Banana (15 page)

Authors: Dan Koeppel

27

Chronic Injury

T

HE DAMAGE UNITED FRUIT

had done to Latin America was beyond imaginable and, even as the Cavendish shift occurred, beyond healing. The dictatorial governments the company installed in Guatemala and Honduras ruled their respective countries for decades, releasing wave after wave of abuse, assassination, and even genocide. In Guatemala, death squads sponsored by the successors to banana-installed governments roamed the countryside, killing anyone suspected of beingâor even becomingâa left-wing sympathizer. That meant just about anyone who labored on a banana plantation, and their families. It was the obscene, logical extension to the sentiment that had crushed Jacobo Arbenz and his efforts to bring justice to the country's banana lands. Over 100,000 native Mayas died at the hands of the Guatemalan military; tens of thousands more fled the country (most now live in the United States).

Jacobo Arbenz never recovered from his defeat. In his years of exile, he'd become a stateless vagabond. Half-naked and humiliated, he'd first flown to Mexico City, where the leader he'd deposed, Jorge Ubico, was also exiled. Mexico was a U.S. ally, and Arbenzâalong with his wife and daughterâwas soon asked to leave. Arbenz's father was Swiss, and that country was the next to shelter him, but said that he could stay only if he renounced his Guatemalan citizenship. Arbenz refused to deny his allegiance to the country he'd worked to free.

Eastern Europe seemed promising, but the only country that would take him was Czechoslovakia. Even though it was behind the iron curtain, Prague felt cosmopolitan, accessible. But the government there was unable to provide Arbenz with housing or the money he needed to take care of his family; unlike other fleeing dictators, the Guatemalan had not escaped with briefcases or foreign bank accounts filled with looted cash. There seemed to be just one place left to go: the Soviet Union, the country he'd been accused of conspiring with. His arrival in Moscow confirmed, for much of the world, that the U.S. action in Guatemala had been correct. But Soviet officials were less than welcoming. They refused to allow Arbenz to see his family.

What Arbenz really wanted was to go homeâor at least to get closer. His native country was out of the question, but as time passed, he believed some other Latin American nation might agree to host him. The conditions offered by Uruguay were less than attractiveâhe couldn't hold a job or speak out politically, and was required to report in to the national police weeklyâbut it was the only offer he received. It was three years after the coup. Nothing was going right. His daughter, Arabella, became moody and depressed. His wife, Maria Cristina Vilanovaâwho was so passionately committed to the reforms her husband had advocated that she'd allowed her family's own estate to be returned to the peasantsâfelt helpless and tired.

In 1960, finally, there was hope. Revolution in Cuba had brought Fidel Castro to power. Though Arbenz's decision would again be seen as confirmation of his Communist leanings, and he knew there was a huge difference between himself and the dictator, Arbenz accepted Castro's offer of permanent, unrestricted asylum.

Finally, Arbenz might have peace, if not happiness.

Arabella, just fifteen years old, refused to go. She protested when her parents tried to send her to what she saw as elitist private schools but also refused to join any Communist youth groups. As her mother and father settled in Cuba, she left for Paris, proclaiming that she'd become an actress.

Arbenz still dreamed of returning to Guatemala. He'd promised, in his last radio address, that “obscured forces which today oppress the backward and colonial world will be defeated.” Instead, his defeat was made complete. His daughter was far away, figuratively lost. Soon, she'd be gone entirely. She'd fallen in love with Jaime Bravo, who was, at the timeâ1965âpossibly the world's most famous matador. Bravo was also a notorious playboy, and as the two argued in a Bolivian hotel room, Arabella turned a gun (where it came from was never fully determined) on herself.

Arabella's loss dwarfed Arbenz's defeat in Guatemala. The drinking habit he'd fallen into during the last days of his regime turned stag gering during his time in Cuba. Was he still Jacobo Arbenz, the symbol of freedom? Or was he an object of disdain, representing weakness, as Fidel Castro implied when, with the exiled president watching on, he vowed that his country had learned a lesson: “Cuba,” he said, “is not Guatemala.”

Arbenz knew what had happened to him, but he never understood why. He'd only wanted land the banana companies weren't using. Why had they objected so violently? He'd been willing to negotiate. What he didn't know was how badly the desperate fruit company believed it needed that land. He didn't know that every square foot of fallow plantation was being held, just in case a cure was found for a rampaging disease. Panicked by an opponent that was out of its control, United Fruit wouldn't budge and unleashed terrible vengeance on anyone who tried to force it to yield.

BUT ARBENZ WASN'T AWARE OF THIS

.

In 1971, he returned to Mexico City. By then, almost thirty years after he'd been deposed, he had fallen into obscurity. If he was thinking of lost opportunities or of new strategies or of the civil war that was killing tens of thousands of his countrymen back home, there's no record of it. There are those who believe that his last moments were filled with terror, at intruders who were looming over him as he lay in a hotel bathtub with a bottle of whiskey by his side. Maybe, at that moment, he was thinking of Arabella.

Arbenz sank into the water. The man who dared to mount the boldest action ever attempted against the big banana company, before or since, wouldn't open his eyes again.

IN OCTOBER 1995

,

Jacobo Arbenz finally returned to Guatemala. One hundred thousand onlookers wept as the former president's body was drawn down Guatemala City's main avenue in a grandly decorated funeral carriage. The martyred ruler was interred in a white, pyramid-shaped mausoleum that is still visited by pilgrims today. Arbenz, to many Guatemalans, is their country's Lincoln or Kennedy. Carlos Castillo Armas, the man who deposed him, is buried just a few feet away, under a largely ignored gray headstone.

For years a debate raged in the United States over whether Arbenz was in fact a Communist, how much United Fruit was involved in the coup, and whether the entire operation had actually been stage-managed by the CIA. Starting in the late 1970s, Freedom of Information Act requests revealed thousands of pages of U.S. government papers, including budgets for the operation, and cables and correspondence between officials in Washington, intelligence operatives, United Fruit executives, and conspirators in Central America. One document lists over fifty Guatemalan officials targeted for “elimination.” A second contains instructions on how to accomplish that goal, in handbook form. The nineteen-page manual, reprinted in

Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of Its Operations in Guatemala, 1952â1954

, by Nick Cullather, is titled

Study of Assassination

. “The simplest local tools are often the most efficient means of assassination,” counsels the booklet. “A hammer, axe, wrench, screw driver, fire poker, kitchen knife, lamp stand, or anything hard, heavy and handy will suffice.” The authors do note that murder is not ethically justifiable, and that “persons who are morally squeamish should not attempt it.” (I find it almost too grotesque to attempt to contemplate any good reason why a government founded on principles of freedom and democracy could so casually dismiss any debate between right and wrong, especially just nine years after the end of World War II.)

Even as they adopted the Cavendish, and their need for territory diminished, the banana companies didn't change all at onceâor even change completely. Political adventures continued, though they'd center around more conventional bribery, graft, and union busting. But for the most part, the banana with stickers became an uncontroversial and beloved consumer product and one the larger world wanted. The fruit gained popularity in Europe and Asia. It was the unique wonder of the Cavendishâportability, convenience, strength, and most of all, consistencyâthat would make it so ubiquitous. These are, of course, the same things that make it so sick today.

28

Banana Plus Banana

B

ANANAS,

wrote Australian biotechnology researcher James Dale, are a “plant breeder's nightmare.” No seeds means no fertility. Multiple diseases mean that breeding for only a single kind of resistance can yield a new fruit that is promising yet functionally useless if it is still susceptible to another malady. Even if a new banana can fight off most of the organisms that attack it, it still has to meet the other requirementsâshipping, ripening, and tasteâthat make it something more than a locals-only product. Thousands of agricultural expertsâscientists and hobbyists, small-scale farmers and huge agribusinessesâspend years developing new species of roses, apples, melons, and citrus fruits. Bananas? Too difficult. Emile Frison, former director of the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain (INIBAP), estimated that the total number of scientists attempting to grow new bananas in the field was less than the number of fingers on a typical bunch of the fruit they were working on: just five.

To successfully breed bananas, you have to be stubborn; prideful; and, perhaps to the point of danger, obsessedâqualities that carry on, in an academic form, the tradition of the most celebrated and infamous

bananeros

. That was the case with the first scientists who attempted to make modified bananas in the 1920s, and it remains the case today. Most of all, you have to be patient. From the time the Cavendish was adopted until the first sign of the resurgent Panama disease that now threatens to destroy it, the person who best embodied those traits was Phil Rowe.

Rowe didn't invent the painstaking techniques that allowed banana scientists to breed the unbreedable, but he sharpened them, perfected them, and even succeeded with them, through a combination of genius and determination. Rowe arrived in Honduras in 1959, immediately after graduating from college. It was, according to retired Chiquita banana breeder Ivan Buddenhagen, the beginning of “the second flowering of banana research.” (The first was the research centered around the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture in Trinidad, during the 1920s and 1930s, which yielded the first hybrid fruit but failed to find an acceptable replacement for Gros Michel. It also established the fundamental methods banana scientists still use to create new versions of the fruit.)

There were reasons for United Fruit to improve the banana, even after the Cavendish was adopted. Though it wasn't seen as urgent, or even necessary, at the time, to find an alternative to the world's new banana, United Fruit did hope to develop a variety that would be better than the one offered by Standard Fruit and other competitors.

Rowe's lab was in La Lima, at the huge company compound where a community of American employees oversaw the thousands of Honduran workers who grew bananas across most of the country's eastern lowlands. Over the next few decades, the facility would house the world's most successful banana-breeding program (and one that remains in operation today).

The first step in breeding bananas has always been to have good raw material. Because bananas are sterile and generally seedless (the Cavendish is absolutely seedless, which is why it cannot be bred by any conventional method), that means bananas of a kind that

can

be bred. Rowe began with a huge collection of wild and rare bananas gathered by O. A. Reinking, a legendary explorer of tropical fauna, who traveled through Indochina and the Malay Peninsula then island-hopped from the Philippines through Java, Bali, and New Guinea and all the way to Australia between 1921 and 1927. Reinking was one of the early contributors to a greater understanding of Panama disease, helping to pin down the structure of the fungus in 1933. His sample of fusarium, collected in the Philippines, is now housed in the U.S. National Fungus Collections of the Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Research Service (yes, there is such a place).

Reinking returned home with 134 different banana types: 81 that propagated nonsexually, the way cultivated bananas do; 26 that were clones of traditional plantains; and 27 wild, seeded bananas. The collection was initially housed at United Fruit's Panama research labs, not in test tubes and petri dishes like today's preserved bananas, but as living fruit grown in greenhouses. But the company's half-hearted commitment to banana science, motivated by poor results and the land-grab alternative, led to the quick abandonment of the program. In 1930 the entire Reinking collection was moved to Wilson Popenoe's Lancetilla gardens. (Reinking also collected citrus and spent much of his early career attempting to prove the existence of the Rumphius pummelo, initially described in the eighteenth century, which most experts considered to be mythical. He finally found the fruit, which is like a grapefruit with a second grapefruit growing inside, on the Banda Islands in Indonesia.)

The Reinking bananas were mostly forgotten until the mid-1950s, when United Fruit belatedly, and half-heartedly, began searching for a replacement for the Gros Michel. Seventy-two of the samples were then transferred to La Lima, where Rowe was opening his research facility, forming the beginnings of a collection that is still the basis for most Honduran testing today.

A banana breeder needs that kind of variety. It isn't hard to find seeds in a wild banana: When the fruitsâwhich are generally shaped like the bananas we eat, though sometimes less curvedâare cut in cross section, they reveal as many as two dozen pea-sized, black pits. The seeds are the raw material, and researchers will usually set aside a separate section in a plantation to grow the fertile fruit. They'll then be exposed to the same maladies that threaten bananas people eat. Those with desirable strengths are then grown in quantity. Visitors to an experimental plantation will see rows and rows of them, each marked with a species name and planting date.

The serious manual labor begins in these rows. Since few of the experimental plants exhibit the necessary combination of traits from the start, they're often bred with each other. In four decades of research, Rowe and his colleagues created nearly twenty thousand hybrids, or about four hundred times the number of edible varieties that emerged over seven thousand years of conventional human cultivation.

Breeding such a banana is the agricultural version of an arranged marriage. At dawn, workers head into the fields, sometimes on bicycles, wearing utility belts that hold a dozen or more collecting containers (they resemble, appropriately, baby-food jars). They climb up ladders to gently scrape finely powdered pollen out of the nine-month-old male portion of the hermaphroditic plant's flowers, which hangs upside-down at the top end of the bloom, and brush it into the jars. Later that morning, the collected pollen is placed into the stigma, the passageway to the plant's ovary. (In nature this is done by insects, which aren't choosy enough to conduct decent banana-breeding experiments.) Four months later, the new plant is harvested.

At the Fundacion Hondureña de Investigación Agricola, or Honduran Agricultural Research Foundation (FHIA), La Lima's publicly funded successor to Phil Rowe's United Fruit research station (and the first place I visited when researching this book), Juan Fernando Aguilar, the facility's current director, led me through the fields as we followed the bike-riding pollenators.

This is an experimental plantation, where the fruit grows unprotected, undefended. There is no aerial spraying, no careful bagging to keep fruit unblemished and healthy. Instead, the test plantation invites all comers: beetles, bugs, and burrowing worms; viruses, fungi, and bacteria. The field is a ragtag layout with fruit of different sizes and colors, trees of varying heights, and plants with vastly contrasting levels of healthiness.

We walked over to a large work area, shaded by a tinted, corrugated plastic roof.

“We harvest about one thousand bunches each week,” Aguilar told me, as he lit a cigarette and stared down at his white shirt, which was clean when we'd met earlier that day but now had a huge blot of banana sapâunremovable and rubbery, the dark tops of the bananas we peel are made of the same substanceâsplattered on it. “That's the true banana researcher's logo,” he shrugged.

The harvested bananas are first arranged by “cross” (the two parent types) and then by the desired attribute the breeders are hoping for. (So, if a hypothetical Lucy banana is bred with an equally fanciful Ricky fruit, all are put together into one section. They are then further separated according to the various goals of the hybridization: thick skin, resistance to disease, or a specific taste. Generally, a new banana is bred with one attribute in mind; it is then merged with a separate man-made fruit that possesses one of the other desired qualities. The results are then crossed and crossed again until, in theory, the banana that has everything emerges.) Next, the fruit is stored in a ripening room for several daysâthe room contains a precise mixture of ethylene and carbon dioxide gassesâand then taken into a larger work area to be peeled.

Ordinarily, the only thing a person peeling a banana needs to worry about is where the peel goes. Avoiding a slapstick tumble is not the issue in banana breeding. Instead, the primary objective is finesse. Every single banana from the week's harvestâthat can be up to

100,000

bananasâis carefully skinned then segregated (sometimes in separate containers, other times by working on different types at different times) so that one breed doesn't mix with another. The peeling at FHIA is done by women, paid ten dollars a day, about double the typical Honduran wage. Aguilar says they are better at precision work than men. “They handle the fruit more gently,” he told me. “And they have better handwriting.” Each separate bunch has to be identified and logged, so that its success or failure can be tracked through the entire growing cycle. (The peels are usually composted and fed to pigs.)

The men return in the next step. The logged bunches are transferred to their own barrels, where they're fermented. (The process produces a vinegary smell that's partially sweet, partially overripe. The aroma is a bit sickeningâand very much like that of Ugandan banana wine.) The now-oozing bananas are lifted by workers in protective gearâsmocks and rubber bootsâand poured into an oversized sieve, where they're crushed into a pulp by a heavy, steel mallet with an eight-foot-long handle. The smashing has two primary byproducts: the impossible-to-clean stickum and a gooey banana concentrate. The adhesive waste is discarded, while the fruity muck is transferred to smaller mesh seivesâeach about the size of a sheet of standard typing paperâwhere women carefully wash the mixture. The goal is to find a tiny speck of fertility amidst tons of traditional banana barrenness. Aguilar showed me a table with a container that held about two dozen seeds. Since, for the most part, seeded bananas are being crossed with seedless ones, and since seediness is one of the attributes being bred

out

of the bananas, the seed yield is maddeningly low. “Those seeds there,” Aguilar said, “came from about a quarter million bananas.” That makes the odds of finding a seed ten thousand to one.

That was the end of the process for the banana breeders up until the 1970s. They'd replant the found seeds, crossing and crossing again until, with luck, a viable commercial fruit was developed. Though a few bred bananas made it to larger plantations, for the most part, the first four decades of banana breeding yielded a success rate of approximatelyâ¦zero.

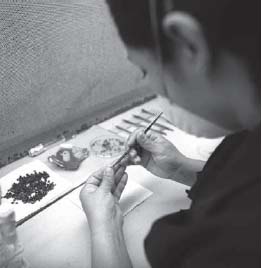

Building a banana: the men pollinateâ¦

â¦and the women handle the delicate seeds.

Rowe helped develop an additional step called “embryo rescue.”

In this case, the seed is not the end of the human-assisted banana reproductive process. Every viable seed, when cut open, contains a tiny embryo about one-fiftieth the size of the seed itself. In Honduras I watched as technicians, using Rowe's technique, peered into microscopes and carefully removed the embryos, dropping them into test tubes containing a fertilized growing medium.