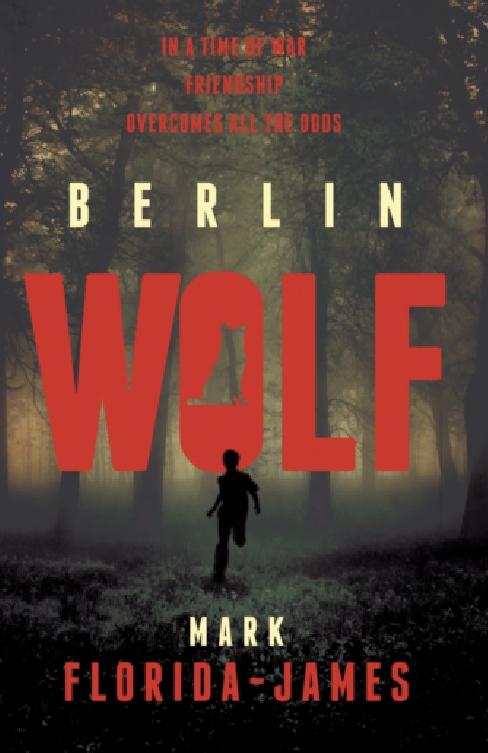

Berlin Wolf

Authors: Mark Florida-James

Mark Florida-James

Copyright © 2013 Mark Florida-James

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study,

or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in

any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the

publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with

the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries

concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park

Kibworth Beauchamp

Leicestershire LE8 0RX, UK

Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299

Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

ISBN 9781783069712

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

Converted to eBook by

EasyEPUB

Inspired by Maisie, our very own wolf and the best dog ever, and Ela Clark (15

th

May 1925 â 22

nd

May 2011), a dear friend who lived through those terrible times and courageously fought the Nazis.

* * *

With many thanks to Ela and Ann Clark for their feedback and encouragement.

* * *

In memory of my brother, Anthony (10

th

October 1984 â 1

st

October 1989).

* * *

Dedicated to my wonferful wife Jackie and our adorable dogs past and present, Maisie, Woody, Charlie and Gulliver.

Bathing Beach, Lake Wannsee, Berlin 15th November 1941

âGood boy Wolfi! Good boy! Not long now.' Peter Stern stretched out his hand in the darkness and stroked Wolfi's head. âPlease come soon,' the young boy prayed.

They had been standing as still as possible for many hours. His feet and hands were numb from cold and he was hungry. His warm home with its larder full of food was just a short walk away. The fifteen-year-old and his dog were huddled together in a thick glade of trees alongside Lake Wannsee. Close by, his parents Isaac and Sara, were shivering, as much from fear as the biting cold. No-one had dared speak for over forty minutes. At last, it had turned dark and they could relax a little.

The plan had seemed so simple. They had walked from the family home on Schillerstrasse, around Lake Schlachtensee and then west to the woods surrounding Wannsee, Berlin's huge play park. To the casual observer they were a family on a picnic outing with hamper, knapsack and the family dog. They were dressed appropriately for the time of year with overcoats, hats and scarves. Even Wolfi had a coat of types. Possibly the most valuable dog coat ever, for sewn into the lining was Sara's small, but precious collection of jewels, heirlooms handed down over many years. Had anyone listened closely they would have heard a slight rustle as she walked, causing the wads of Reich marks hidden in her petticoats to rub together. Papa had reckoned there was less chance that Wolfi or Sara would be searched if stopped. Each had their own identity card, just in case anything went wrong. There was no point hiding these. They were required to carry them by law. In his heart Papa knew that they were worthless so long as they were stamped with the red letter âJ'. âJ' for Jew.

As they had made their way by the familiar streets from their home to Lake Wannsee they were nervous of meeting neighbours. The sort of neighbour who might notice their sudden weight gain or, the excessive sweating caused by additional layers of clothes.

At least they had been lucky with the weather. Berlin winters were often very harsh and it was not unknown for there to be deep snow on the ground in the middle of November. A picnic on a dry, sunny, winter's day would not attract any undue attention. Berliners are a tough breed. A picnic in the snow might arouse suspicion. Had the weather been unfavourable the plan had been to pose as a family going sledging in the park. This had the disadvantage that there would be no reason to carry any sort of luggage.

Everything was fine until, rounding a corner from Fisherhüttenstrasse, they came across a mob of SS men.

âPick it up! Pick it up! Faster you lazy pig!' one screamed hysterically.

The unfortunate victim was an elderly Jewish man. He was easily identified by the yellow star on his lapel. Every time the old man bent over, one would kick him sharply in the backside and scream at him again. It was a sadly familiar scene in Berlin. The Stern family desperately wanted to help. They dare not jeopardise their escape. With a deep sense of shame they tried to avoid eye contact and continued their journey.

âAhh!' the elderly Jew gasped and clutched his heart as he fell to the ground.

âOh no!' Sara Stern cried out and stepped towards him. The leader of the mob of four SS men, more of a boy than a man, instantly turned towards her. He looked her up and down and then quickly surveyed the rest of the group.

âSo you feel sorry for the Jew. Maybe you are also Jews. Show me your papers!' he demanded.

Isaac, Sara and Peter hesitated for just a second. If he had not noticed the faded patch on their clothes where the Jewish Star had once been sewn, their passes would betray them. The delay was unacceptable. Patience had long since deserted Germany. The SS man removed his revolver from its holster, pulled back the safety catch and cocked the hammer.

âPapers! Quickly!' he screeched. The gun was pointed at Sara's face, just a few terrifying centimetres away.

Before anyone could respond to the threat, Wolfi fell on one side, rolled over and put his paws in the air, as if dead. It was his best trick. The SS man fell into fits of laughter.

âAll right you can go. No Jew could teach a fine German dog such a good trick.' He was still laughing as he put away his gun. He patted Wolfi on the head and, without waiting further, the family hurried on. To their relief the old man struggled to his feet. His tormentors were bored with their game and he was allowed to leave.

Once around the next corner Isaac stroked Wolfi warmly.

âI knew it was a good idea to bring you.' As he spoke he felt a pang of regret and guilt. He had not yet told Peter. His best friend Wolfi could not go with them.

* * *

During the daylight hours they had sat by the lake on a blanket, with picnic basket in view. Peter played with Wolfi and the rest of the family ate and drank in minute amounts. They had no idea how long their journey was to take. Periodically they had packed up and moved some distance away to try and avoid unwanted attention. That had worked quite well and had been relatively easy. They had even managed to sneak into the woods unnoticed.

Since then, the long hours standing in the dark and cold, remaining as silent as possible and encouraging Wolfi to do likewise, had been very trying. Even the sound of shuffling from one foot to the other to keep warm seemed to magnify and echo across the surface of the lake. Isaac thanked their luck that most other visitors had left early in the gloom of the November evening.

* * *

Now as he hugged himself for warmth, Isaac wondered how Peter would react when he realised that Wolfi must stay behind. Would it have been better to have left Wolfi at home? Someone, even a Nazi, might have adopted him. He was after all a fine âGerman dog'. Wolfi had more than served his purpose as he had been part of the cover story. Who attempts to flee in secret with a dog? This had to be the end of the line. The success of their escape would depend on remaining as inconspicuous as possible.

Oblivious to his father's dilemma, Peter rubbed Wolfi's furry black ears. He remembered the day five years ago when Wolfi arrived. As always an expectant son sat at the bottom of the staircase, waiting for his father to return from the city. On this occasion he was particularly impatient. It was his tenth birthday and he expected Papa to be clasping a large present of some sort. Maybe the kite he had seen in the toyshop or the model sailing boat? For some reason his father was even later than usual. Hopefully his work at the bank had not held him up? Not today of all days? To make matters worse, when Papa did finally push open the heavy wooden door he had nothing in his hand, only a snow-streaked umbrella.

The boy sat back on the step, trying to hide his disappointment. Surely Papa had not forgotten? And then he noticed it. Inside Papa's huge overcoat something was moving. The tightly woven, woollen material rippled in places, like the surface of the Berlin lakes in the wind. Peter was fascinated, following every movement. The ripple moved to Papa's lapel and out popped a black ball of fur. The fur ball grew two small pointy ears and a pink tongue that was clearly too long for its mouth. An ear flopped to one side, whilst the other stood very proud and erect. Two blue-grey pools reflected in the light of the hallway. The excited boy sprang from the step as a highâpitched bark confirmed that it was indeed a puppy.

When finally Papa was able to take off his hat and coat and remove the black bundle, Peter was surprised to discover that the rest of the animal was the same size as the head. He did not care. He had a puppy, the dog he had wanted for so long. He hugged it to his chest, almost smothering it. This was the best present ever. In spite of looking more like a little bear cub than a wolf, Peter had named it âWolfi' after one of his favourite stories. After all he had joked âif I am Peter he must be the wolf'.

Within six months the small bundle of fluff that Papa could stretch out in one hand was now a medium-sized dog. Eighteen months later, at the age of two, he was a fully grown, entirely black, shaggy, long-haired dog. He had pointy ears that swivelled towards any noises, a long well-defined snout, sparkling grey eyes and a thick, bushy tail that was never still. His teeth, when exposed with a growl, struck fear into almost all who saw it. And indeed he looked very like a wolf. In appearance he was the shape of the famous German shepherd dog. Some thought he might in fact be a Belgian shepherd, cousin of the German variety. His breeding made no odds to Peter. He was his best friend.

Wolfi and his young master were seldom apart, except when Peter went to school or synagogue. Every school day morning he would rise early to take Wolfi for a walk in and around the lake and in the woods, even in the dark of winter. On his return from school he would greet Wolfi first, then acknowledge his mother (and father if present). Once changed out of his school uniform, he would take his best friend out for another walk.

On weekends or holidays they would sometimes spend almost all morning and afternoon in the woods around Lake Schlachtensee making camps, swimming or fishing in the clear waters of the lake. If the severe Berlin winter was in full flow they would play together in the conservatory, with Peter teaching Wolfi tricks. How to sit, lie down, play dead and even sing along to Papa's opera records. The singing was for some reason not so popular with Mama or Papa.

At first Wolfi was restricted to the conservatory and the garden, then gradually, bit by bit, the boundaries were extended until he was allowed in virtually all the rooms of the house. He would sneak onto a comfortable chair next to Peter and lie across his legs; or slip into his bedroom having pushed open the door with his nose and then clamber onto Peter's bed, where he would sleep peacefully by his feet. He was even known on occasions to have found his way onto Papa's lap when he was snoozing after lunch in his favourite leather armchair. Papa had always claimed that âthe dog' as he referred to Wolfi, had jumped up without his knowing. No-one believed him.

As each boundary was pushed back a little further, the affection of all the family, Mama, Papa and Peter, grew for Wolfi, much though the adults tried to resist it.

As these happy memories filled Peter's thoughts, the gentle chugging of a motor launch was heard approaching the shore.

âAre you sure we can trust this man?' Sara whispered to her husband. She was clearly anxious. Their safety depended on the captain of the boat they were about to board and they knew so little about him.

âYes, though in any case we have no choice.' Isaac was not entirely convinced by his own answer. He had only met the man the night before through an acquaintance at the bank where he worked. He was introduced to the Captain of a tug boat transporting coal along the waterways of Berlin to the west at Lübeck. For a smallish fortune he would convey them to the northwest coast where they should be able to buy a passage on a ship to safety.

The Captain, despite his rough demeanour, appeared trustworthy. He was no particular Jew lover, he just hated the Nazis. He had been interned for a while in the early years of the regime for his communist sympathies.

He had arranged to meet them on the eastern shore of the great Lake Wannsee, at the far end of the pleasure beach where once Isaac and his family had enjoyed long, care-free summer days. The same beach from which they were now banned. They were to meet at the pontoon at nine in the evening. No signal was to be given as the slightest unusual noise would travel far across the lake and even a single light would be readily visible in these times of routine blackouts.

All this had been agreed the previous evening. Any doubts Isaac had as to whether they should attempt to flee were dispelled by the Captain. When asked about the rumours of what happened in the East, the Captain had taken the pipe from his mouth, saying gravely,

âI have seen for myself what goes on. You need to get your family out of Germany.' Isaac had departed without delving further into what the Captain knew.

Without wasting any time they quickly gathered their few belongings and hurried out of the trees and towards the pontoon. Wolfi was on a short leather lead. He was excited to be moving again. Thankfully the only indication of this was a greater bounce to his step.

âWhat's this? This can't be our boat,' Isaac murmured and wondered whether they should retreat into the woods.

Only as he spotted the Captain at the tiller did he realise that it was indeed their boat. It was not, however, the canal boat or tug he had expected. This was a small pleasure cruiser, the type that would often be seen on Lake Wannsee, a type not so usual on the canals of the more industrial part of the city. Most worryingly this was a pleasure boat with all-round visibility. Passengers could sit in comfort and view the scenery, equally they could clearly be seen from the outside. Worst of all there was no below deck. At least it was an overcast night with little natural light. Isaac stepped on board and beckoned to his family.

âI thought you promised us a tug, not a pleasure boat for all to see.' The desperation was obvious in Isaac's voice.

âI can't bring a tug this far down the lake. There isn't any need for such a boat as that here. No-one will notice a tug on the canal at night time. They would at this end of the lake however. We'll change vessels when we get onto the narrower part of the river.'

âYou should have told me that last night,' Isaac muttered, unhappy with the Captain's explanation. The sailor shrugged his shoulders.

Momentarily distracted, Isaac had forgotten about Wolfi who was now at the bow of the boat with his son.

âHold on,' said the Captain, âyou can't bring that mutt.'

As Peter approached the Captain, Wolfi began a low growl, becoming unusually agitated.

âHe's right,' said Isaac. âYou had better set him loose.' Even as the words left his mouth and, in spite of the darkness, Isaac could see the crestfallen look on his son's face.

âQuiet boy! Quiet!' Peter urged. Thankfully he managed to calm Wolfi, who stood head cocked to one side, wondering what was going on. âPlease Papa! Please!' Peter begged, âI cannot leave him, I will not leave him.' He could not imagine any new life without his dog, even if it meant disobeying his dear Papa.