Back of Beyond (34 page)

The clerk is oblivious of it all. I catch occasional glimpses of him smiling and chatting to his colleagues and then turning back to snarl at his customers. He writes very slowly in a huge ledger. It’s twenty degrees hotter over here, and I’m beginning to hallucinate about quiet hotels, soft easy chairs, air-conditioning, and ultra-dry martinis.

Five minutes of sardine-can serendipity. Then suddenly I’m at the grille. Only the clerk is gone. I can hear him laughing somewhere behind the rickety tables piled high with browned ledgers. As soon as he returns the smile vanishes and a mask of utter disdain slides over his face like a gray film.

“Please, I don’t have much time. Can I have a first class birth reservation for Delhi?”

“It is too late.”

“I can just make it, I think.”

The clerk sneers.

“Where are your forms?”

“What forms?”

“Your reservation forms.”

“Look, can’t I just buy a ticket? Forget the berth.”

“All first class is for berths.”

Stalemate. The big clock over the platform entrance ticks on, aloof as Victoria herself.

“Okay. What do I need?”

“You need reservation forms.”

“Where do I get them?” (I already know the answer.)

“At the last window” (another sneer). “Sir.”

Stumbling over more bodies. More waiting. Finally I am handed a long sheet of stained paper with enough questions to justify a mortgage.

I shall obviously miss the train, but I’m in too deep now to think about anything else.

Back in line again, my form completed. I’m allowed to go to the front of the queue and face the same sneering clerk.

“All berths are booked…sir.”

I’m about to have a fit. I’ll never get out of this place. Then the clerk peers more closely at my form.

“You are British and you live in America?”

“Yes.”

“You are a tourist?”

“Yes—why? Do I need more papers?” (My turn to sneer now.)

“Oh no, no, sir. Not at all. But you should have informed me.”

“Why?”

“There are special seats for tourists.”

“You mean you’re not fully booked?”

“Oh no, sir. You can have a berth. No problem at all.”

“Wonderful!”

“Yes. The office next to your previous place will be dealing with this, sir.”

“You mean—I go somewhere else!”

“Yes, sir. Of course. You are special category.”

“You can’t give me a ticket?”

“No, sir.”

We stare at each other. I’m close to bursting point.

A man in a large red turban steps up.

“You will be requiring of a porter, sir?”

“What? No! Wait. Yes. Okay. Let’s go! I’ve got five minutes!”

The sprawling bodies moved for him (they never did for me).

Another queue. Another clerk. More disdainful looks. Obviously “special category traveler” doesn’t impress him, he sees them all the time. But I do finally get my ticket.

“You must be hurrying, sir,” the porter says.

“Where do we go now?”

“Please to follow me. Your name will be on the list.”

Scampering onto the platform. A huge steam-spewing behemoth faces me. Train lovers would melt at the sight. I’m far too tired even to look at it. We run together down the length of the train. The carriages are bulging with bodies. Second class looks like a turbulent Hieronymus Bosch fantasy. The porter pauses by long lists of printed names (nonalphabetical).

“Please to tell me your berth number, sir.”

“I’ve only just bought a ticket. My name won’t be on any list.” I was fed up with the whole ridiculous process.

“You do not have the reservation?” the porter asked with a worried frown.

“I don’t know what I’ve got!”

The porter looked utterly confused. Now I know I’m in trouble.

“Can you ask somebody?” I know it’s a dumb idea. The platform is one mass of jostling humans, not a uniformed official in sight. “Look,” I said, mustering all my remaining sanity, “is this a first class carriage?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well leave the bags here. I’ll work it out.”

He was obviously glad to be let off the hook and almost forgot to take his rupees before disappearing into the crowd.

Somehow—I actually don’t know how—I found myself being led to a seat in a six-berth carriage by a very plump and smiling guard, obviously used to the ineptitudes of foreign travelers.

I sank into my seat and closed my eyes.

“You have your bedding chit, sir?” Another official!

“My what?”

“Your bedding chit, sir. For your sheet and pillow.”

“You mean that’s not included?”

“Oh no, sir. That is extra, you see. You must have a chit.”

“Forget it. I’ll manage without bedding.”

“It gets very cold in this train, sir.”

I gave him ten rupees and asked him to do what he could to obtain bedding. The other five passengers were staring at me as if I were some kind of extraterrestrial being. I closed my eyes.

The train gave a great scream, whistles were blowing, doors slamming. Two hefty jerks, and it began to ease out of the station. I opened my eyes again. It was 7:30 precisely. I’d made it!

One of the passengers leaned over. “Ah, sir. You are from?”

“U.S.A. I’m from America.”

“Ah.” Five faces nodded expectantly.

“This is the Delhi train, right?”

“Delhi, sir?”

“Delhi, right?”

Much murmuring among the five faces. Oh, no! Don’t say I’ve got the wrong train. That would be the absolute last straw.

“I was told this was the Delhi express.”

Grins, laughter, and snorts. They all started talking at once.

“Well, yes, sir, that is the name, but I don’t think it is what you would call a true express, sir. Oh, no, not at all, sir.”

“Oh, no, by no means. Very slow train, sir.”

“You should have got the 10:30

P.M.

Much better, sir.”

“Oh dear, dear sir, you have a long journey. Very difficult.”

Who cares? The train’s moving. It’s going in the right direction. What’s a few extra hours? All I want is sleep anyway. I close my eyes again. My bedding man shakes my shoulder roughly. Another guard is standing beside him along with a large Indian businessman, looking very worried.

“This is not your seat, sir. It belongs to this man.”

“Well, this is the one I was given.” I felt utterly drained.

“The other guard should not have done this, sir.”

“Well, where is mine then?”

“I don’t know, sir. We have no record of your name.”

“Look, I’ve spent far too long waiting in lines for my ticket to be told you’ve got no record of my name.”

And then someone else started talking—a very angry, officious Britisher, pouring out pompous phrases about the chaos of Indian rail travel, the terrible condition of the stations, the abysmal attitude of the clerks, and the appalling ethics of guards who accept tips for obtaining bedding and don’t produce any—all topped off with a lot of froth about the climate, the food, the incompetence of petty officials…a real colonial tirade. A bit overblown, I thought, but certainly hitting all the bases—and eloquently. Surprise! Surprise! It was me doing the talking! A full, fulminating, postcolonial persona had suddenly emerged from my deep subconscious. I stopped him in full flow, wrapped him up, and popped him back. I didn’t like him at all. I was very embarrassed.

But it must have worked. I was left with my berth. The businessman shook my hand, and told me that other accommodation would be found for him. I began to apologize but he would have none of it. The porter appeared with my bedding. Someone helped me pull down the bed. The second guard returned to ask if I would like a cup of tea, which I gracefully declined. The five men in the carriage were very quiet, staring with some trepidation at this split-personality character in their midst. I smiled as charmingly as I could, bid them good-night, and slept the sleep of the gods through the long rocking night.

Delhi was a long way away but “Sufficient unto the day are the trials thereof.” In India it’s a good phrase to keep repeating to yourself, over and over and over again.

NEPAL—KATHMANDU

I had to come to hike in the high Himalayas. Another dream of youth. Every serious traveler has to journey to Nepal, at least once. True, there are other intriguing Himalayan destinations—Ladakh, Pakistan’s Hunza, Bhutan, Sikkim—but Nepal and its mystical top-o’-the-world capital, Kathmandu, always seem to have a special place in the hearts of world travelers.

I decided to fly from New Delhi. I could have roughed it with all the other backpacking trekkies and taken the notorious fifty-five-hour bus ride from New Delhi to Kathmandu but, as I was planning to return later by bus back to India, it seemed a waste of time (admittedly a rather contrived rationalization). And anyway I’d waited long enough to get there—twenty-one years, maybe more—so I felt I owed myself a celebratory form of arrival, a sort of fanfare flight for fantasies realized.

Prior to the flight I’d planned to stay overnight in New Delhi, but I’d forgotten the travails of travel in India. There was some kind of film festival going on in the city, and I couldn’t find a room anywhere. Even the $3.00 a night variety were crammed with Indian movie maniacs. So I thought, “When in Delhi…” and went to see a movie instead. An Indian movie.

The film was an enlightening experience. After two hours it showed no sign of ending. We’d gone through the full repertoire of the producer’s art—five murders, gory mayhem, fallings in love, fallings out of love, family retribution, a stickup, a punchup, three songs (they came out of nowhere for no apparent reason; the action just stopped, the fat lady sang, the action started up again), jealous wives, jealous husbands, faithful lovers, unfaithful lovers, a car chase, a car crash, a suicide, an odd little Arabian Nights dream-fantasy, two sex scenes (very delicately handled—the softest of soft porn), a comic character who kept falling down and pretending he was a dog, three gaudy sunsets, a fabulous banquet—in fact, a bit of everything for everybody, and still the damned thing kept going! The audience didn’t seem to mind at all. They laughed, applauded, wept, went out for sticky snacks, came back…

I’d had it and left.

I should have remembered a joke told me by an Indian businessman on a train between Varanasi and Jodhpur. (This came well after the traditional greeting: “Hello and how are you today and would you be so kind of telling me the country of which you are from and of which good name you are having and your special qualifications as a professional person and I hope you are well, thankyouverymuch.”)

“At a conference for press,” he began, “a pressman asked from a film producer, ‘Can you be telling the story of your latest film?’ Producer looks very surprised. ‘What are you meaning by “story”? Having you ever seen me make a film with any story? I have a special formula—a recipe for the success of my films.’

“‘And what is your recipe?’ said the pressman.

“‘It is very simple,’ says the producer. ‘One hundred grams of love affairs, two hundred grams of weeping and screaming, three hundred grams of violence, and four hundred grams of sex. I mix together well and my film is complete.’”

They make hundreds of these “recipe” films every year in India. Same characters, same basic variants of plot, running the same gamut of emotional highlights—and the same audiences. “Just keep ’em coming” seems to be the motto (usually at an average rate of eight hundred films a year).

The flight was on time and uneventful. A very odd circumstance in India. It was clouds, clouds, and more clouds—impressive formations, beautiful—but only clouds nonetheless. I’d hoped to see a bit of India from the air. This might be my only chance. But all I got was clouds.

An hour or so later something appeared on the horizon that looked like clouds but was too hard-edged. The color was the same, but the shadows were complex and striated.

Mountains! Glorious panoplies of snow-capped peaks towering above the clouds. The Himalayas. A vast white wall broken into sky-scratching diamond peaks, stretching across my window and all the way as far as I could see across the window on the other side of the aisle. Magnificent! Real lump-in-the-throat stuff.

At last—I was coming in to Nepal, until a few decades ago one of the remotest kingdoms on earth, closed to outsiders. And now, since the hap-hippie days of the sixties, a definite must-see for all true adventurers.

The energy of the place slams like a shock wave. I had no idea what to expect. Everyone I’d talked to who’d been to Kathmandu went sort of sloppy-eyed when asked to describe the place, rhapsodizing about its “special magic,” its justified reputation as “hippie heaven,” the way the city “just sort of hooks you.” They almost always ended sounding like born-again religious converts with phrases like “You’ll understand when you get there.” But they were right. Kathmandu is so overwhelming, so packed with images, that succinct summaries seem almost impossible—certainly inadequate. Like them, I’m tempted to say “You’ll understand when you get there,” but I suppose the role I’ve given myself requires a little more than that. Carefully measured prose wouldn’t do it though—at least not my prose—so all I’ve got left are my tape-recorded notes…shards of googly-eyed wonderments:

A green valley couched in hills and behind those hills, that line of bride-white peaks in the bluest of blue skies, not a cloud anywhere; tight-packed villages among the high terraces, perched like rock piles on the ridges…then sinking into the city, filigreed with spires and the tiered roofs of temples…you can feel it closing in…streets wriggling and narrowing the deeper you go, bound by houses and lopsided stores of raw sun-baked bricks…getting tighter now, old men sucking hookah pipes in shadowy doorways, women in black skirts with red-embroidered edgings, a child’s eyes, full of wonder, watching me from behind the ornately carved latticework of a wooden window screen; thick wooden doors into the houses, scratched and worn, with locks the size of jewelry boxes…smells of hot oil and baking

pauroti

bread…sudden pyramids of bright color—a spice seller on a corner, half hidden by his minimountains of turmeric, cardamom, cumin, and coriander…a swath of formal tree-shaded spaces as we pass the palace of Nepal’s King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev (the young Harvard-educated incarnation of Hindu Lord Vishnu) and past the fancy hotels and restaurants of Durbar Magh.Then back into a medieval tangle of alleys, muddy, unpaved…temples everywhere—cramped candled caves splashed with blood-red paint, shadowy gods inside, all glinting fangs and wheelspoke arms…noise—so much noise—crowds pressing against the cab as we drive deeper, past the flute sellers and the tanka shops and wood-carvers’ workshops and trinket carts sparkling with polished Gurkha knives, bracelets, heavy Newar jewelry…rickshaw cycles, winging like angry wasps through the throng…howled greetings from the peddlers—“

Namaste!

” (“I salute the God within you,” “Namaste—to you too.”) The gods are everywhere, holding up cornices, carved on the ends of protruding beams, peering from gaudy posters in store windows—scowling, smiling, fighting, snarling, or caught in the middle of erotic acrobatics…holy lingham shrines in dark courtyards, lit by smoky strands of light and wrapped in blood-red cotton sheets…more peddlers selling the skulls of long-dead monks decorated in silver, brass prayer wheels crammed with written prayers that you spin like a child’s toy and “make-merit” (

tamboon

) with Buddha all day long…fruit stalls piled high with apples, pomegranates, green oranges, grapes…a street of side-by-side dentists’ parlors overlooked by Vaisha Dev, the god of toothache, his shrine a mass of hammered nails (each nail a plea for pain relief)…bookshops galore—vast repositories of guidebooks and used books from the backpacks of trekkies and the social hubs of world-wanderer gossip…yak-wool jackets, very de rigueur with the “only-got-three-days” trippies…past the Rum Doodle restaurant (ah—Rum Doodle, the world’s highest fictitious mountain, ten thousand feet higher than Everest and subject of a wonderful travel book!)…We’re really stuck in the crowd now, hardly moving; I can read the notes and flyers pinned to every available post and door: “See the live sacrifices of animals for Kali—every Tuesday” “ENLIGHTENMENT NOW! Retreats in Buddhism, Massage, and Meditation. One day to three weeks…” “BUFFALO STEVE AND TERRY—I’m at the White Lotus Guesthouse. Leave note where I can find you guys for a few beers” “WE NEED URGENTLY—unwanted trekking equipment for staff to make follow-up visits to children living in remote areas of Nepal.”

We pass old hippies in dingy cafés sipping fruit-filled lassi and mugwort tea, playing with graying strands of matted hair, coddling their neuroses…a hundred brightly painted mandalas on laurel bark paper fluttering like summer butterflies…we’re really approaching something special, you can sense it, everything’s getting frantic—jugglers and boys banging on little

tabla

drums, saffron-cloaked monks with dye-daubed faces, ancient Hindu wanderers in dhotis carrying only wooden poles and mud-stained cotton bags, the spacy faces of old-young hash-heads…all crammed in this alley of Hobbit houses piled high on one another, leaning and cracked, beehived with tiny rooms, ladder staircases, encrusted with carved-wood images of tiny gods and peacocks and Byzantine tracery…surely it can’t get any more claustrophobic than this—a sweaty tangle of bodies, trishaws, street markets, hooting cabs, howling peddlers, and grimacing gods…this is too much…I’m suffocating…

Then, like a torrent tumbling off a precipice, we’re all suddenly spewed out into the living heart of this crazy place, a great sprawl of spaces and shrines and palaces and monasteries and pagoda-roofed temples, soaring into the sunlight with bells and gongs and cymbals and all the wonderful clamorous cacophony of Kathmandu’s throbbing center—the great Durbar Square itself—ending place of pilgrimages, center of enlightenment; the most wondersome place in the world!

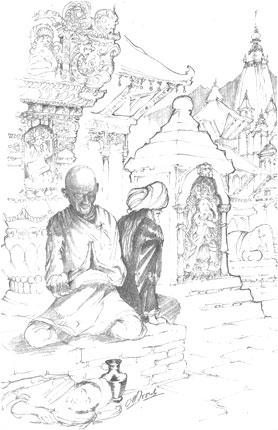

It’s a dream. I’ve never seen anything like it. I leave my cab and wander across the stone-paved plazas like a gawking child, openmouthed and oggle-eyed. Everywhere are the encrustations of excess—expressions of the tangled complexity of Nepal’s Buddhist-Hindu heritage—great sculptured orgasms of carved stone and wood and gold-spired stupas and chedis and arched doorways buckling with the weight of swirling decorations—and everything splattered with red

sindur

(red dye mixed with mustard oil) or betel nut juice stains and the piled detritus of rice offerings and ashy incense sticks and melted candles, all in a soaring forest of tiered buildings, swooped by flights of white doves, sparkling against a high blue sky.

It’s too much. You need days to begin to understand all the riches and symbols and intracacies of this place where everything has a meaning, a significance (no empty Rococo decoration-for-decoration’s sake here). The images just keep piling up like the carved layers of the shrines. I caught a glimpse of the tiny living goddess—the Kumari—peeping out of the ornate wooden windows of her chamber in the Kumari Bahal. Selected as a child, she is considered to be the incarnation of the virgin goddess, Kanya Kumari (just one of the sixty-three various names given to Shiva’s shakti, Parvati), and maintains her status until her first period, at which time she becomes mortal and is replaced by another god-child whose horoscope aligns with that of the king. Official forays from her palace are limited to religious festivals when she travels in an elaborate chariot and is carried everywhere to prevent her feet from touching the ground.

White, red, and gold temples are everywhere—the soaring extravaganzas of the Taleju, the Degu Taleju, the octagonal Krishna Mandir (the ferocious black figure of Kal Bhairav, holding a skull as an offering bowl, lurks here behind a huge lattice screen), Narayan, Shiva-Parvati, Jagannath. And beyond, in all the teeming alleys leading to Durbar, are hundreds more temples and shrines.

In the misty distance, on a hill at the edge of the city, I can just make out the great white stupa of Swayambhunath, topped by a golden spire and the all-seeing eyes of Buddha. Here, among the incense and gongs and bells and spinning prayer wheels and bowls of burning oil and pushy peddlers, scores of monkeys frolic while Tibetan Buddhists transact precise rituals on this sacred site, more than 2,500 years old.