Basic Principles of Classical Ballet (9 page)

Read Basic Principles of Classical Ballet Online

Authors: Agrippina Vaganova

If at the beginning of an exercise the thumb is not pressed firmly on the third finger, all the fingers will become spread out, because the attention during the exercise will be transferred to the legs and the body. This grouping of the fingers may be modified as the pupil progresses.

First Position. The arms are raised in front of the body on a level with the diaphragm. They should be slightly bent, so that when they open into the 2nd position, they unbend and open to their full length. On raising the arm to the 1st position, it is held up from the shoulder to the elbow by the tension of the muscles in the upper part of the arm.

Second Position. The arms are opened at the side, very slightly rounded in the elbow. The elbow should be well held up by the same tension of the muscles of the upper part of the arm. The shoulders should not be drawn back or raised. The lower part of the arm, from the elbow to the wrist, is held on a level with the elbow. The hand, which due to this tension falls and appears to be hanging, should also be held up, so that it, too, takes part in the movement.

By holding up the arms in this position during the lesson, we develop them in the best manner for the dance. At the beginning the arm will look artificial; the actual result, however, will come later. The elbow will never drop, the arm will require no attention, it will be light, sensitive to every position of the body, alive, natural and highly expressive. In short, it will be fully developed.

Third Position. The arms are raised over the head, the elbows rounded; the palms are inward, close to each other but not touching. The dancer should be able to see them without raising her head.

The movement of lowering the arms from the 3rd position through the 2nd into the preparatory position should be done very simply: the arm will come into the correct position by itself upon reaching its final point.

The incorrect manner of some teachers who introduce an excessively sweet plasticity should be avoided. In bringing the arm into the 2nd position, they draw it slightly back and turn the hand palm downward. This breaks the line. The movement appears to be broken, unnecessarily complicated and sweetened.

I repeat, the hand will turn naturally when it is necessary. This artificial turn of the hand is a typical movement of dancers who call themselves plastic dancers

18

Their meagre technique needs such adornments, because otherwise they will have nothing on which to build their “dances”. We, in our school, do not need it.

Arabesques require a special position of the arms. The arm is extended in front, the hand placed palm downward. The elbow should not be extended too tightly, and the shoulder should not be pushed forward.

The French manner of bending the wrist upward obscures the expression of the whole figure and puts the accent on the arms; the audience looks at the arms and not at the general line. My manner is closer to the Italian, but the movement is freer, the fingers lie unrestrained, the hand is not so much stretched out.

PORT DE BRAS

Port de bras is the foundation of the great science of the use of arms in classical ballet. The arms, legs and body are developed separately through special exercises. But only the ability to find the proper position for her arms lends a finesse to the artistic expression of the dancer, and renders full harmony to her dance. The head gives it the finishing touch, adds beauty to the entire design. The look, the glance, the eyes, crown it all. The turn of the head, the direction of the eyes, play decisive roles in the expression of every arabesque, attitude—in fact, of all other poses.

Port de bras is the most difficult part of the dance, requiring the greatest amount of work and concentration. Perfect control over the arms is an immediate indication of a good school.

This is particularly difficult for those who are not naturally endowed with beautiful arms. They, more than anyone else, must watch their arms. Through a well-thought-out use of them, they can acquire beauty of line and movement. I have had pupils with naturally exquisite arms, who, through lack of knowledge of port de bras, had no freedom of movement. Only upon mastering port de bras did they begin to manage their arms.

It is necessary that the arms, from the preparatory position, be rounded so that the point of the elbow is not seen; otherwise the elbows will form angles which destroy the soft outline the arms must have. The hand must be on a level with the curve at the elbow; it must be held up and not be bent too much, otherwise the line will be broken.

At the present time there is a tendency toward undue stretching of the hands which gives a harsh, stiff line. The elbows must be held up and the fingers held in the indicated grouping. The thumb should not be stretched out.

Shoulders must be held down and left immobile. The positions of the arms and port de bras must seem spontaneous. Each movement of the arms (poses) must pass through 1st position. This principle must be applied both to dances on the floor and movements in the air.

As soon as one begins to study port de bras the execution of steps takes on a more artistic, polished appearance. The arm begins to “play”.

If we do not require anything more of the hand than a correct position in relation to the entire arm, while the whole attention is centred on the development of the legs, the harm is not so great. Besides, to teach the arm to remain still, to be free and independent of the movement of the legs, is a very important stage in the development of a dancer.

With children and beginners the arms always attempt to imitate the movements of the legs, to share in the work; for instance, when doing a rond de jambe, the arm unconsciously describes a vague circle. But when the pupil manages to dissociate the movements of the arms and legs; when, with concentrated work of the legs, with sometimes terrific effort to achieve the desired movement, the pupil manages to leave the arm quiet, not participating in the movement—that already is a step forward.

Besides, in order to develop the arm, to bring it into an obedient and harmonious state, one needs infinitely less time than to develop the legs within the limits required for the classical dancer. The leg develops, strengthens, is disciplined by long continuous daily work. No matter how little time is left for the arms in comparison with the legs, they will get their necessary workout.

One recalls those plastic dancers who in several months develop quite bearable arms, while one cannot help but say that their bodies and legs are still in the most primitive condition.

Therefore when doing exercises designed to develop the legs, the hand may remain still, so long as it is held correctly. With port de bras the hand comes into play and gives the exercise its full colouring.

Here, too, begins the training for control of the head and its correct direction, as it is the head that determines every shading of movement. In port de bras the head participates all the time.

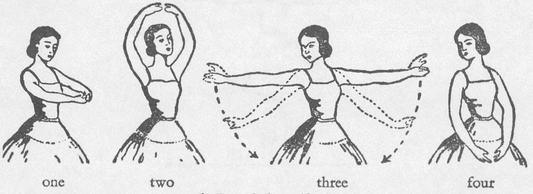

26. Port de bras (first)

Ports de bras are numerous and varied. There are no special names for the different forms. I shall cite several examples.

1. Stand in 5th position croisé, right foot in front. From the preparatory position the arms go into 1st position, are raised to 3rd position, open in 2nd position, and are lowered to their starting-point in the preparatory position.

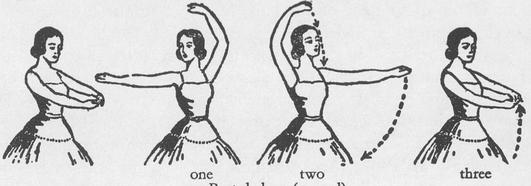

27. Port de bras (second)

In order to lend this exercise the character it requires, in order, as we say in class, to “intake a breath with the arms” they must be used as follows:

When the arms arrive in 2nd position, open the hands, taking a deep, quiet, but not exaggerated breath (without lifting the shoulders!), turn the hands palms down, and as you exhale, bring them smoothly down, allowing the fingers to “trail” slightly behind, but without overemphasizing, and without too much break at the wrist.

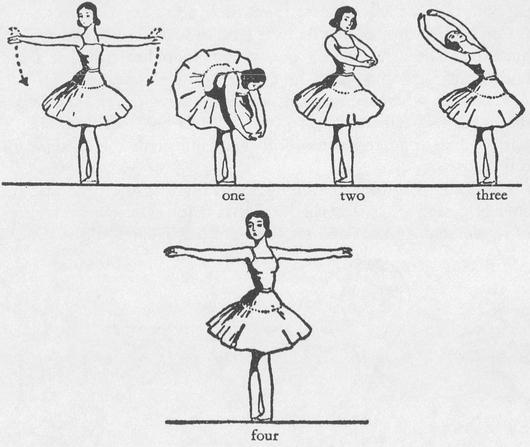

28. Port de bras (third)

The head bends to the left when the arms reach 1st position, the glance follows the hands; when the arms are in 3rd position, the head is straight; when the arms open, the head turns and inclines to the right. At all times the glance follows the hands. When the movement is finished, the head is straight once more.

2. Stand in 5th position croisé, right foot front. From the preparatory position the arms go to 1st position, then the left arm goes to 3rd, right arm to 2nd, then left arm to 2nd, right arm to 3rd. Then left arm is lowered to preparatory position, passes it and comes up to 1st, where it meets the descending right arm. From here the entire movement is repeated.

The head accompanies the movement in the following manner:

When the arms are in 1st, glance at the hands inclining the head to the left; in the next position the head turns to the right; when the right arm is in 3rd position, the head inclines and turns to the left. At the conclusion of the movement the head is turned to the left.

3. Stand in 5th position croisé. Opening the arms into 2nd position (head to the right), “breathe” with them, as described in the first port de bras, and lower them into preparatory position, simultaneously bending the body and the head forward and keeping a straight spine all the time. Then begins the unbending which is done in the following manner: first, the body straightens out, i.e. rises to the initial position, during which the head and body are raised simultaneously with the arms; the arms move through 1st position into 3rd, then the body bends back as much as possible, but the head should not be thrown back, and the arms, according to the accepted rules, should be in front of the head and should not escape the eyes which are fixed on them; the body unbends, the whole figure straightens out, the arms open into 2nd position.

This port de bras may be done to a 4 beat rhythm: on

one—

bend the body forward, on

two

—straighten to initial position, on

three

—bend back, on

four

—return to initial position and open arms into 2nd position.

4. The following exercise belongs to the Italian school, but is now widely in use with us, and is applied to every exercise. However, in order to give it that stamp of artistic finish which is inherent in it (in spite of its seeming simplicity of form) great care must be exercised in its proper execution. I shall endeavour to explain it in detail, although it is difficult to express in words the free, smooth flow of its interlacing parts.

Stand in 5th position croisé, right foot front. The arms go through 1st position, the left into 3rd, the right into 2nd position. Open the left arm into 2nd position, at the same time vigorously expanding the chest, tensing the back and arching the spine, bring left shoulder so far back as to see it well from the back in the mirror, and as you are thus turned to the left, the right shoulder will be in front. The head is turned to the right. In spite of the powerful turn of the body, the feet do not move. Then the right arm is moved into 1st position, where the left arm, rising from below, meets it. The body returns to starting position.

Now, the last of all details. When one arm is in 3rd, the other in 2nd position, the hands follow palms down, fingers extended as if cutting the air and meeting with some resistance, so that the wrist is slightly bent, hands trailing after arms.