Bad Little Falls (7 page)

Authors: Paul Doiron

I could understand why my friend Charley Stevens had wanted me to meet Kendrick. If even half his exploits were true, he definitely deserved a profile in the

New York Times.

And if he knew the wilds as well as I suspected, then he might prove useful to me down the line. Still, something about the self-styled mountain man rubbed me the wrong way: His confidence seemed to border on monomania.

I hadn’t seen much of Charley and his wife, Ora, over the previous months. They’d been forced to leave their beloved cabin in western Maine when a real estate developer bought the land out from under them. Ora had written a lovely note to offer me consolation after Sarah moved to D.C., and she promised to invite me to dinner at their new home, but so far, that hadn’t happened. Every few weeks I’d get a call from Charley, who wanted to chew over some gristle of news, but he often seemed preoccupied by issues he wouldn’t discuss, and I had the good manners not to ask what was troubling him.

I’d never made friends all that easily. After the evening at Doc’s, it was safe to say that dinner parties with veterinarians and dogsledders would not become the basis of a satisfying new social life, either.

* * *

Everyone has heard the old saying that the Eskimos, or Inuit, have umpteen different words for snow. The idea is that they live closer to their environment than we do and thus have not lost the ability to differentiate among the multitudinous forms freezing precipitation can take. Where we see snow, the Inuit see subtleties.

This charming legend, like most charming legends, is false. The Inuit have just about as many words for snow as do English speakers; they just tend to combine their terms in certain ways to add specificity to their meteorological conditions.

I have no doubt, however, that the Inuit recognize the difference a few degrees in temperature can make in shaping a snowflake. Warmer weather means wetter snow. Wet snow is heavy; its weight shatters tree branches. It clings to power lines and brings them crashing down. On the road, it turns to slush and sends tractionless cars skipping into ditches. Wet snow melts quickly in your hair and runs down the back of your neck. It follows you into your house by riding in the treads of your boots and leaves puddles to mark its passage. I know this because, like the Inuit, I live mostly outdoors in the winter.

Because of the low-pressure front pushing down from Canada, the snow that was falling in the road was not wet, but in fact very dry. The wind whipped it around like white sand in a white desert, forming metamorphic dunes and ridges that changed shape while I watched. Dry snow carries its own dangers. It clings to nothing, not even itself, and is so light it can be stirred by the faintest breeze, turning a black night blindingly white. Weightless, it resists plowing and shoveling. It covers your tracks in the woods, making it easier for you to get lost, and because dry snow is the harbinger of subzero temperatures, it makes losing your way a potentially life-threatening mistake.

I’d been on the road for fifteen minutes or so when my cell phone rang in my coat pocket. The number on the display told me that the caller was Larrabee.

“Doc? What’s wrong?”

“My neighbor Ben Sprague just called. He and his wife, Doris, just had someone show up at their door, frozen solid. They want me to come over and have a look at the guy. It sounds like he’s in rough shape. Would you mind heading back this way? I’m in no condition to drive.”

“Where’s Kendrick?”

“He’s going to head over to the Spragues’ on his dogsled.”

“I’ll be there as soon as I can.”

“It sounds like that poor fellow is in rough shape,” Doc said again for emphasis.

Without a second thought, I did a slow U-turn and began creeping through the blizzard to Doc’s farmhouse.

I found him at the foot of his drive, bundled up from head to toe, with only the tip of his nose and his fogged-over eyeglasses exposed. He wore an Elmer Fudd–style hunting hat with the flaps buttoned under his chin, and he’d wrapped a scarf tightly around his mouth and beard. He was toting his black doctor’s bag again. I wondered what medicine or instruments a veterinarian might possess to treat a human being for frostbite and hypothermia.

He climbed in beside me, set his leather bag on his knees, and pulled the safety belt tight across his chest. “The Bog Pond Road is up here on your right,” he said. “Look for the tall mailbox.”

The tall mailbox? Soon enough, I saw a candy-striped pole sticking up from a snowbank. Nine feet up in the air, a mailbox was balanced on top of it. The words

AIR MAIL

were painted on the side—someone’s idea of a real knee-slapper.

The Bog Pond Road was in considerably worse shape than the main drag. You would have believed it had been months since a plow truck last visited. The snow was piled above the headlights of my Jeep, yet somehow we managed to push through the drifts without getting stuck.

We passed a darkened trailer that seemed to have been abandoned for the winter, then another ranch house with boarded-up windows.

“What’s that noise?” asked Doc.

“Where?”

The raging wind was so loud, I almost didn’t hear the snowmobile. A single yellow light, like a bouncing lantern, showed in the dark ahead of us. While we watched, it grew larger and larger, brighter and brighter. Some fool was riding his sled straight down the middle of the road.

“Can’t he see us?” asked Doc.

I let up on the gas and engaged the clutch. The Jeep crunched to a halt.

The snowmobile seemed to be accelerating as it drew nearer.

Larrabee pushed himself back against the seat and straightened his arms against the dash. “That idiot is playing chicken!”

I clenched my molars, but at the last possible moment, the snowmobile veered off to our right, narrowly missing a row of spruces that ran down the hill. I caught a glimpse of a goblin-green sled with a person dressed in the same color snowmobile suit. Then the rider disappeared into the darkness behind us.

“Who the hell was that?” said Doc.

Unbidden, the face of Barney Beal popped into my head. “I don’t know,” I said, “but he’s going to wrap himself around a tree if he keeps that shit up.”

I put the Jeep into gear. The wheels spun and the vehicle began to shake like a dog just emerging from a cold lake. We were going nowhere fast.

“The Spragues live at the bottom of this hill, not far from the Bog Stream bridge,” Doc said. “We can walk there.”

While Larrabee waited, I grabbed a few supplies. I pulled a halogen headlamp over my Gore-Tex cap. I dumped ice-fishing tip-ups out of an ash pack basket. I found a wool blanket and a wilderness first-aid kit.

When I looked up with the dancing beam of the headlamp, I saw Doc hurrying down the road in the dark. The liquor in his system had already done a number on his judgment.

“Hold up, Doc!”

I pulled the straps of the wooden pack basket over my arms and retrieved my snowshoes from the Jeep. I slid my boots into the bindings and tightened the rawhide cords. Then I started off down the hill.

Larrabee moved pretty fast for a half-drunk man plodding through thigh-deep snow.

The Spragues’ house was a little chalet with a steeply pitched metal roof, which allowed heavy loads of snow to fall off. The outside lights were all switched on, bathing the scene in an elfin glow. I saw an old Subaru station wagon hiding against the side of the house, out of the wind, and two new-looking Yamaha sleds—his and hers—parked nearby. There were new tire tracks and a wedge-shaped snowbank that indicated a pickup had recently plowed its way out of the dooryard.

By the time I got to the door, Doc was already standing inside, unlooping the scarf from around his whiskered chin.

A squat little woman was standing beside him, looking back at me with an expression of alarm. She had short hair, dyed a sort of maroonish brown. A rosy line of blood vessels ran from one cheek up over the bridge of her nose to the other cheek. She wore a mint-green sweatshirt with a moose on it and jeans with an elastic waistband.

“Doris, this is Mike Bowditch with the Maine Warden Service,” Doc said.

“Thank goodness you’re here!”

“Where’s your visitor?”

“In Joey’s room.”

She led Doc into the back of the house while I struggled to escape my snowshoes. I tried kicking off as much of the powder as I could in the mudroom, but a wet white trail followed me down the hall.

The house didn’t seem dirty so much as unkempt. On the walls hung amateur oil paintings in the style promoted by those learn-to-paint television shows. But they were all crooked. The odor of an uncleaned litter box drifted from some hidden place.

In a boy’s bedroom, Doris Sprague leaned against one wall while Doc bent over a young man stretched on top of a narrow bed. He wore a faded denim jacket with a shearling collar, an untucked flannel shirt, baggy jeans, and motorcycle boots with silver buckles. His wet chestnut hair was plastered over his ears and across his forehead. He might have been handsome once, but now his face was horribly splotched and swollen. Waxy yellow patches of frostbite covered his entire nose and both cheeks. His fingers were bent into steel-gray claws.

“Young man,” said Doc. “Can you hear me?”

He snapped open his eyes. The pupils were the size of dimes. “No.”

“I’m a doctor,” Larrabee said calmly. “I’m going to help you.”

Doc had a pretty good bedside manner, considering his patients were mostly cows and horses.

“I’m calling an ambulance,” I said.

“Ben already did,” said Mrs. Sprague.

“Do you know who this man is?”

“I’m not sure. His face is so…” She hugged herself and shivered, as if the man’s hypothermia were contagious. “His wallet is over on the table. I tried to cover him with a blanket, but he keeps saying he’s hot.”

“Press,” said the man.

“What’s that?” asked Doc. “Press what?”

“Presster,” said the man.

“Is that your last name or your first name?” Doc asked.

I opened the wallet and pulled out the driver’s license. The picture showed a good-looking version of the disfigured face before us. He had high cheekbones and feathered chestnut hair cut like a disco dancer’s from the 1970s.

“His name is John Sewall,” I said.

FEBRUARY 14

It’s snowing wicked hard out tonight. I’m writing this under the covers with the headlamp Aunt Tammi gave me for my birthday.

THIS IS MY

LAST

WILL & TESTAMENT

I bequeath everything to Ma except my Bruce Lee poster. Give that back to Dad.

And Tammi should get my headlamp, I guess.

I want to be buried at sea or burned like a Viking. Either way is fine.

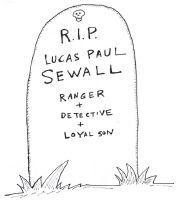

On my tombstone it should read—

I hear something.

WHISPERING!

It ain’t the wind. That’s a voice speaking. A woman’s voice.

SHE’S HERE!

8

Should I have made the connection between the face on the driver’s license and the incident I’d witnessed at McDonald’s? It’s easy now to say yes. In my defense, I hadn’t focused on the smaller of the two men. My attention had been fixated first on the jaw-droppingly beautiful woman behind the counter and later on the tattooed thug. I’d barely noticed the big one’s sidekick, and the name Sewall—like Beal, Cates, or Sprague—is common in eastern Maine.

From his knees beside the bed, Doc looked up at Mrs. Sprague. “Doris, I need you to bring me all the blankets and sleeping bags you have in the house.”

The solid little woman embraced herself tightly. Her eyes had a glassy sheen. She seemed to be in a trance. “What did you say?”

“We need to wrap this man up in as many warm layers as possible. I’m barely getting a radial pulse.”

“Should I run a hot bath?” she asked.

“Christ no. He could have a heart attack from the shock.”

She began blinked rapidly. “I’m sorry! I didn’t know.”

“It’s all right, Mrs. Sprague,” I said. “Let me help you.”

Hypothermia is a decrease in the body’s core temperature to the degree where the entire cardiovascular and nervous systems collapse. The only way to treat it is to warm the afflicted person up gradually. Hospitals pump humidified air into the lungs and irrigate body cavities with warm liquids, but these methods were beyond our capabilities in the little Swiss chalet. The best we could do was wrap up Sewall like a burrito in as many layers of insulation as we could find.

I followed the woman from room to room, gathering up every Navajo blanket, down sleeping bag, and cotton sheet in the place. Doris Sprague found a hot-water bottle for me and began to fill it with water from the kitchen tap. We would apply it to Sewall’s armpits or his groin, above the femoral artery.

I brought the accumulated bedclothes into the room with the frozen man. It was obviously a teenage boy’s bedroom. A bureau held various sports trophies (baseball and basketball) and assorted animal teeth and skulls. There was a picture of the pop singer Katy Perry on one wood-paneled wall; on another was a poster of an airbrushed-looking wolf, which was staring out at the room with the same intensely blue eyes as Ms. Perry’s. The poster bore the slogan

IN

WILDNESS IS THE

PRESERVATION OF THE

WORLD.