Basic Principles of Classical Ballet (5 page)

Read Basic Principles of Classical Ballet Online

Authors: Agrippina Vaganova

5. Demi-plié in 4th position and full plié in 5th position

Later on, when the pupil learns to use her arms, this plié may be done also with port de bras.

ÉPAULEMENT (HEAD AND SHOULDERS)

Épaulement is the first suggestion of future artistry of classical dancing which is brought into beginners’ and children’s exercises.

The study begins with the movements of the legs. The pupil stands en face, directly facing the teacher, until she gets used to doing the exercises holding the body still. Then some play of the body may be introduced and a hint of future artistic colour added.

En face is the natural direction for the 1st and 2nd positions and generally they remain so. But the 3rd and 4th positions are done with a turn of the shoulder: if the right foot is forward, the right shoulder is turned forward and the head is turned to the right.

The 4th position permits a dual turn. If the position is taken croisé, the right shoulder is forward and the head to the right, if it is taken effacé, the right foot is forward, but the left shoulder is turned forward and the head to the left.

In this manner the basic characteristic of classical ballet is introduced from the very beginning, since classical ballet is built on croisé and effacé. It is from croisé and effacé that the richness of its forms is drawn, and it could never blossom out so luxuriously were it confined to the tedious and monotonous directions en face.

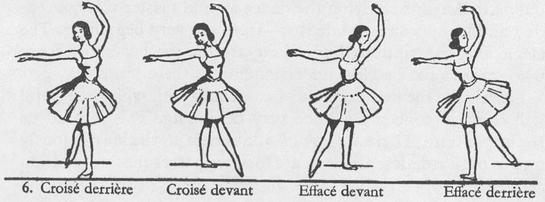

CONCEPTIONS OF CROISÉ AND EFFACÉ

Speaking of épaulement, we arrive at the two basic positions of classical ballet and point out their indispensability for the development of diversity and completeness in the forms of the dance. I shall now discuss the basic types of croisé and effacé.

CROISÉ

The fundamental characteristic of croisé is the crossing of legs. The croisé position can be forward and backward.

Croisé forward: stand on left foot, right leg open forward with the toes pointed, front of body turned toward point 8, head to the right, left arm lifted in 3rd position and the right one taken to the side in 2nd position. This is the basic pose of croisé forward, but the arms and head may be arranged in various ways and combinations.

Suppose you lifted your right arm and took the left one into 2nd position. To finish the design, you may incline your head forward so as to look under your right arm; or lift your eyes toward the left arm, in which case the head must be thrown back a little.

With this variation of the direction of your eyes, the facial expression will change involuntarily. In the previous poses, the inclined head draws together the features of the face; in this pose, the lifted eyes and the thrown-back head smooth the features—the expression becomes more strict and spiritual.

It is very desirable to introduce these changes of facial expression as early as possible, so as not to have later on an expression which is once and for all petrified, or an eternal frozen smile.

Croisé backward: stand on right foot with the same turn of the body and head, left leg extended behind with toes pointed. In the basic pose of croisé forward the arm which was lifted contrasted with the extended leg; here the arm is lifted which corresponds with the extended leg; i.e. left arm lifted, right one to the side, head to the right.

Here, too, the arms and head may be arranged in various combinations. For example, right arm lifted, left one to the side, body slightly forward, head inclined so as to look under right arm. One arm may be lifted upward, the other one bent into 1st position, etc.

EFFACE

In this position, in contrast with croisé, the legs are open.

Effacé forward: stand on left foot, right one open forward with toes pointed, body facing point 2; head to the left, left arm in 3rd position, right arm open in 2nd position, body thrown back.

This is the basic pose. But you may bend the body forward and look under the left arm. There are also other possible combinations; for example, the wrists may be turned outward, etc.

Effacé backward: stand on right foot, left one backward with toes pointed in directions of point 6; the same direction for head, arms and body. But the body is slightly bent forward, and the pose assumes a hint of flight. Other combinations are also possible.

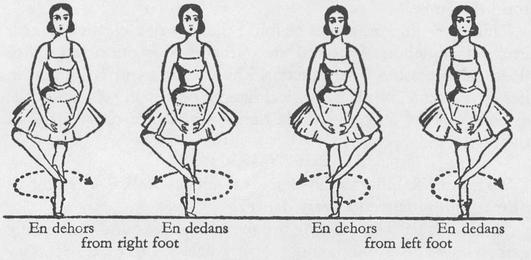

TURNS. EN DEHORS AND EN DEDANS

EN DEHORS

The conception en dehors defines rotary movements directed outward. Anyone studying the dance should master this conception and its opposite—en dedans—from the very beginning. The elementary descriptions I give here are for the benefit of those who want to have a clear understanding of these terms.

Let us take the first example of en dehors with which the pupil will come in contact from the very beginning. This is rond de jambe par terre. There are no difficulties here, as the leg obviously moves outward, describing an arc forward passes the 2nd position and back.

It is much more difficult to understand rond de jambe en l’air en dehors. The beginner is led astray by the fact that the leg extended in the 2nd position moves in the beginning of the movement in a half-circle seemingly inward, going through the rear half of the circle.

I have succeeded in explaining the direction of rond de jambe en l’air to pupils who could not understand it in the following manner.

I ask them mentally to transfer rond de jambe en l’air to the floor. If the leg in all parts of the circle goes in the same direction as in rond de jambe par terre en dehors we have a rond de jambe en l’air en dehors and vice versa. Then the pupil understands easily that en l’air she finishes with an outward movement, while par terre she begins with an outward movement, but in both cases it is the front arc of the circle which is en dehors.

As to en dehors in turns around one’s own vertical axis, the most elementary explanation is the most comprehensive. You turn en dehors when you turn

away

from the leg on which you stand: i.e. if you stand on the left leg and turn to the right, the movement will be en dehors, and vice versa.

EN DEDANS

En dedans defines rotary movements directed inward.

For rond de jambe the explanation is analogous to en dehors, but the directions are changed accordingly. In turns, the movements will be

toward

the leg on which you stand: i.e. if you stand on the left leg the turn is to the left and vice versa.

7. Turns

If these basic conceptions of en dehors and dedans are mastered in the elementary movements, it will be easy to understand them in the more complicated cases, because they will always include the element either of rond de jambe or turns.

The conception en dehors also defines the turned-out position of the leg accepted in classical ballet. People who know nothing about classical ballet tell all sorts of false and nonsensical things about the turn-out. Therefore I shall explain the origin of the turn-out in detail, borrowing some terms from anatomy.

The turn-out is an anatomical necessity for every theatrical dance, which embraces the entire volume of movements conceivable for the legs, and which cannot be accomplished without a turn-out.

The turn-out is the faculty of turning out the knee to a much greater extent than is made possible by nature. The foot turns outward together with the knee; this is a consequence and, to a certain degree, an auxiliary movement. The aim of the turn-out is to turn out the upper part of the leg, the hip-bone. The result of the turn-out is freedom of movement in the hip joint. The leg can be more easily extended and crossed with the other leg.

In the normal position, the movements of the legs are greatly limited by the build of the joint between the pelvis and the hip. As the leg is extended, the hip-neck meets the brim of the acetabulum and further movement is impossible. But if the leg is turned out en dehors, the big trochanter recedes, and the brim of the acetabulum meets the side flat-surface of the hip-neck. This allows the leg to be extended to an angle of 90° and even 135°.

The turn-out enlarges the field of action of the leg to the proportions of the obtuse cone which the leg describes in the grand rond de jambe.

This is the importance of training the legs of a classical dancer in strict en dehors. It is not an aesthetic conception but a professional necessity. The dancer without a turn-out is limited in her movements, while a classical dancer possessing a turn-out is in command of all conceivable richness of dance movements of the legs.

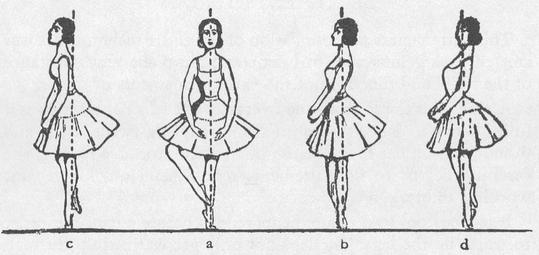

STABILITY—APLOMB

To master stability in the dance, to gain aplomb, is a matter of primary importance to every dancer.

Aplomb is perfected during the years of training and can be fully gained only at the end of study. Nevertheless, I think it necessary to include aplomb in the basic conceptions of classical ballet, because a correctly set body is the foundation of every step.

We begin to master stability at the barre. During the exercises the body must stand straight on the leg, so that the dancer may release the hand which holds the barre at any moment and not lose her balance. This serves as an introduction to the proper performance of the exercises in the centre.

The foot on the floor should not rest on the big toe, but the weight of the body should be distributed equally over the entire surface of the foot. A body which does not stand straight on the foot, but inclines toward the barre, will never gain aplomb and balance. As the work progresses, balance is practiced on the half-toe and on the toe.

8. Position of the body: a, b—correct; c, d—incorrect

When the exercises are done on half-toe in the centre, the proper position of the arms facilitates stability. If the arms do not follow the position which I indicate below, it is very difficult to preserve stability. Only when the dancer has mastered the control of her body to the extent where she can, standing on one leg, hold a single pose for some time, may it be said that she has fully developed her balance and poise.

This definite stability is achieved only when the dancer realizes and feels the colossal part that the back plays in aplomb. The stem of aplomb is the spine. The dancer should learn to feel and control her spine through observation of muscular sensations in the region of the back during various movements.

When you manage to get the feeling of it, and to connect it with the muscles in the regions of the waist, you will be able to perceive this stem of stability.

And then a dancer may undertake freely the most difficult parts of our art, for example, big jumps on one leg, for the performance of which the correct manner of holding the back is indispensable.

II

BATTEMENTS

THE WORD battement in the terminology of ballet means the extension of the leg and its return to the position from which it has been extended. In classical ballet the battement has been moulded into many forms. In describing these forms we shall familiarize ourselves with the substance of this movement.

BATTEMENTS TENDUS