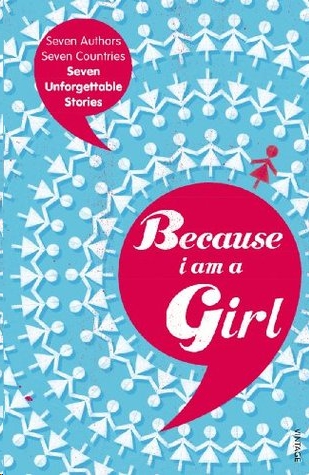

Because I am a Girl

Read Because I am a Girl Online

Authors: Tim Butcher

Contents

Foreword – Marie Staunton, Chief Executive of Plan UK

The Woman Who Carried a Shop on Her Head – Deborah Moggach

Ovarian Roulette – Kathy Lette

Ballad of a Cambodian Man – Xiaolu Guo

A Response – Subhadra Belbase, Country Director of Plan Uganda

About the Book

Seven authors have visited seven different countries and spoken to young women and girls about their lives, struggles and hopes. The result is an extraordinary collection of writings about prejudice, abuse, and neglect, but also about courage, resilience and changing attitudes.

Proceeds from sales of this book will go to

Plan

, one of the world’s largest child-centered community development organisations.

Foreword

MARIE STAUNTON, CHIEF EXECUTIVE OF PLAN UK

‘How do you feel sending these girls out into the street every night, knowing what will happen to them?’ I asked. A pretty stupid question, as my fifteen-year-old daughter commented later. I was visiting a hostel in Alexandria where, during the day, teachers and counsellors supported homeless girls. But while the boys’ hostel is open day and night, the Egyptian authorities do not allow overnight stays in the girls’ hostel. So, at five o’clock every afternoon, girls as young as nine are given a little bag with soap and a first-aid kit, and locked out of the only home they know. In years of working all over the world nothing has affected me quite like that image so, yes, perhaps it was a stupid question.

To survive on the streets, these girls have to join one of the hundreds of gangs in Alexandria, whose joining fee is sexual abuse by older gang members. The authorities

believe

that girls who are not virgins, who are now ‘ladies’ are automatically the responsibility of their non-existent husbands. And this blind presumption means that the girls are officially invisible, leaving them, often with their own babies, at the mercy of all the predators on the street.

This book was compiled to make such girls visible in a way that reports and statistics cannot. Recently Plan published research which showed that in many countries girls as young as ten have sex with their teachers to secure better grades. The research received no coverage in the UK’s media.

How to make these victims visible? I remember travelling to a forgotten famine in remotest Sudan with the journalist Bill Deedes. His subsequent report – a simple story powerfully told – shocked readers and prodded governments into action. I enrolled the help of publishers The Random House Group in order to find writers who were willing to go to the places where girls get a raw deal – where girls are fed less than their brothers; are more likely to be taken out of school; are more likely to be abused – and tell their stories.

Writers see with a different eye than development workers. Some responded with passion. Marie Phillips was appalled that the responsibility for sexual abuse was placed on Ugandan schoolgirls, not their abusers.

Kathy Lette was no less passionate but used her wit to illuminate the lives of girls in Brazil in a hilarious but biting story.

Joanne Harris established a strong rapport with the girls she met. Perhaps because of her career in teaching she has an ability to get alongside young people. She shadowed a day in the life of a young girl named Kadeka. As I was sitting in the middle of a village in Togo peeling pimentos, I heard gusts of laughter followed by the appearance of Joanne bent double under a huge load of firewood, the same amount that Kadeka was carrying with apparent ease.

In contrast, Irvine Welsh avoided engagement during his visit to the Dominican Republic. He sidestepped formal meetings, watched from the outside and asked simple, practical questions: the name of a tree, the meaning of a word. His story was a total surprise, but it met with instant recognition from Plan workers in the Dominican Republic – yes, they said, that’s it. He has got what happens here. How did he do that?

Deborah Moggach is a listener. The story she wrote may be fiction but weaves together the many true stories that she drew out of the girls she met. Sitting under her big hat in the shade, gently questioning them with patience and with charm.

Xiaolu Guo is a filmmaker as well as a writer. She also resisted formal engagement and information that came

from

any sort of official voice. She watched and filmed and found out about the history of the country and its people. She internalised an atmosphere, and her story is true to that.

Tim Butcher approached the assignment as a journalist. Travelling in Liberia and Sierra Leone in the footsteps of Graham Greene, he interviewed girls damaged by war and produced a piece of fiction reflecting the fact that they were still being damaged by peace.

As the authors wrote up their stories, the lives of many girls they had met were rocked by the global financial crisis. The annual report that Plan compiles,

The State of the World’s Girls

, showed that in 2009 the financial upheaval took a heavy toll on families and communities everywhere, and that when money is short it is girls and women who are the most affected. The World Bank estimates that in 2009 alone an additional 50,000 African children will die before their first birthday, and most of those will be girls. The Bank’s Managing Director, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, wrote in her introduction to the 2009 report:

As a young girl growing up in Nigeria poverty is never a theory. Living on under $1.25 a day was a reality … and I clearly remember when I had to carry my younger sister on my back and walk for five miles to save her life from malaria. Looking

back

it was education and a caring and supportive family that opened the door to success for me … Investing in girls is an efficient way of breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty. Educated girls become educated mothers with increased livelihood prospects; they also have a greater propensity than similarly educated males to invest in children’s schooling.

Seventy years of experience, working with nine million children across the world, has shown the charity I am part of, Plan, that investing in girls is crucial to breaking the cycle of poverty. We are launching the Because I am a Girl (BIG) campaign to break the cycle of uneducated mothers giving birth much too young to underweight babies who in turn grow up to be unhealthy and uneducated. As part of the campaign, we are following a group of little girls and their families until 2015. One of those girls is Brenda, whose mother Adina was only thirteen when she gave birth to Brenda, her second child. Brenda is now three, and already it is clear that her young mother is struggling to nurture her family. Brenda is withdrawn and often hungry; she is already at a disadvantage and will find it hard to do well at school, if she gets there in the first place.

The twentieth century is considered by most in the developed world to have brought massive progress in female emancipation, and discrimination against girls in

education

is rarely a major issue, although many may hit their heads against a glass ceiling once they leave school. But poorer parts of the world have not seen even this amount of progress. Today’s girls face new threats – urbanisation means more girls, like those in Alexandria, are living unprotected on the streets; during modern conflicts in countries like Liberia, rape is used as a weapon of war.

President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first female Head of State of Liberia, wrote in the 2008

State of the World’s Girls

report:

Fifty per cent of (Liberia’s) population is under eighteen years old and girls make up more than half of this group. Liberian girls experience gender-based violence by older men in their neighbourhoods and by their teachers on a daily basis … I believe that securing the future for our girls is critical to achieving national development. The popular saying ‘when you educate a man you feed his family but when you educate a woman, you educate a nation’ is profound.

Graca Machel, in her support for our annual report,

The State of the World’s Girls

, said, ‘We can no longer accept that girls should not be valued simply because they are not boys.’ Girls around the world have been told by so many people for such a long time that they are worthless, so of

course

they start to believe this. The BIG campaign aims to reverse the lack of belief and investment in girls. Join us by clicking on

www.becauseiamagirl.org

Thank you to all the writers in this book for enduring tough travel schedules and difficult living-conditions to produce unique and enthralling writing, and to Rachel Cugnoni and Frances Macmillan at Vintage Books for their inspiration and understanding. It is only right to give the last word to a girl:

Someday I will prove that I am no less than my brothers

Rakhi, 17

Marie Staunton, Chief Executive of Plan UK, 2009

Road Song

JOANNE HARRIS

Joanne Harris

is the author of the Whitbread-shortlisted

Chocolat

(made into a major film starring Juliette Binoche),

Blackberry Wine, Five Quarters of the Orange, Coastliners, Holy Fools, Jigs & Reels, Sleep Pale Sister, Gentlemen & Players, The Lollipop Shoes

and, with Fran Warde,

The French Kitchen: A Cookbook

and

The French Market: More Recipes from a French Kitchen

. She lives in Huddersfield, Yorkshire, with her husband and daughter.

THERE ARE SO

many gods here. Rain gods; death gods; river gods; wind gods. Gods of the maize; medicine gods; old gods; new gods brought here from elsewhere and gone native, sinking their roots into the ground, sending out signals and stories and songs wherever the wind will take them.

Such a god is the Great North Road. From Lomé by the Bight of Benin to Dapaong in the far provinces, it runs like a dusty river. Its source, the city of Lomé, with its hot and humid streets; its markets; its gracious boulevards; its beach and the litter of human jetsam that roams along the esplanade, and the shoals of mopeds and bicycles that make up most of its traffic. Unlike the river, even in drought the Great North Road never runs dry. Nor does its burden of legends and songs; of travellers and their stories.

My tale begins right here, outside the town of Sokodé. A large and busy settlement five hours’ drive north of Lomé, ringed with smaller villages like handmaids to the

greater

town. All depend on the road for their existence, although many of these villagers have never been very much further than a few dozen miles to the north or south. Often people walk up the track and sit and watch and wait by the side of the road for whatever flotsam it may bring; traders on cycles; mopeds; trucks; women on their way to the fields to harvest maize or to cut wood.

One of these watchers is Adjo, a girl from nearby Kassena. Sixteen years old; the eldest of five; she likes to sit in the shade of the trees as the road unwinds before her. Her younger brother Marcellin used to watch the sky for vapour-trails, while Jean-Baptiste preferred the trucks, waving madly as they passed, but Adjo just watches the road, ever alert for a sign of life. Over the years she has come to believe that the road is more than just dirt and stones; it has a force, an identity. She also believes that it has a

voice

– sometimes just a distant hiss, sometimes many voices, compelling as a church choir.

And in the mornings at five o’clock, when she gets up to begin her chores, the road is already waiting for her; humming faintly; sheathed in mist. It might almost be asleep; but Adjo knows better. The road is like a crocodile; one eye open even in sleep, ready to snap at anyone foolish enough to drop their guard. Adjo never drops her guard. As she ties her sarong into place; knots it firmly at her hip; ties the

bandeau

across her breasts; slips barefoot across the yard; draws water from the village well; hauls it back to

the

washing hut; as she cuts the firewood and ties it into a bundle, as she carries it home on her head, she listens for the song of the road; she watches its sly, insidious length and the dust that rises with the sun, announcing the presence of visitors.

This morning, the road is almost silent. A few bats circle above a stand of banyan trees; a woman with a bundle of sticks crosses from the other side; something small – a bush-rat, perhaps – rattles through the under-growth. If they were here, Adjo thinks, her brothers would go out hunting today. They would set fire to the dry brush downwind of the village, and wait for the bush-rats to come running out of the burning grass. There’s plenty of meat on a bush-rat – it’s tougher than chicken, but tasty – and then they would sell them by the road, gutted and stretched on a framework of sticks, to folk on their way to the market.

But Adjo’s brothers are long gone, like many of the children. No-one will hunt bush-rat today, or stand by the road at Sokodé, waving at the vehicles. No-one will play

ampé

with her in the yard, or lie on their backs under the trees watching out for vapour-trails.

She drops the cut wood to the ground outside the open kitchen door. Adjo’s home is a compound of mud-brick buildings with a corrugated iron roof around a central yard area. There is a henhouse, a maize store, a row of low benches on which to sit and a cooking pot at the far

end

. Adjo’s mother uses this pot to brew

tchoukoutou

, millet beer, which she sells around the village, or to make soy cheese or maize porridge for sale at the weekly market in Sokodé.

Adjo likes the market. There are so many things to see there. Young men riding mopeds; women riding pillion. Sellers of manioc and fried plantain. Flatbed trucks bearing timber.

Vaudou

men selling spells and charms. Dough-ball stands by the roadside. Pancakes and

foufou

; yams and bananas; mountains of millet and peppers and rice. Fabrics of all colours; sarongs and scarves and

dupattas

. Bead necklaces, bronze earrings; tins of

harissa

; bangles; pottery dishes; bottles and gourds; spices and salt; garlands of chillies; cooking pots; brooms; baskets; plastic buckets; knives; Coca-Cola; engine oil and sandals made from plaited grass.

Most of these things are beyond the means of Adjo and her family. But she likes to watch as she helps her mother prepare maize porridge for sale at their stall, grinding the meal between two stones, then cooking it in a deep pan. And the song of the road is more powerful here; a song of distant places; of traders and travellers, gossip and news, of places whose names she knows only from maps chalked on to a blackboard.

The road has seen Adjo travel to and from markets every day since she could walk. Sometimes she makes her way alone; most often she walks with her mother,

balancing

the maize on her head in a woven basket. Until two years ago, she went to school, and the road saw her walk the other way, dressed in a white blouse and khaki skirt and carrying a parcel of books. In those days its song was different; it sang of mathematics and English and geography; of dictionaries and football matches and music and hope. But since her brothers left home, Adjo no longer walks to school, or wears the khaki uniform. And the song of the road has changed again; now it sings of marriage, and home; and children running in the yard; and of long days spent in the maize fields, and of childish dreams put away for good.

It isn’t as if she

wanted

to leave. She was a promising student. Almost as clever as a boy, and almost as good at football, too – even the Chief has commented, though grudgingly (he does not approve of girls’ football). But with a husband away all year round, and younger children to care for – all three with malaria, and one not even two years old – Adjo’s mother needs help, and although she feels sad for her daughter, she knows that reading-books never fed anyone, or ploughed as much as a square inch of land.

Besides, she thinks, when the boys come home there will be money for everyone; money for clothes, for medicine, for food – in Nigeria, she has heard, people eat chicken every day, and everyone has a radio, a mosquito net, a sewing machine.

This is the song the mother hears. A lullaby of dreams come true, and it sounds to her like Adjale’s voice – Adjale, of the golden smile – and although she misses her boys, she knows that one day they will both come home, bringing the wealth she was promised. It’s hard to send her children away – two young boys, barely into their teens – into a foreign city. But sacrifices must be made, so Adjale has told her. And they will be cared for very well. Each boy will have a bicycle; each boy will have a mobile phone. Such riches seem impossible here in Togo; but in Nigeria, things are different. The houses have tiled floors; a bath; water; electricity. Employers are kind and respectful; they care for the children as if they were their own. Even the girls are given new clothes, jewellery and make-up. Adjale told her all this – Adjale, with the golden voice – when the traffickers first came.

Traffickers

. Such a cruel word. Adjo’s mother prefers to call them

fishers of men

, like Jesus and his disciples. Their river is the Great North Road; and every year, they travel north like fishermen to the spawning grounds. Every year they come away with a plentiful catch of boys and girls, many as young as twelve or thirteen, like Marcellin and Jean-Baptiste. They smuggle them over the border by night, avoiding the police patrols, for none of them have a passport. Sometimes they take them over the river on rafts made of wood and plastic drums, lashed together with twine woven from the banana leaf.

Adjo’s mother wonders if, on the day her sons return, she will even recognise them. Both will have grown into men by now. Her heart swells painfully at the thought. And she thinks of her daughter, Adjo – so clever, so young, with red string woven into her hair and the voice of an angel – still waiting, after all this time. And when the daily chores are done, and the red sun fades from the western sky, and the younger children are asleep on their double pallet in the hut, she watches Adjo as she stands perfectly still by the Great North Road, etched in the light of the village fires, singing softly to herself and praying for her brothers’ return.

For Adjo knows that the road is a god, a dangerous god that must be appeased. Sometimes it takes a stray child, or maybe, if they are lucky, a dog – crushed beneath some lorry’s wheels. But the traffickers take more than that; four children last year; three gone the year before. So Adjo sings;

Don’t let them come; please, this year, keep them away

– and she is not entirely sure whether it is to God or Allah that she prays or to the Great North Road itself, the sly and dusty snake-god that charms away their children.

By night the road seems more than ever alive; filled with rumours and whisperings. All the old, familiar sounds from the village down the path – the chanting, the drumming, the children at play, the warble of a radio or a mobile phone from outside the Chief’s house, where the men drink

tchouk

and talk business – now all these things

seem

so far away, as distant as the aeroplanes that sometimes track their paths overhead, leaving those broken vapour-trails like fingernail-scratches across the sky. Only the road is real, she thinks; the road with its songs of seduction, to which we sacrifice our children for the sake of a beautiful lie, a shining dream of better things.

She knows that most will never come back. She needs no songs to tell her

that

. The fishers of men are predators, with their shining lure of salvation. The truth is they come like the harmattan, the acrid wind that blows every year, stripping the land of its moisture and filling the mouth with a sour red dust. Nothing grows while the harmattan blows, except for the dreams of foolish boys and their even more foolish mothers, who send them off with the traffickers – all dressed in their church clothes, in case the patrols spot them and smell their desperation – each with a thick slice of cold maize porridge, lovingly wrapped up in a fold of banana leaf and tied with a piece of red string, for luck.

Money changes hands – not much, not even the price of a sackful of grain, but the baby needs a mosquito net, and the older one some medicine, and she isn’t

selling

her children, Adjo’s mother tells herself; she is sending them to the Promised Land. Adjale will look after them. Adjale, who every year brings news of her sons and tells her:

maybe next year they will send a card, a letter, even a photograph

–

But something inside her still protests, and once again

she

asks herself whether she did the right thing. And every year Adjale smiles and says to her;

Trust me. I know what I’m doing

. And though it’s very hard for her to see him only once a year, she knows that he is doing well, helping children along the road, and he has promised to send for her –

one day, very soon

, he says.

Just as soon as the children are grown. Four years, maybe five, that’s all

.

And Adjo’s mother believes him. He

has

been very good to her. But Adjo does not trust him. She has never trusted him. But what can one girl do alone? She cannot stop them any more than she could stop the harmattan with its yearly harvest of red dust.

What can I do?

she asks the road.

What can I do to fight them?

The answer comes to her that night, as she stands alone by the side of the road. The moon is high in the sky, and yet, the road is still warm, like an animal; and it smells of dust and petrol, and of the sweat of the many bare feet that pound its surface daily. And maybe the road answers her prayer, or maybe another god is listening; but tonight, only to Adjo – it tells another story; it sings a song of loneliness; of sadness and betrayal. It sings of sick children left to die along the road to Nigeria; of girls sold into prostitution; of thwarted hopes and violence and sickness and starvation and AIDS. It sings of disappointment; and of two boys with the scars of Kassena cut into their cheeks, their bodies covered in sour red dust, coming home up the Great North Road. The boys are penniless, starving and sick after

two

long years in Nigeria, working the fields fourteen hours a day, sold for the price of a bicycle.

But still alive

, Adjo thinks;

still alive and coming home

; and the pounding beat of this new song joins the beat of Adjo’s heart as she stands by the road at Kassena, and her feet begin to move in the dust; and her body begins to lilt and sway; and in that moment she hears them all; all those vanished children; all of them joining the voice of the road in a song that will not be ignored.

And now she understands what to do to fight the fishers of children. It isn’t much, but it

is

a start; it’s the seed that grows into a tree; the tree that becomes a forest; the forest that forms a windbreak that may even stop the harmattan.

Not today. Not this year. But maybe in her lifetime –

Now

that

would be a thing to see.

Walking home that night past the fires; as Adjo walks past the Chief’s hut; past the maize field; past the rows of pot-bellied henhouses; as she washes her face at the water-pump; as she drinks from a hollowed-out gourd and eats the slice of cold maize porridge her mother has left on the table for her; as she lays out her old school uniform, the white blouse and khaki skirt and the battered old football boots that she has not yet outgrown; as she lies down on her mattress and listens to the sounds of the night, Adjo thinks about

other

roads; the paths we have to make for ourselves.