Back of Beyond (37 page)

“What do you think they’re waiting for?” I finally asked my friend.

“Something,” he whispered mysteriously. Then he giggled softly. “Anything.”

More sitting. Now my arms were numb too. I was hungry and hot and thirsty. And bored.

“I think I’m ready,” I whispered. I’d never make a guru lover. A bit of meditation once in a while is all right, but I suffer from an overactive brain and an underdeveloped sense of patience.

“Yes. We’ll try another one.” Even my friend seemed perplexed by all the silence.

“They usually talk more,” he explained as we rejoined the throng. “He was one of the silent ones.”

As the heat and dust rose together and the crowds grew thicker, silence became hard to find. This was a strange affair—part carnival, part religious revival, part showcase for the nation’s cream-of-the-crop gurus. A high-hype commercialized religious romp—or something else?

My Kathmandu friend had lent me one of his religious books, a delightful nineteenth-century account of an English Victorian woman’s wanderings with a swami in the Himalayan foothills. I sat with my new friend in the shade of an empty canvas tent as the crowds milled by and read a few fragments of Sister Nivedita’s (her Indian name, given her by the swami) truth-seeking experiences:

So beautiful have been the days of this year. I have seen a love that would be one with the humblest and most ignorant, seeing the world for a moment through his eyes. I have laughed at the colossal caprice of genius; I have warmed myself by heroic fires and have been present at the awakening of a holy child…my companions and I played with God and knew it…the scales fell from our eyes and we saw that all indeed are one and we are condemned no more. We worship neither pain nor pleasure. We seek through either to come to that which transcends them both…only in India is the religious life perfectly conscious and fully developed.

I looked up. Among the crowds were the occasional Western faces, the faces of seekers, coming to the mela to find answers to all the mysteries, coming to find comfort, coming to “play with God,” coming to experience the “perfectly conscious religious life.”

Singing, chanting, dancing and discordant sitar sounds exploded from a score of pavilions. Babies rolled in the sand while sari-clad mothers washed and polished huge copper rice cauldrons at the water taps; ancient hermitlike men displayed themselves in the most contorted positions in little tents with hand-painted signs nailed to bamboo posts: “Guru Ashanti has sat in this same position without moving for eight years.” “Rastan Jastafari eats only wild seeds and drinks one glass of goat’s milk every 8 days to the honor of Shiva.” A fairground of fakirs! There were men with necklaces of cobras and pythons; a troupe of dancing monkeys playing brass cymbals; more fortune-tellers with their little trained birds; peanut vendors; samosa stands, reeking of boiling oil; groups of gurus huddled together deep in gossip (“So what’s new in the enlightenment business, Sam?” “How’s your new ashram going, Jack?” “Harry, can I borrow your cave up on Annapurna for a couple of years?”)

There were special compounds for Tamils, for Tibetan refugees, for Nepalese pilgrims from the high Dolpo region of the Himalayas, for ascetic members of the Jain religion, and a hundred other far more obscure sects.

Sometime in the middle of the afternoon a scuffle occurred near the river. A bronzed Swedish cameraman had just had his expensive video camera smashed into bits of twisted metal and broken computer chips by a crowd of irate Bengali tribesmen. Generally everyone seemed to tolerate cameras and tape recorders but this unfortunate individual had broken some taboo of propriety and now stood towering head and shoulders above his antagonists, gazing at his ruined machine in disbelief. The police arrived, then the army, and together they formed a flying wedge to rescue him, while the shouting, cursing, and spitting roared all around them.

“You have to be very careful,” my friend whispered. “You never know what can happen here.”

A few minutes later there was another commotion on the far bank. Thousands of dhoti-clad bathers were running around, shouting and pointing at the fast-flowing river. Loudspeakers were urging calm and I could see another phalanx of police and soldiers scurrying down the dusty slope to the water where they stood helplessly gazing at the water. Stories spread like a brush-fire through the tent city. Someone had been lost in the river. An old woman, a young child, a famous sadhu—someone—had stepped beyond the cordoned-off section of shallow water into the main flow of the current, eddied with whorls and churning froth. He, or she, had been caught in the undertow and had vanished. People strained to spot the body. But mother Ganges swirled on, India’s eternal stream of life and death, filled with the ashes of cremated bodies, bestowing fertility on the flat lands, rampaging over them in furious floods, swirling and whirling its way from the glaciers of the high Himalayas to the silty estuaries of the Indian Ocean. Omnipresent, indifferent, endless.

My friend had to leave (suitably rewarded with rupees and two rain-stained copies of

Newsweek

“to improve my English”). I sat on a bluff overlooking the merger of the two rivers. The sun sank, an enormous orange globe squashing into the horizon, purpling the dust haze, gilding the bodies of the bathers.

The moon rose, big, fat, and silver in a Maxfield Parrish evening sky. There were thousands of people by the river now. The bathing increased but everything seemed to be in slow motion. I watched one old man, almost naked, progress through the careful rituals of washing. He was hardly visible through the throng and yet he acted as if he were the only person there by the river, unaware of everything but the slow steady rhythms of his cleansing. After washing every part of his body he began to clean his small brass pitcher, slowly rubbing it with sand, polishing the battered metal with a flattened twig, buffing its rough surface with a wet cloth, until it gleamed in the moonlight. Then he disappeared and other bodies took his place by the river.

I sensed timelessness and began to feel the power of this strange gathering. Each person performed the rituals in his or her own way and yet from a distance there seemed to be a mystical unity among all of them, all these souls as one soul, cleansing, reviving, touching eternity in the flow of the wide black river, linking with the infinity, becoming part of the whole of which we are all a part.

I made my way slowly to the river and knelt down. For a moment there was no me left in me. The river, the people, the movements, the night breeze, the moon, life, death, all became as one continuum. A smooth, seamless totality. An experience beyond experience. A knowingness beyond knowledge.

I washed my face and arms and let the water fall back to the flowing river where it was carried away into the night.

INDIA—THE RANN OF KUTCH

Close your eyes and imagine the utter emptiness. A white nothingness—a brilliant, frost-colored land—flat as an iced lake, burning the eyes with its whiteness. Not a bump, not a shrub, not a bird, not a breeze. Nothing but white in every direction, horizon after horizon, on and on for over two hundred miles east to west, and almost one hundred miles north to south.

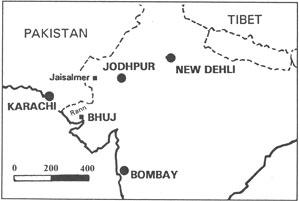

This is the Rann of Kutch (or Kachchh), the largest area of nothingness on the planet; uninhabited, the ultimate physical barrier, separating India from Pakistan along its far western border. Only camels can cross these wastes, and at terrible cost. During the monsoon seasons it’s a shallow salt marsh, carrying the seasonal rivers of Rajasthan slowly out to the Arabian Sea, just south of the great Indus delta of Pakistan. Then for months it’s a treacherous quagmire of molasses mud under a brittle salt skin. Periods of safe crossing are minimal. Occasional piles of bleached bones attest to the terrors of this place. Tales of survivors, reluctantly told, are unrelieved litanies of human (and animal) distress. There is life out here—herds of wild asses the size of large dogs and vast flocks of flamingoes encamped in mud-nest “cities”—but very hard to find.

“It is a strange place.” An old man in one of the baked-mud villages on the southern edge of the Rann had finally agreed to talk about the place through a local interpreter.

“I crossed the Rann many times when I was a young man. Now the only people you will find on it are people carrying drugs or guns. The army tries to stop this trade”—he flung out his small, cracked hands—“but what can they do? The Rann is so vast, the army cannot always use their trucks or their jeeps. They get stuck in the mud, even in the dry season. You can never trust the Rann. Every year it is different. It is very hard to know which way is safe for a crossing. One year”—he paused and studied the endless horizon—“many years ago, I lost my brother and eight camels. He was not so experienced as I was and we had a disagreement. I told him we had to go the long way because the monsoon had been late and the mud was not dry. But he was in a hurry. His family was very poor…” The old man smiled sadly, “We are all poor but he wanted to buy land and build his own house…he was in a hurry.”

He paused again and we all sat staring at the shimmering whiteness. Even the sky was white in the incredible heat. “He was a good man. I was his older brother. He should have listened to what I told him.” Another long pause.

“What happened?” A stupid question. I knew the answer.

The old man shaded his eyes. “He has his eldest son with him, twelve years old. A fine boy…”

There was a wedding in the village. We could hear the music over the mud-walled compound. Later there would be a procession and a feast of goat, spiced rice, and sweet sticky cakes.

“He went a different way?”

The old man looked even older. His face was full of long gashed shadows.

“You must go to the wedding,” he said. “They will be proud if you go. Not many people like you come to this place.”

“I’ve been already. But I think it made people a bit uncomfortable. I seemed to attract more attention than the bride and groom. One man looked quite offended, a man in a bright blue suit.”

He laughed. “Ah! Yes. I forgot he was coming. He is with the government—very important. He likes to take charge of things…just like my brother.”

“So what happened to your brother?”

The old man shrugged. “He took the wrong path. We found two of his camels on our way back. They were almost dead but we brought them back home to our village.”

The music of the wedding faded. It was hard to find shade from the sun. I looked across the Rann again. Almost one hundred miles to the other side, with no oasis, no water, no shade, just this endless salt-whiteness.

“He could have reached the other side. Maybe he decided to stay for a while?”

“His family is here. His wife and his children.”

“Maybe the army arrested him?”

“No, this was nine years ago. The army was not here so much at that time.”

“So you think he died.”

The old man drew a slow circle with his finger in the sandy dust.

“He became a ‘white,’ like so many others.”

“A ‘white’?”

“We call that name for men who do not return from the Rann. Part of their spirit remains in the Rann. There are many, many of them. Who can tell. Maybe hundreds of men. Hundreds of whites.”

“Back home we call them ghosts—the spirits of the dead still trapped on earth.”

“Yes I know about your ghosts. Here it is a different thing. We are not afraid of the whites. When we cross the Rann we remember them. They protect us. Sometimes they guide us.”

“But you never see them?”

The old man smiled and spoke quietly. “As I told you, the Rann is a very strange place and you can see many strange things…it is difficult to explain. The Rann is not like other things on earth—not even like other deserts. It has its own nature and if you listen and look and think clearly, you will be safe…”

“Your brother didn’t listen?”

“He was a good man but much younger than I. And he had many worries. His mind was full of many things. He could not hear clearly.”

“Do you think about him a lot?”

“He was my only brother. We had five sisters. But he was my only brother.”

“So, in a way, he’s still here.”

“Of course. He is a white. He will always be here.”

My long (very long) journey to the Rann began on the Nepalese-Indian border, in the gritty, noisy little town of Birganj. Sixteen hours of bone-crushing bus travel had brought me south from Kathmandu, over the passes and down through the gorges, and deposited me at this nonentity of a place. We were late arriving, not a particularly surprising occurrence in a land where precise bus schedules bear little relevance to reality.

“Sir, please be on time, sir.” I had been instructed in Kathmandu. “At six-oh-three

A.M.

, sir, the bus will leave the square, and you must present your ticket ten minutes before departure, sir, otherwise there may be many difficulties.”

I had left my warm bed near Durbar Square, one of the most overwhelming urban spaces in the world, and arrived in another chilly fogbound square to find no sign of the bus at its alloted space. It was very dark and wet, and repeated inquiries always brought the same inevitable smile and shrug—the Nepalese equivalent of our “no-problem” response. But for the initiative of one small boy who told me the departure point had been moved to the other side of the square (I couldn’t even see the other side in the cloying gloom), I would have missed the bus and been obliged to start the whole rigmarole of ticket buying all over again.

The ride began with the barefoot bus driver praying to the various Hindu deities that decorated his tiny cab, and then rapidly deteriorated into a series of Looney Tunes crises, each more potentially disastrous than the previous one. The cyclist we ran into, a pothole we hit the size of a mine shaft, and the fruit seller’s cart we spilled to avoid a cow, were mere warm-ups to the chicken runs against mammoth Mack trucks, the race against a still-sliding landslide, the near spill into a sixty-foot gorge when a section of roadbed gave way, and the ultimate fury of our driver, who leaped out of his cab to confront another driver traveling at sloth pace up a steep ravine (only he forgot to set the handbrake first!).

All I wanted when we finally arrived in Birganj was a simple bed and sleep. A simple bed came easily enough (a square of plywood and a sheet in a freezing cold $3.00-a-night hostel), but sleep was hard to come by in a room also occupied by an enormous Australian earth gypsy whose snoring seemed to shake plaster off the walls and made the windows rattle. Haggard and dizzy with fatigue in the early dawn, I tried to sort out my papers for the border crossing while he insisted on telling me hard-luck tales of his injuries, illnesses, and illicit dealings, all the way from Darwin (“best place in the land of Aus, mate”) to Dar es Salaam. His pessimism and chronic dislike of almost everyone he’d met and everything that had happened to him made me wonder why he bothered traveling at all. His ultimate tirade was directed at “that bunch of bastard wogs” in Bombay who had managed to relieve him of all his worldly possessions except his sleeping bag and had even run off with his money belt crammed with dollars from some emerald-smuggling escapade in Malaysia. The air was purple with his profanities, and I was tired of him.

“Isn’t there one single place you’ve enjoyed?”

His mood changed. The swearing and cursing subsided, and this hairy giant of a man became almost teary-eyed as he told me about Bhuj, the idyllic Gujarat coast (“Not a bloody soul for miles. The best beaches in India, mate. No one ever goes there.”) and the mysteries of the Rann of Kutch.

So, thank you whatever your name is; I forgive you your snoring and your jaundiced outlook on life and your self-pitying tirades, and will remain ever grateful for your introduction to this truly fascinating corner of India.

Now the only thing I had to do was get there.

Traveling by bus is the only real way to experience India. You just lean back (actually leaning is a rather difficult thing for the average-sized Westerner because of the cramped space between the seats), stop trying to drive the bus in your mind (you couldn’t anyway—it takes total Indian logic and faith to negotiate even the quieter country roads littered with tractors, cattle, bicyclists, lines of basket-carrying pedestrians, and wild dogs. And as for the towns—forget it!), and let the whirligig of impressions roll by. Here’s a transcript of one of my tapes, a bit garbled, but I think it captures the flavor of bus travel in India well enough:

…a truck on its side in a hole in the road, didn’t he see it, did it just open up? We’re slowing down to get through all the spectators; kids are selling us Cadbury’s chocolate bars, newspaper cones full of peanuts for three cents…here’s a woman with enough branches and lumps of wood bundled on her head to break the proverbial camel’s back…a guru-seeking English couple behind me speak in pungent epigrams, out-Zening each other (one-up-Zenship?)…a cartoon sign indicates that spitting is prohibited on the bus so everyone’s hacking and spitting…enormous dew-covered spiders’ webs in the bushes by the roadside…behind another bloody white cow again in the middle of a twelve-foot-wide road and all the driver’s honking doesn’t make any difference at all…now he’s put the tape back on, the same one of Indian music we’ve had for hours and hours over the same cracked speaker. It seems to keep changing speed—or is that the way it’s meant to sound?…ah, stopping again. The beer isn’t bad. But I can’t take any more dhal bhat and curried eggs. A glass of mango lassi—beautiful. This is nice and crunchy—what is it? I said what-is-it? Little birds. Sparrows. Oh boy…off again now past a street market under umbrellas—six men in a line operating sewing machines; open-air dentistry—that’s novel; a barber plucking out nose hairs one at a time; bright-painted pedal-cabs all over the place; piles of beautifully ornate saris on a table; a herd of goats gone crazy; the smell of little bits of dough deep-frying in an old oil drum over a pile of red hot charcoal…cabs like tiny temple shrines dripping with ornaments…elaborate washing rituals at roadside taps—such a concern with cleanliness, especially the feet…towering posters for Indian films (you can spot each of the ritualized characters a mile away: the black-faced villain with scimitar mustache; the lovelorn hero; the shy, modest heroine; the plump, plotting matron; and the comic—there’s always a comic)…piles of lemons and limes for sale on the steps of a very old and very lopsided temple…a riverbank smothered in drying laundry…drying chilies on rooftops, brilliant reds…odd little dog kennel-sized stores selling pens, cigarettes, matches, combs, perched on platforms supported on four wobbly wooden legs (temporary businesses, no property taxes?)…signs everywhere for Campa Cola, Thumbs Up Cola, Frenzi ice cream…latticed beds by the roadside for sleepy store owners…so many, many people. You never seem to get away from crowds…we’re playing chicken again with a truck, the road’s only wide enough for one of us, he’s coming straight for us—jeez—c’mon pull over—wow! How the hell did we miss him?…the bus driver’s mate leaning out and shouting at the truck driver, banging instructions in code on the side of the bus (one for watch out; two for

watch out!

, three for what?). Too late, we’ve hit it (only we never hit anything, or at least nothing that we notice. It’s like magic. A constant barrage of inevitable accidents that never happen).Out in the country again, very flat, rice paddies I think; a few mud houses with round cow dung patties drying on the walls…men performing their most intimate toilets out in the open fields, trousers down a short way, chatting to one another…a teacher sitting cross-legged on a stool outside a mud-walled school lecturing to a class of thirty, forty children…a swarm of preschoolers, gleefully naked, frollicking in a green pool…the body of a very old man dressed in rags and clutching a long pole at the roadside. (Is he dead? We miss him by inches and he just lies there.) A sense of all these scenes repeated endlessly across all of India, beneath a patina of colonial organizational officialdom that has long since clogged up and atrophied—and yet—still a vitality here, a frazzling pace of life, colors, laughter, variety; an acceptance of the unchanging nature of things; a calm in the midst of unending chaos…I’m worn out just watching it all—it’s like a TV docudrama. How would I feel if I were actually out there, in it, trying to do something, to accomplish something…?

Gandhi marveled at all this energy. What was it he said? Something like “We must be Indians first and Indians last.” Well it looks like he got his wish. India flows on and on, as Indian as it’s always been and possibly always will be, at least in these vast hot heartlands. And another telling quote, this time from Rudyard Kipling: “And the epitaph dear: A fool lies here who tried to hustle the East.”

It was rather sneaky of me. But I couldn’t resist it. The zap-Zening of the English couple I’d heard in the seats behind me had merely been a preparatory duel, a prologue to the real battle. I could sense the tension. So could the Indian passengers, although they couldn’t understand a word of their brittle exchanges. I was tempted to turn around and study them but that would have to wait. The contest was about to begin—a mutual masterpiece of bickering between two lovers who may have known and loved each other a little too long: