thumbs. Three days later she died of septicemia, with Otway at her side. On the death certificate, he gave her age as seventy, and her marital status as widow. That December, Henry died in Dublin aged eighty.

Isabella left everything to Otway – she had made her will in 1864, soon after he alienated himself from his father by running away to join her. Otway did not marry. When he died in the seaside town of Whitstable, Kent, in 1930, aged eighty-five, he bequeathed his land and cottages and furniture (worth about £6,000) to a friend and neighbour called Alfred Harvey. He stated in his will that he wished to leave the remainder of his estate – about £7,000 – to the German conscripts wounded

in the First World War; and, if that proved impossible, to those soldiers injured by British forces in the Boer War. He told Harvey that he was ‘fed up with England’, a phrase that

Time

magazine used as a headline when it ran a short article about Captain Robinson’s unusual bequest. Otway’s sympathies lay with the soldiers of countries defeated by the British Empire: men who, like him, had been dragged into wars of others’ making and left hurt and humiliated by fights that they had not started.

The original diaries and the copies made of them were, as far as we know, destroyed.

Coda

Do you also pause to pity?

In a court of law, the value of Isabella’s diary was dubious. Like any book of its kind, it was a work of anticipation as much as memory – it was provisional and unsteady, existing at the edge of thought and act, wish and deed. But as a piece of raw emotional testimony, it was a startling work, an awakening or an alarm. The diary gave its Victorian readers a flash of the future, as it gives us a flicker of our own world taking shape in the past. It may not tell us, for certain, what happened in Isabella’s life, but it tells us what she wanted.

Isabella’s journal offered a glimpse of the freedoms to which women might aspire if they gave up their belief in God and in marriage – rights to possessions and money, to the custody of children, to sexual and intellectual adventure. It also hinted at the pain and confusion that such freedoms would entail. In the decade in which the Church relinquished its control over marriage and Darwin threw into deeper doubt the spiritual origins of mankind, her journal was a sign of the tumult to come.

In an undated diary entry, Isabella explicitly addressed a future reader. ‘One week of a new year already gone,’ she began. ‘Ah! If

I

had the hope of another life of which my mother speaks (she and my brother wrote kindly this day),

and which Mr B urged us to secure, all would be bright and well with me. But, alas! I have it not, nor can possibly obtain

that

; and as to this life, anger, sensuality, helplessness, hopelessness, overpower and rend my soul, and fill me with remorse and foreboding.’

‘Reader,’ she wrote, ‘you see my inmost soul. You must despise and hate me. Do you also pause to pity? No; for when you read these pages all will be over with one who was “too flexible for virtue; too virtuous to make a proud, successful villain”.’ Isabella was quoting loosely from Hannah More’s play

The Fatal Falsehood

(1779), in which a young Italian count – a ‘compound of strange, contradicting parts’ – falls desperately in love with a woman promised to his best friend.

When Edward Lane first read the diary, this entry in particular drew his anger and scorn: ‘The address to the Reader!’ he wrote to Combe. ‘

Who is

the Reader? Was this precious journal, then, intended for publication, or if not quite so bad as that, was it meant for an heirloom for her family? On either supposition, I say there is clear madness here – and if there were not another passage in the whole farrago to warrant that view, to my mind this one alone wd be sufficient.’

Yet Isabella’s address to an imagined reader might, on the contrary, point to the clearest explanation of all for why she kept her diary. Part of her, at least, wanted to be heard. She harboured a hope that somebody considering her words after her death would hesitate before damning her; that her story might one day be met with compassion, even love. In the absence of a spiritual afterlife, we were the only future she had.

‘Good night,’ she ended, with a desolate blessing: ‘May you be more happy!’

My thanks to the staff of the British Library, the London Library, the National Archives and the Wellcome Library in London; to the staff of the local record offices in Hereford, Reading, Shrewsbury and Whitehaven; to Pauline Dunne at the National Archives in Dublin and to Alison Metcalfe at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh. For permission to quote from their archives, thanks to the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland, to the Cumbria Archive & Local Studies Centre (Whitehaven) and to the Tairawhiti Museum in Gisborne, New Zealand. Many thanks to Meg Vivers for sharing her excellent research into the Robinson family; to Mark Robinson for his information about his great-great-grandfather; and to Phyllis Ray and Ruth Walker for passing on their knowledge of the Walkers. For arranging for me to look round some of the houses in which Isabella Robinson and her friends lived, I am grateful to Clynt Wellington in Surrey; to Ann and Freddy Johnston in Ludlow; and to Florence Shanks and Lucinda Miller in Edinburgh.

Thanks to all the friends and family who have helped me with this book, among them Lorna Bradbury, Alex Clark, Toby Clements, Will Cohu, Tamsin Currey, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, Claudia FitzHerbert, Miranda Fricker, Stephen Grosz, Victoria Lane, Ruth Metzstein, Sinclair McKay, Daniel Nogués, Marina Nogués, Tasio Nogués, Stephen O’Connell, Kathy O’Shaughnessy, Robert Randall, John Ridding, Wycliffe Stutchbury, Ben Summerscale, Juliet Summerscale, the late Peter Summerscale, Lydia Syson, Frances Wilson, Keith

Wilson, the mothers who meet at the Coffee Cup in Hampstead and the writers who meet at the Novel History Salon in Bloomsbury. Thank you especially to my son, Sam.

A big thank you to my agent, David Miller, as ever; to his colleagues at Rogers, Coleridge & White, including Stephen Edwards, Alex Goodwin and Laurence Laluyaux; and to Julia Kreitman of The Agency in London and Melanie Jackson in New York. My thanks to Richard Rose for his excellent suggestions and advice. Thank you to everyone at Bloomsbury in London for making the publication process such a pleasure, among them Geraldine Beare, Richard Charkin, Jude Drake, Sarah-Jane Forder, Alexa von Hirschberg, Nick Humphrey, Kate Johnson, David Mann, Paul Nash, Anya Rosenberg, Alice Shortland, Anna Simpson and – particularly – my editor, Alexandra Pringle, whose guidance has been invaluable. Many thanks also to the other publishers who have supported this project: George Gibson and the rest of Bloomsbury in New York, Ann-Catherine Geuder in Berlin, Dominique Bourgois in Paris, Ludmila Kuznetsova in Moscow, Andrea Canobbio in Turin, Sofia Ribeiro in Lisbon and Henk ter Borg in Amsterdam.

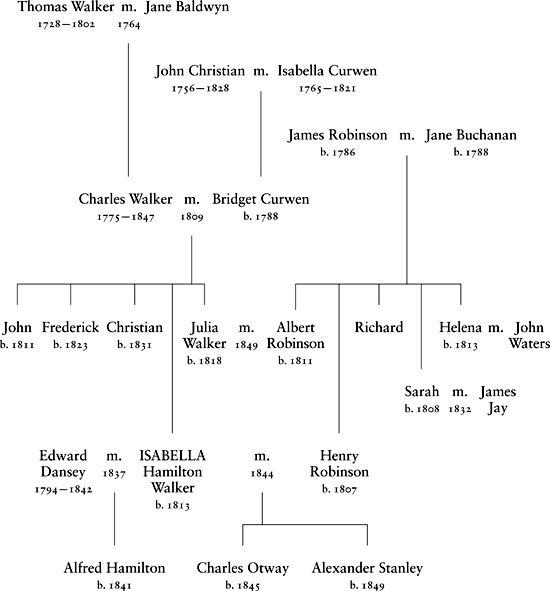

THE ROBINSONS

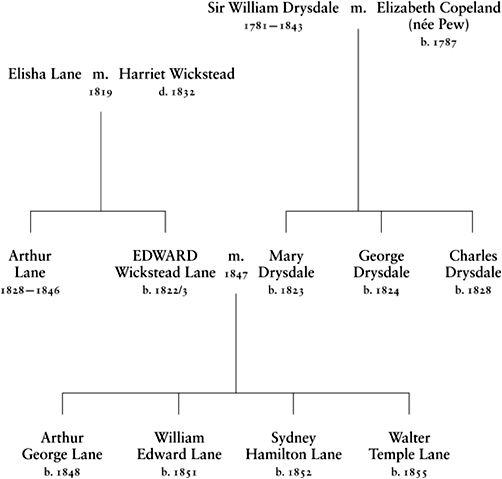

THE LANES

List of lawyers in the

Robinson Divorce Trial

THE JUDGES

Sir Alexander Cockburn, Bt, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas Sir Cresswell Cresswell, Judge Ordinary of the Court of Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Sir William Wightman

THE BARRISTERS

For Henry Robinson Montagu Chambers QC

Jesse Addams QC, DCL

John Karslake

For Isabella Robinson Robert Phillimore QC, DCL

John Duke Coleridge

For Edward Lane

William Forsyth QC

William Bovill QC

James Deane QC, DCL

UNPUBLISHED SOURCES:

Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes file J77/44/R4, containing papers on the Robinson divorce, NA

Court of Chancery file C15/550/R24,

Robinson v Robinson

, NA

George Combe’s journals for 1856, 1857 and 1858 (MS 7431), NLS

Journal of Robert Chambers (Deps 341/30 and 341/33) and authors’ ledger (Dep 341/289), NLS

Journals and letters of Henry Robinson’s sister Helena Waters and her family, WG Papers

Letters from Mary Drysdale to Jane Williams, in the Clyde Company Papers at the State Library of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

Letters of Charles and Bridget Walker and Henry Curwen in Curwen family archives (refs DCu/3/31, DCu/3/81 and 3/7), Cumbria Record Office and Library, Whitehaven, Cumbria

Letters of William Copland and Mary Drysdale to John Murray, John Murray archive, NLS

Letters to and copybook of George Combe between 1850 and 1858: letters by GC from 1850 to April 1854 are in MS 7392; from April 1854 to June 1858 in MS 7393. Letters to GC cited in this book are in MS 7350, MS 7365 and MSS 7369–7374, Combe Collection, NLS