Banana (16 page)

Authors: Dan Koeppel

Aguilar took me into a brightly lit room and asked me to remove my shoes. “This is a nursery,” he said. “No contamination.” The space contained row after row of test tubes, with tiny banana plants in various stages of early growth: some just a few filaments snaking down into the liquid, others with fingernail-sized green leaves.

Aguilar narrowed the odds for me again. “Most of these,” he said, “will either not grow at allâor they won't grow right.” The plants that do will eventually be taken out to a greenhouse and then, when they're big enough, be planted outside. The percentage of plants that make it to the field? Here's the math: one seed for every ten thousand bananas. One percent of those seeds actually produce an embryo that's viable. And the total odds of getting a banana to the greenhouse?

One million to one

.

It isn't over then. That lottery long-shot banana still has work to do: Once that plant is fully grown, it is thrown back into the unprotected field. If it survives, if a needed quality appears, the process repeats, generation after generation, over a period of years, with each new banana begetting another. Many of the varieties Rowe began breeding in the 1960s are still being examined, still being perfected.

Almost fifty years have passed since the time Rowe began the program that is today run by Aguilar. During that time, La Lima's researchers have come up with between twenty and twenty-five viable banana varieties. Some of those are being grownâthey're suitable for limited, local consumptionâin Cuba, Brazil, and parts of Africa. That's a huge success story, given the odds.

But how many of Rowe's progeny got close enough to be considered as a Cavendish replacement?

Just one.

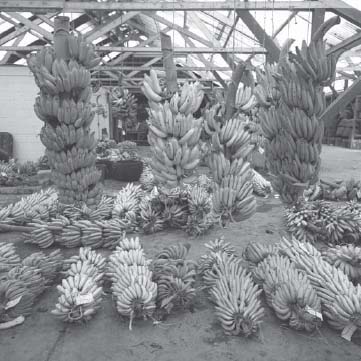

Phil Rowe's legacy: man-made bananas,

bred over four decades in Honduras.

29

A Savior?

U

NITED FRUIT LAUNCHED THE ATTACK

on Jacobo Arbenz from Honduras in 1954. But that country was at the same time embroiled in its own banana conflict. A month after the soon-to-be-deposed Guatemalan leader presented United Fruit with a tax bill, a few dozen Honduran workers walked off the job. By the end of the month, the nation's entire banana industry was frozen in place: Thirty thousand workers refused to enter the plantations, loading docks, and railroad depots.

The Honduran economyânever strongâwas on the verge of collapse, and the banana exporters, already in a state of panic over Guatemala, were terrified that the strikers would succeed and that one Central American country after another would then fall. To lose control over their holdings as Panama disease was reaching its coup de grâce was unthinkable.

United Fruit acted first in Guatemala because it was easier to stage an overthrow in a country without strikers than to attack tens of thousands of angry, idled laborers. But the company also knew that success against Arbenz would shift momentum away from the envisioned chain reaction. That's exactly what happened. When the Guatemalan government folded, the morale of the Honduran strikers collapsed, and the country's government was able to arrest labor leaders by accusing them of having ties to Arbenz. The biggest banana strike in history ended four days after the Guatemalan president went into exile.

YET VICTORY TURNED OUT

to be a difficult thing to claimâand to hold on to. Honduran workers had accomplished something just by generating such a large number of strikers. That tiny margin of success would resurface a few years later in an even more powerful attempt by banana workers to gain control over their own destinies.

Between 1954 and 1958, Hondurasâwhich since the turn of the century had teetered in what seemed to be a permanent state of instability thanks to constant intervention by banana interestsâhad one president who never took office; a vice president who became president then quickly attempted to extend his rule into dictatorship; and two military coups, one that failed and one that finally succeeded in 1956. The Honduran army would control the country for decades; the effect on the nation's citizenry, economy, and industries would be to veer between extremes, depending on what particular faction ruled. Honduras would have good times and terrible times, looking sometimes like a sleepy, impoverished republic and other times like a police state. The components of the banana industry's power would changeâthe way land and workers were usedâbut those alterations came mostly as tactical responses to maintain the status quo. (Even today, bananas remain Honduras's largest industry, with Chiquita and Dole accounting for nearly 100 percent of the fruit that leaves the loading docks on the country's northeast edge each day.)

In retrospect, the first years following the 1956 coup seem almost like a golden age. The ruling junta allowed elections: The winner was Ramón Villeda Morales. Villeda Morales had also won the 1954 vote, but he'd been denied office, partly because he'd been seen as too left wing. The Honduran was far less radical than his Guatemalan counterpart, but like Arbenz, Villeda Moralesâwho'd worked as a rural doctor before going into politicsâunderstood the injustices that Honduran peasants had been subjected to for decades. And like the failed Guatemalan, the new Honduran president understood that the key to change was land reform.

THE HONDURAN PROGRAM

was strategically modest compared to what Guatemala had attempted. Small plantations and communities were allowed to form rural cooperatives and labor laws were reformed to allow social security and increased protection for workers. The softer approach didn't result in an immediate disaster, but, by 1963, when it appeared Villeda Morales would be reelected by a large margin, and anticipating even more sweeping reforms, the country's military stepped in again: Elections were canceled, Villeda Morales was exiled, and Colonel Oswaldo López Arellano took power. Many of the earlier land reforms were rolled back, and even the United Statesâwhich was beginning to feel uneasy about intervening for the banana companiesâofficially suspended diplomatic relations with Honduras following the coup. The country's new leader purged perceived leftists, especially those with ties to Cuba's Fidel Castro (this pleased the United States, which restored diplomatic relations, with increased military assistance, a year later).

For those laboring on Honduran plantations, the coup marked the beginning of decades where gains were lost, gained, and lost again. Some unions were banned and others grew. Land was transferred to workers then taken away. The one taboo was strikes: As recently as 1991, the military was killing workers who walked off the job.

Where were the banana companies? They were still exerting influence, though more often by stealth than through armed force. And they were still hungry for land, still determined to do things their way, opposing every attempt to provide workers with basic benefits. In 1972 a new form of Sigatoka hit Honduras. In a foretelling of today's Panama disease crisis, the new version of the old malady was more virulent. The related diseases are distinguished by the color they turn banana leaves: yellow for the older malady and black for the modern version.

To combat Black Sigatoka, which remains the most widespread banana disease in the world, aerial spraying of the crop was increased, resulting in further damage to the health of workers on the ground. United Fruit needed to gain market share in order to cover the increased expense of fighting the new disease, so it embarked on a price war with Fyffes (the former subsidiary) that ultimately led to the British rival's departure from the country, along with accusations that Chiquita had hired agents to destroy competing banana shipments. In other words, though the actors, techniques, and storyline shifted constantly, Honduras remained the quintessential banana republic.

ELI BLACK WANTED TO CHANGE THAT

.

Looking at his balance sheets, the entrepreneur who'd made his fortune as a Wall Street takeover king seemed an unlikely reformer. Like Sam Zemurray, Black was a Jewish immigrant who'd arrived in the United States poor, and with a different name, coming from Poland in the mid-1920s as Elihu Menashe Blachowitz. (Black only changed his name as an adult, after he'd entered Columbia Business School.) Black was as ambitious as Zemurray, as well. At age thirty-two, after a successful stint as an investment banker, Black picked a long-shot, troubled companyâAmerican Seal-Kap, which manufactured paper cups and drinking strawsâand restored it to health; he flipped the profits into a takeover of a meat-packing concern.

Black's next target was United Fruit. The late 1960s were a time when many small U.S. companies merged into huge conglomerates. In 1967 pineapple importer Castle & Cooke bought Standard Fruit, eventually leading to the use of its Dole brand name for its bananas (sales of the traditionally Hawaiian fruit are now dwarfed by bananas, which are Dole's largest product). Today's third-largest banana importer, Del Monte, which was then a maker of canned fruits and vegetables, entered the business by purchasing the West Indies Fruit Company, which mostly operated in the Caribbean. Over the next two years, United Fruit would become the target of a heated takeover battle. Black's rival was a company called Zapata, which had begun in Texas oil exploration. The owner was the first President George Bush. (Once again, we enter the banana labyrinth: Bush's company was formed in 1953; some of its drilling was on islands on the Gulf of Mexico. These islands were allegedly used as staging areas for U.S.-backed activities against Fidel Castro's Cuba, starting in the late 1950s and continuing through the early 1960s. One of those actions was code-named Operation Zapata. Though the Bush connection has never been confirmed, when the planned operation did go through, two of the boats reportedly used were named

Barbara

(Bush's wife) and

Houston

, the future president's adopted hometown. Some of the other vessels used in the failed 1961 operation, which became known as the Bay of Pigs invasion after the public learned about it, were owned by United Fruit, on loan from the Great White Fleet. The banana giant's motive, allegedly, was anger over Castro's takeover of the island's banana plantations.)

Black won the battle for the banana giant with spectacular fireworks: On September 25, 1969, he bought 733,000 shares of United Fruit in a single dayâat the time, the third-largest deal in the history of the New York Stock Exchange. A year later, a weakened United Fruit merged entirely with Black's company; the company that was originally named as a result of the merger between Andrew Preston's import concern and Minor Keith's railroad network was rechristened United Brands.

Black was known as a take-no-prisoners businessman, and his battle with Zapata proved that. But Black was also deeply religious, coming from a long line of Hebrew scholars. Prior to entering the world of finance, he spent three years as a rabbi. Even during his career as a corporate raider, much of the money he earned went to support Jewish philanthropies. He was a member of six different temples and usually spent Saturdays discussing religion with his closest friend, Rabbi Jonathan Levine. It was that background that led Black to feel deeply disturbed about the reputation of the banana company he'd taken over, which he'd almost certainly known about prior to his effort. Changing the company might even have been one of Black's motivations in buying the banana giant: An article in

Newsweek

described the executive as “determined to end United Brands' image as a Yankee exploiter of poor people.”

Yet, before he could transform United Brands' personality, Black first had to address a more practical matterâprofits. In 1971 the company lost $2 million. Black cut budgets, but the next year, the loss was ten times greater. A Federal antitrust suit forced the company to sell more of its Guatemalan holdings, accounting for about 9 million bunches annually, to Del Monte. Deeply in debt, Black sold additional land in Costa Rica. (The sales set the stage for the structure of the banana industry today, with few plantations actually owned by the fruit companies. Instead, the facilities are owned by local interests, who sell bananas to Chiquita, Dole, and other banana exporters under contract. This has allowed the big banana conglomerates to pick and choose suppliers multinationally, based on who offers the lowest price for their fruit. The arrangement is a softened version of the squeeze technique United Fruit used earlier to pressure client countries that threatened to institute land and labor reforms.)

The next years saw mixed resultsâand Black under increasing pressure. United Brands earned praise for its efforts in helping Nicaragua recover from a devastating 1972 earthquake; company money was largely responsible for rebuilding the country's capital, Managua. The same year, the spread of Sigatoka increased across the region. The company's response was to use more, and increasingly toxic, chemical sprays. The health of banana workers declined again. The company was profitable in 1973, earning $16 million, but it also suffered an unthinkable embarrassment: It was overtaken by Dole as the number one banana seller in the United States. Even so, Black announced that the company's assets were finally in order and that the following year would see a return to big profits and market leadership.

But 1974 turned out to be a tragic year for Eli Black and United Brands, whose products now included not just bananas but also sausages and sunglasses. For the first time, Central American governments banded together, announcingâin Costa Rica, Panama, and Hondurasâa dollar-per-box tax on exported fruit. During the summer, Panamanian banana workers went on strike, leading to the formation of the Organization of Banana Exporting Countries, modeled after OPEC, the Middle Eastern oil-producing alliance that had successfully used a boycott and market pressures to raise gas pricesâand precipitate an energy crisisâin the United States the year before. The move hurt the banana company, but were ultimately ineffective because Ecuador, now the world's largest banana-producing nation, refused to join. Nature also seemed to be against the Central American alliance. A day after the organization was founded, a hurricane hit Honduras, destroying three-fourths of that country's banana crop. Once again, Black put company assets into rebuilding Honduras. By the end of the year, the company was on the way to losses nearly three times 1972's record. Black was forced to sell one of the company's few profitable divisions, the Foster Grant eyewear company.

Eli Black was a quiet, almost somber person, not given to revealing his feelings (a former teacher described Black to the

New York Times

as “a boy who always smiledâbut never laughed”). Black also hated defeat. Yet the sixteen-hour days he'd been putting in at United Brands' New York headquarters had failed to yield success; instead, they created grumblings on the part of company executives, shareholders, and banks that Black was better as a dealmaker than a day-to-day manager.

On Saturday, February 1, 1975, Black began a typical weekend with his son. The two visited the barber and watched a movie. The next day, Black had Sunday brunch with his family in his Westport, Connecticut, home. Black then drove into Manhattan, where he spent the night at his Park Avenue apartment. Early Monday morning, Black was picked up by his chauffeur-driven company car. It took a little more than five minutes for the executive to arrive at his office, in the Pan Am Building, the fifty-eight-story office tower that rises above Grand Central Station (today, known as the MetLife Building). Black took the elevator to his small office on the forty-fourth floor, arriving there just before 8:00 a.m. The entrepreneur stepped inside, closed the door, and opened the window blinds. He lifted his heavy briefcase. “Then,” wrote the

New York Times

, “the man who never raised his voice swung his attaché case against a quarter-inch thick piece of glass.” The window shattered. One final detail: Black meticulously picked up the shards that remained in the window, as if he were neatening the opening he created.