B008AITH44 EBOK (44 page)

Authors: Brigitte Hamann

CHAPTER EIGHT

RIDES TO HOUNDS

I

n 1873, the year of the World Exhibition, Elisabeth met more social obligations than in any year before or after—though more under duress than of her own free will, and with many of her familiar caprices. Now she was in need of rest—far from Vienna, of course. Elisabeth wrote to her mother from Gödöllö, “here one lives so quietly without relatives and vexations, and there [in Vienna] the whole imperial family! Here, too, I am at ease as in the country, can walk alone, go for drives alone”—but especially go horseback riding.

1

The Puszta sands seemed made for the hours of daily rides. There were still wild horses in the region. The landscape was romantic and rugged, just what Elisabeth loved. She also took part in the most difficult hunts. The wife of the Belgian envoy, Countess de Jonghe, wrote, “It is supposedly

wonderful to see her at the head of all the riders and always in the most dangerous spots. The enthusiasm of the Magyars knows no bounds, they break their necks to follow more closely. Young Elemer Batthyány almost lost his life, fortunately only his horse died. Near their beautiful queen, the Hungarians become royalist to a degree that, it is said, if these hunts had begun before the elections, the government could have incurred great savings.”

2

Gödöllö was Elisabeth’s empire. Here her laws prevailed, and they had little to do with questions of rank and protocol. Visitors were selected, not according to their standing among the nobility, but by their riding skills. Elisabeth collected around herself the elite of the Austro-Hungarian

horsemen

—young, rich aristocrats who spent their lives almost exclusively at race courses and on hunting and had no obligations or work of any kind.

For years, her favorite was Count Nikolaus Esterházy, the famous “Sports Niki.” His huge estate adjoined Gödöllö. He was famous for the thoroughbreds he raised, and he supplied Elisabeth’s stables with horses. During the 1860s and 1870s, Niki Esterházy was the ranking horseman of Austria-Hungary, for many years the undisputed master of the hunt, one of the founders of the Jockey Club in Vienna—besides being a dashing, good-looking bachelor and social lion, two years younger than the Empress.

“The handsome prince” Rudolf Liechtenstein, could also be found at Elisabeth’s side. He was (and remained all his life) a bachelor, a little younger than the Empress, a well-known horseman and ladies’ man.

During

the 1870s, he also distinguished himself as a composer of art songs. He was devoted to the Empress in perpetual adoration.

Count Elemer Batthyány’s frequent presence at Gödöllö caused a

particular

sensation. For he was a son of the Hungarian prime minister whom the young Emperor Franz Joseph had executed in 1849 under humiliating circumstances. Batthyány’s widow as well as Elemer refused to meet the Emperor; they went so far as to snub him openly by refusing to greet him when they met by accident.

Elisabeth never left the slightest doubt that she condemned most harshly the methods of Austrian policy and justice during the Revolution of 1848. She brought considerable understanding to young Batthyány’s intransigent stance and obliged him in any way she could.

Of course, she invited Elemer to Gödöllö even when the Emperor was in residence—and, of course, Batthyány turned away whenever Franz Joseph came near him. And no matter how rigidly Franz Joseph insisted on court etiquette—here in his wife’s company, he allowed Batthyány to

snub him without protesting; he made desperate efforts to ignore awkward situations, and in this way he, too, showed some understanding.

Of course, Gyula Andrássy was also a frequent visitor at Gödöllö. He was still an outstanding horseman. But he could not easily keep up with the competition offered by Esterházy, Liechtenstein, and Batthyány; after all, he was the imperial and royal foreign minister, had his hands full with work, and could not spend his days on fancy riding tricks. Furthermore, by now he was past fifty. His interest in racing had waned.

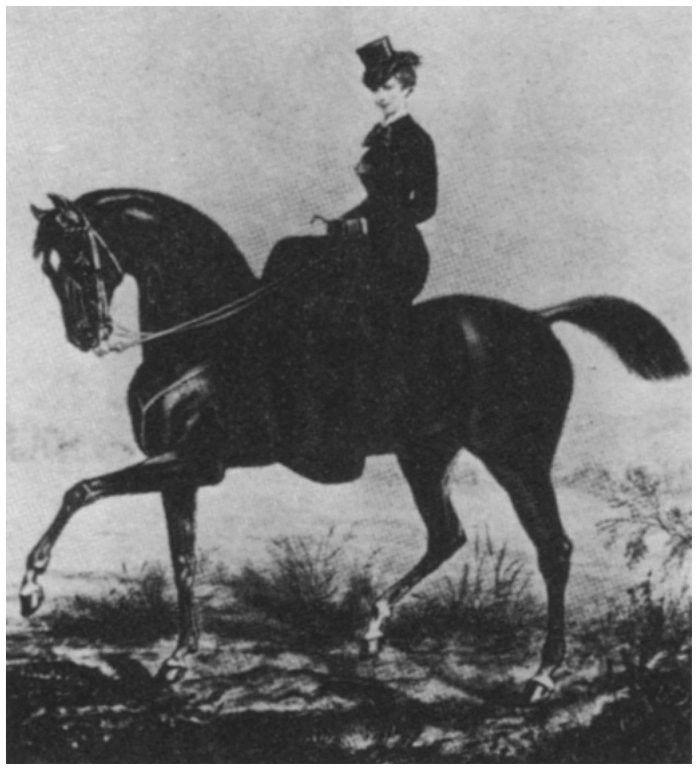

Sisi also invited her niece Baroness Marie Wallersee to Gödöllö. The daughter of her brother Ludwig and the actress Henriette Mendel of Munich, Marie was not only a strikingly pretty girl (a fact which, as was well known, Sisi valued highly), but also an outstanding horsewoman. Elisabeth enjoyed provoking the nobility with the girl’s presence. For in spite of her close kinship with the Empress, “little Wallersee” was not socially acceptable, because her mother was a bourgeoise and she was a “bastard.” Elisabeth turned Marie into her creature, fitting her out in the latest fashions, teaching her the necessary social polish and the required haughtiness toward men. She clearly relished the sensation the beautiful young woman at her side created. Marie: “Three times a week there was a hunt. Oh, it was marvelous! On horseback, Elisabeth looked enchanting. Her hair lay in heavy braids around her head, over it she wore a top hat. Her dress fitted like a glove; she wore high laced boots with tiny spurs and she pulled three pairs of gloves over each other; the unavoidable fan was always stuck in the saddle.” (The Empress used the fan swiftly whenever curious onlookers appeared, to hide her face.)

Elisabeth also made the young girl the confidante of her secrets. Marie Wallersee: “I thoroughly enjoyed the long rides with the Empress, who occasionally found pleasure in disguising herself as a boy. Of course, I had to follow her example; but I still recall the shame that tortured me when I saw myself for the first time in trousers. Elisabeth imagined that this crazy whim was not generally known in Gödöllö; in reality, everyone was talking about it. Only Franz Joseph, I believe, had no idea of what was everyone’s secret.”

Other habits Elisabeth cultivated in Gödöllö also soon became matters of general knowledge, at least at the Viennese court. For example, the Empress had an arena built like the one her father had had in Munich at one time. There she put her mounts through their paces and worked with circus horses. Marie: “It was a charming sight when Aunt in her black velvet riding costume led her small Arab horse around the ring in dancing step. True, for an empress, it was a somewhat uncommon occupation.”

3

Even the Bavarian family, inured to odd behavior by Max, was not a little astonished when Valerie proudly told Prince Regent Luitpold, “Uncle Luitpold, Mama on her horse can already jump through two hoops.”

4

Her instructors in these circus tricks were the most famous equestriennes from the Circus Renz, Emilie Loiset and Elise Petzold. Elise especially was a frequent guest at Gödöllö and was considered a personal confidante of the Empress. Elisabeth showed her affection for Elise (who was also known as Elise Renz in court circles) by making a gift to her of one of her favorite horses, Lord Byron, and inviting the circus equestrienne along at the most elegant hunts. When twenty-five-year-old Emilie Loiset had a fatal

accident

in the ring, few newspapers omitted mentioning that she had been close to the Empress of Austria.

The head of the Circus Renz, Ernst Renz, occasionally advised

Elisabeth

when she was buying a horse. He, too, became a celebrity in the more exalted circles because of the Empress’s favors.

At Gödöllö, a former circus director named Gustav Hüttemann gave the Empress lessons in dressage. Emperor Franz Joseph put up with all these activities resignedly, even preserving his sense of humor, telling Herr Hüttemann, “Well, the roles are reversed. Tonight, the Empress takes the stage as the equestrienne. You put the horse through its paces. And I function as your equerry.”

Besides the circus riders, Elisabeth also invited gypsies. Because she loved gypsy music, she ignored all the unpleasantness these visits brought with them, glossing it over generously with laughter. The men servants, including the Emperor’s personal valet, were outraged: “In Gödöllö, all sorts of shady folk roamed about—filthy men, women, and children muffled in rags. Often the Empress brought a whole community to the castle, had them entertained and lavishly provided with food.”

5

All curiosities and abnormalities attracted Elisabeth’s interest. Once she ordered the latest circus attraction to be sent from Budapest to Gödöllö—two black girls joined together. “But the mere thought horrified the Emperor so much that he absolutely refused to look at them,” the Empress wrote to Duchess Ludovika, who was, after all, used to such things on a large scale from her Max.

6

The more intensively and exclusively Elisabeth occupied herself with horseback riding, the more time she spent in the company of horsemen, the more dissatisfied she became with Gödöllö: The hunting season was too short, since it did not begin until after the harvest (in early September) and traditionally ended on November 3, St. Hubert’s Day. The dense forests

were an obstacle to the hunt. Most of all, there were too few fences and too few chances to jump; the countryside offered merely small open ditches instead of the high fences typical of the English hunts. And riding to hounds on the English model was the ne plus ultra even for Austrian gentleman riders. Whoever could not boast of successes or at least

participation

in English hunts—as Niki Esterházy, for example, could—was not taken seriously among the horseback elite.

Ex-Queen Marie of Naples, Sisi’s beautiful sister, had already followed the fashion and (with the help of the House of Rothschild) had bought a hunting lodge in England. Now she gushed to Elisabeth about the English hunts and invited her sister to England in 1874. The official reason for this, the Empress’s first trip to England, was that little Marie Valerie absolutely required ocean bathing, for which the Isle of Wight was

eminently

suited.

In order to forestall any political complications, Elisabeth traveled under the alias of Countess von Hohenembs. Nevertheless, she could not avoid paying a courtesy call on Queen Victoria, who was spending the summer at Osborne, also on the Isle of Wight. Elisabeth’s surprise visit, on very short notice, was not convenient for the Queen. Somewhat annoyed, Victoria wrote to her daughter, “The Empress insisted on seeing me today. All of us are disappointed. I cannot call her a great beauty. She has beautiful skin, a magnificent figure, and pretty little eyes and a not very pretty nose. I must say that she looks much better in

grande

tenue

[dressed in state], when she can be seen with her beautiful hair, which is to her advantage. I think Alix [the Princess of Wales] much prettier than the Empress.”

The Prussian Crown Princess Victoria, the British Queen’s oldest

daughter,

was also on the Isle of Wight, at Sandown. She, too, was disappointed by Elisabeth’s visit and wrote to her mother, “The Empress of Austria also came here yesterday—she would not accept any of the refreshments she was offered. But afterwards we heard that she had gone to the hotel in Sandown and dined there, which we did find fairly strange. She did not look her best, and I believe her beauty has faded a great deal since last year, though she is still pretty! Nor was she dressed very becomingly.” Victoria agreed with her mother that the English Princess Alix was prettier; “but the Empress is more striking than any lady I have ever seen. The beautiful Empress is a very strange person, as far as her daily schedule is concerned. The greatest part of the morning she spends sleeping on the sofa. She dines around 4 and rides all evening quite alone and never less than three hours and gets furious when anything else is planned. She wants to see no one or be seen anywhere.”

7

Sisi, for her part, wrote to her husband about her (only) official visiting day on Wight—“the most fatiguing day of the whole trip,” she noted. “The Queen was very friendly, said nothing unpleasant, but I do not care for her…. I was altogether very polite, and everyone seemed astonished. But now I have done everything. Everyone understands completely that I want quiet, and they do not want to embarrass me.”

8

To Duchess Ludovika she wrote that “such things bore” her. Sisi’s letters in general often mentioned boredom. It was probably also the reason for her dream of faraway places. “What I would most like to do is go to America for a little while, the ocean draws me so much whenever I look at it. Valerie would like to go along, too, for she found the sea voyage charming. All the others with few exceptions were sick.”

9

Instead of paying another call on the Queen, Elisabeth sought out celebrated stud farms to look at English hunting horses, but she made no purchases. Elisabeth to her husband: “I also saw some very beautiful horses, but all of them very expensive. The one I would most have liked to have cost 25,000 fl. so naturally unaffordable.”

10