Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (35 page)

Â

He goes on to promise that he will acquaint “rustic Courland” with Beethoven's music, and rhapsodizes about a girl who “has captured your Amenda.” In the letter, Amenda essentially charts a course for Beethoven, or confirms a course Beethoven was already on. Don't neglect sometimes to write broadly, Amenda said, not just for connoisseurs. After his serious first two opus numbers, Beethoven would issue a steady stream of lighter pieces in a range of media, some earning opus numbers and some not. At the same time, Amenda goes on, for your most important works, “you must educate them to your level.” In other words, Beethoven needed to teach people how to listen to his music. Haydn and Mozart had done the same in their day, but Beethoven's challenge to eighteenth-century taste was more aggressive than theirs.

The fervor of Beethoven's friendship with Amenda can be contrasted with the social divides and the tensions of his relations with aristocratic patrons like Lichnowsky and Lobkowitz, with his tendency to view performers like Ignaz Schuppanzigh as hardly more than servants, and with his bantering relationship with faithful minion Baron Zmeskall von Domanovecz: “Will the very high born personage, the Zmeskality of H[err] von Zmeskall, graciously condescend to decide where he can be spoken to tomorrowâWe are quite damnably devoted to you.” In another note of 1798: “My cheapest Baron! See to it that the guitarist [a friend of Amenda's] shall come to me today for certain.

Amenda

instead of paying

amends

. . . for his failure to observe rests, must let me have this [admirable] guitarist.” For whatever reasons, surely fondness among them, Beethoven was patient with the baron. They would never have a real fight, but now and then Zmeskall had to be taken down a notch:

Â

My very Dear Baron Muckcart-driver,

Je vous suis bien oblige pour votre faiblesse de vos yeux.âBy the way, I refuse in future to allow the good humor, in which I sometimes find myself, to be destroyed. For yesterday thanks to your Zmeskall-Domanoveczian babble I became quite melancholy. The devil take you, I refuse to hear anything about your whole moral outlook.

Power

is the moral principle of those who excel others, and it is also mine; and if you start off again today on the same line, I will thoroughly pester you until you consider everything I do to be good and praiseworthy . . . Adieu Baron Ba . . . ron ron/nor/orn/rno/onr/ (Voilà quelque chose out of the old pawnshop).

6

Â

That mock-offended but mostly jovial note is striking in several dimensions. The reference in bad French to the baron's eyes has to do with a viola-and-cello piece Beethoven had written for the two of them,

Duet with Two Obbligato Eyeglasses

, since both of them required spectacles to play it. The last line in parentheses indicates that the duet is enclosed by means of an arcane pun on

versetzen

, which can mean “to transpose” (as with music) or “to pawn.” The line about power as the moral principle of the superior man may reflect a philosophy or a momentary moodâBeethoven seems never to have written a sentiment quite like it again. Near the end of the note, he composes an alphabetical theme and variations on Zmeskall's noble title. These notes to Zmeskall are among many that suggest Beethoven tended to write letters later in the day, after composing, in high spirits from a glass or several glasses of good cheer. Wine had made his father merry sometimes, volatile at other times. His son followed suit. Quite unlike his father, however, nobody ever reported Beethoven as a sloppy or abusive drinker or found him passed out in the street.

Â

In August 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte's inexorable rise was halted for the moment when British admiral Horatio Nelson destroyed a French fleet in the Battle of the Nile. That galvanized a new coalition of Britain, Austria, Russia, and Turkey, which for a while promised to end the French rampage. There is no record of how Beethoven viewed all this trouble, though he could hardly have been unaware of it. He remained happily and profitably at work that year.

There was a flurry of piano sonatas, natural enough given that it was his instrument, that piano sonatas were among his most salable items, and that he did not feel intimidated by precedents in Haydn, Mozart, Clementi, or anybody else. Piano sonatas were also laboratories where he could experimnt with new ways of putting pieces together, with new sonorities and new voices. So it was with the three modestly scaled but significant sonatas of op. 10. All of them have a singular expressive pattern: sprightly-unto-joking outer movements set off by second movements of a poignancy and depth that intensify throughout the opus.

Op. 10, no. 1, in C minor, amounts to another stage in Beethoven's ongoing process of finding his sense of this key. To a degree, he would discover who he was as an artist by way of C minor. Still, the Beethoven voice the world would come to know is not quite that of this sonataâthe fiercer moments of the op. 1 Trio in C Minor are closer. The C Minor Sonata has an opening theme darting upward in dotted rhythms answered by a quiet, poignant gesture, introducing a movement largely impulsive and headlong, spaced by flowing lyrical interludes, while the gentle slow movement in A-flat major is a touch backward-looking,

galant

, its themes sprouting ornaments in Mozartian fashion. A short finale turns the driving force of the first movement into fun and games, the themes scampering along. At the coda, there is a quiet and thoughtful moment recalling the second movement.

No. 2, in F major, begins with a little hop and proceeds in a series of fits and starts, characterizing a movement wry and lively, with moments ironically grand and

furioso

. Rather than a slow movement, what follows is an oddly pensive and flowing, at times haunted, unscherzo punctuated with offbeat accents. Whatever griefs shadow those pages are eased by a good-humored finale, the main theme folklike and stamping.

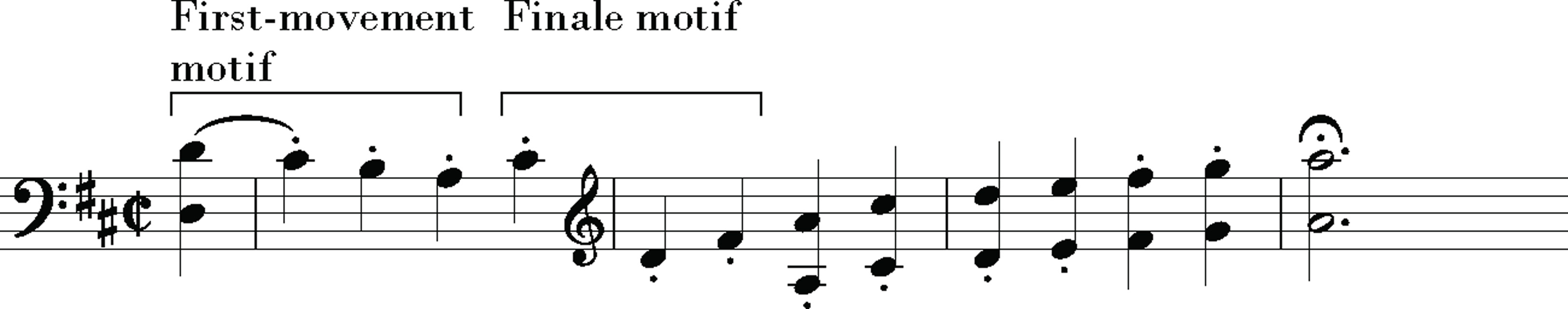

Then comes the stunning D-major, no. 3 in the set, the finest sonata and one of the most individual works he had produced yet. The progress of its four movements echoes the expressive shape of the previous two, but the comedy in the first and last movements is ratcheted higher, framing an unforgettable song of sorrow in the slow movement. Part of the humor in the outer movements is the stinginess of material: the first four notes of the dashing opening theme (a bit of descending scale) will dominate the first movement to a point of absurdity; the next three notes (a rising half step, then jump of a third) will dominate the finale.

Â

Â

The twitchy and obsessive opening movement is rarely able to escape its scrap of scale, whether it is running up or running down. The last rush to the cadence is laugh-out-loud funny. (Whether intentional or not, that ending is also a near-quote of the opening of Mozart's lighthearted Piano Concerto in B-flat, K. 450.)

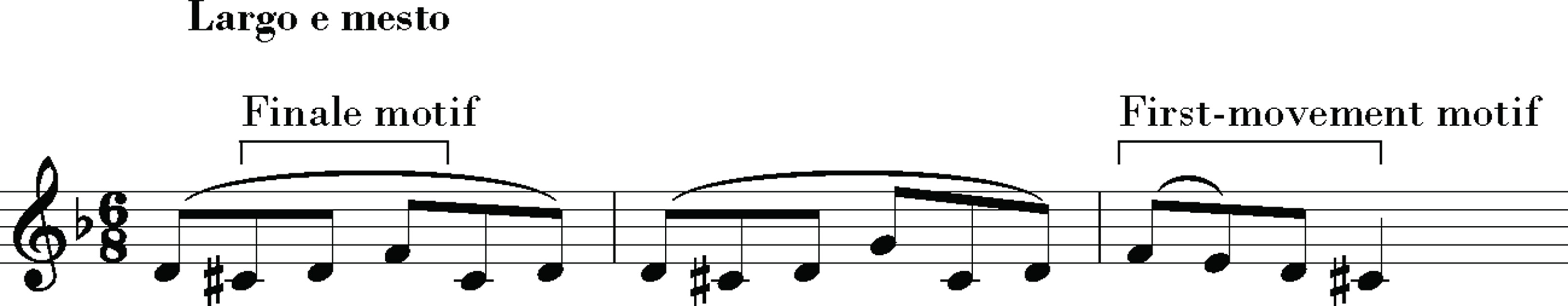

The D-minor slow movement is marked Largo e mesto, slow and mournful. That describes one of the most mournful works of music written to its time. It seems locked in a trance of sorrow, at once individual and world-encompassing. Moments of hope soon sink; the main relief is in bleak, trembling silences. What follows, a delicate

minuetto

, feels like a pulling together after the suffering of the slow movement. Then the droll finale, an Allegro rondo, begins with a couple of can't-get-started stutters followed by sort of a sneeze. The stuttering figure is relentless and steadily funnier; earlier movements are recalled in more sober moments that don't impede the high spirits.

What did Beethoven mean by these experiments in antithetical emotions? A number of things beyond a simple desire to intensify contrasts. In the world at large, this kind of juxtaposition was a leading topic of debate among German thinkers. It was an aspect of Shakespeare's tragedies that, with the advent of new German translations, had troubled German eighteenth-century aesthetics: how can a mingling of tragedy and comedy be said to have unity when they are in the same work? For his part, Beethoven did not make contrasts for the sake of momentary effects, without reference to the whole. Already in op. 1, he was shaping his works as a single narrative, a coherent journey through a series of characters and emotional states. In the D Major Sonata, that paradoxical journey has particularly significant implications.

Again, the very beginning of the D Major's comic first movement sets up two motives that will dominate the piece. The theme of the tragic slow movement is made from those two motives:

Â

Â

Who knows what Beethoven thought of the motivic connections among these contradictory worlds of first and second movements. But what the D Major Sonata suggests, in terms philosophical and psychological, is that the material of comedy and tragedy is the same, that joy and suffering are made of the same things. Here is something articulated in tones that reaches a far-sighted human wisdom.

Â

In the elegant and ingratiating (Ã la Mozart, in his light vein) op. 11 Trio for Piano, Clarinet, and Cello, there is no attempt at wisdom or innovation. The clarinet serves in the usual position of the violin in a piano trio. (In hopes of better sales, Beethoven supplied an optional violin version of the clarinet part.) For a finale, he wrote variations on a well-known perky tune from an opera by Joseph Weigl, earning the piece the nickname

Gassenhauertrio

, or “Popular Melody Trio.”

The presence of Mozart also hovers over the more substantial, yet nonetheless still cautious, three violin sonatas of op. 12. Here, as usual, Beethoven used what he considered the best models for a given medium and genre, and, as usual, they left traces in the music. Mozart was the main model, because his violin sonatas were supreme in the repertoire.

7

There would be no record of a commission for these pieces. It appears Beethoven wrote them because he wanted to try his hand at the medium. They may also have been helped along by his acquaintance with the French virtuoso Kreutzer in Vienna in early 1798. Kreutzer and Beethoven gave a private concert at Prince Lobkowitz's in April, and Beethoven was duly impressed with this celebrated exemplar of the French violin school.

8

That violin tradition would remain another model for him. Around the time of the Kreutzer concert, he finished the second and third sonatas.

To ears schooled in later Beethoven, op. 12 would sound like relatively light excursions in a current style. Beethoven was, in other words, still not ready to mount a challenge in a medium that Mozart dominated. All three violin sonatas are in major keys and in three movements, in tone ranging from lighthearted to playful, though no. 2 has a beautiful, melancholy slow movement and no. 3 is a degree more serious. As he had done in earlier, more backward-looking works like the first two piano concertos, Beethoven slipped into these pieces some startling harmonic excursions. In the first movement of Sonata No. 1 in D Major, he surrounds the main key with mediants, keys a third away in each direction: B-flat and F. In the fairly short course of the first-movement development section of No. 3 in E-flat, he ranges into the wilds of flat keys: C minor, G minor, B-flat minor, E-flat minor (his old favorite), even C-flat major.

9

That was pushing things in those days, and he would get slapped for it in one of his first important reviews. The premiere of one or more of the sonatas probably came in a Vienna concert of March 1798, Beethoven and Ignaz Schuppanzigh presiding.

10

In one way and another, creatively and professionally, the ground was prepared for another piano sonata finished in 1798, the first work of Beethoven's to bid for the term

epochal

. It was published the next year as op. 13,

Grande Sonate

Pathétique

.

Â

From its glowering opening chords, the

Pathétique

paints pathos like no work before: naked and personal. Here Beethoven found a kind of music that seems not like a depiction of sorrow but sorrow itself: