Black Pearls (10 page)

Authors: Louise Hawes

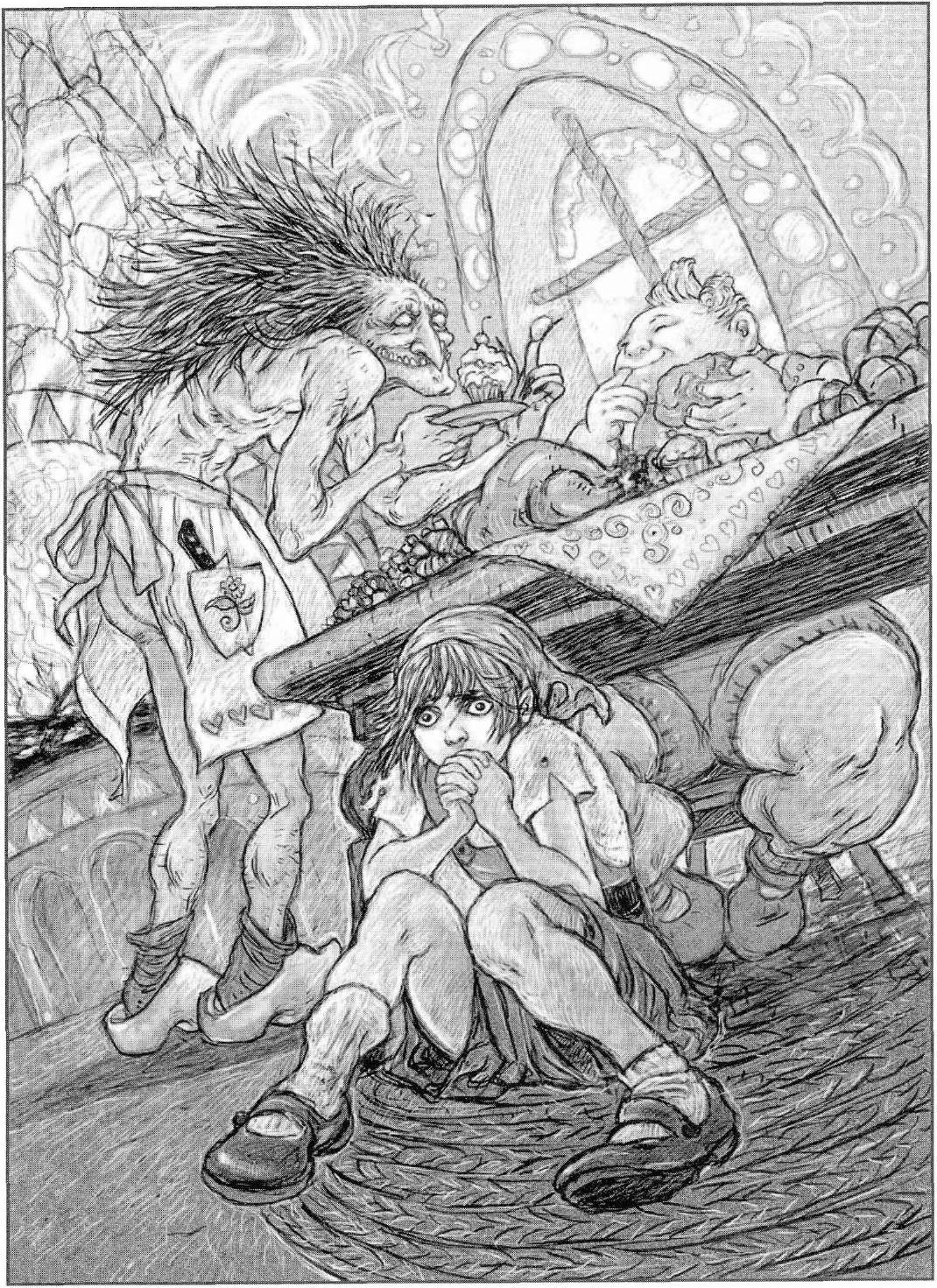

Until Hansel laughed. He even left off savaging the ginger man's body. He put his hands on his knees to steady himself, then rocked back and forth, roaring. The tears streamed from his eyes and down his newly dimpled cheeks. Back and forth, back and forth he rocked, until the room filled with his mirth and Gretel feared the witch would hear.

"Stop!" she commanded. "Stop and hear me." When he slowed a bit, she pushed her words in between the spasms of laughter. "Does she not feel your wrist each day?"

"Ay," he told her. "'Tis but to take my hand. She is wont to pat me often." He glared at his sister, but his tone was softer, almost a purr. "She cannot see at all well, Mother. She must touch where others look."

"She wants you fat enough to cook." Gretel was no longer careful how she put the matter. "When you are done, she will roast you in the oven."

But Hansel looked past her, or through her, she could not say which. "She has a right soft touch, Mother does," he said.

"She has told me!" Gretel stamped in frustration, tears in her eyes. "She has said it to me!"

Hansel no longer glared; his expression approached pity. "You are making it up," he told her. "Because she does not love you as she does me."

"'Love'!" Gretel was blinded by tears, by disbelief, by the word itself. How could he use such a word here, in this house? How could he use it about such a woman?

"She says I have nobility," he told her now. "When she sets eyes on me, 'tis as if she see a duke or a prince." His own fierce eyes fastened on Gretel again. "No one has ever looked upon me that way."

"Butâ"

"And you shall not take this from me for spite."

"It is notâ"

"Go back to Father and our stepdame, if you wish." He ab most rose from the bed, but perhaps his legs were not equal to the task of bearing his weight. He sank down to his bed again, sending more marbles across the floor. "As for me, I would rather die than go back to that thin gruel and those harsh words." If it was not loyalty that shone in his eyes, it was at least pure contentment. "I shall not leave Mother."

Gretel despaired of changing his mind. Of saving his life. But still she took the twig from her pocket. "Take it," she told him. "If you give her this instead of your wristâ"

"Enough of your wiles, girl," he scolded. "Go back to the hearth."

"âshe will think you have lost weight."

"Get out! Get out, before you ruin it all!"

"And she will feed you even more."

Her words found their mark. Gretel saw her brother stop, lean back on one round elbow, and consider. She plunged ahead, heaping him with delights. "Crumpets and pasties and those littie blue eggs you like. Rabbit and trout and all manner of fowl."

He reached for the twig she proffered, reciting dreamily, "Pancakes and almond tarts, puddings and jam."

Gretel nodded. "More of everything," she agreed. "She will feed you twice, maybe three times as much as she does now."

When they heard the witch's shuffling footstep in the hall, Gretel had won only half what she'd hoped for: Hansel was delighted with the plan of tricking the old woman into feeding him more, a plan that, although he didn't know it, might spare his life. But she had still found no way to persuade him to leave that cursed house.

Gretel climbed out the bedroom window and circled back to the kitchen. The witch unlocked the door to visit her plump cherub, unaware of the visitor who had left him seconds before. And so more weeks passed, and months as well, time that left Hansel plumper and Gretel and the witch more famished. For as the witch grew hungrier, she fed the girl less, too, and by the time she decided to put an end to her fast, neither of them could remember what a full stomach felt like. Gretel, as she lay by the hearth at night, her poor insides churning and empty, remembered the way Mother, at the end, would push away the trays Gretel brought.

I will have none of that,

she'd say.

Just sing me another song, sweet. 'Tis that will fill me up.

And sometimes it was enough to put her to sleep, humming the old song, the lullaby Mama craved.

"There be no use," the witch said one day, as Gretel had known she must. The crone threw her book of spells at Gretel, though it fell short of its mark and skittered along the floor. "I have prayed and chanted and fed the boy until I am worn with toil." She waved a frail hand at the girl. "I may as well eat a skinny thing like you."

She rose then and, with a horrible finality, walked to the drawer where she kept her knives and skewers. "I have conjured cornmeal and compotes, peacock and ham hocks. I have summoned up soups and stews. Souffles and crab cakes. But still he loses flesh." She sharpened one of her longest, cruelest knives on a whetstone, brushing it faster and faster across the oiled rock. "I have coddled and spoiled him and emptied his foul pan."

She held up the gleaming knife now and, before Gretel could

pull away, sliced off a lock of the girl's hair. "Sharp enough to do the job," she said, grinning at the curl of fine hair in her hand. "I will have him this day. I can wait no longer."

But when she led him to the table and bade him wait while she stoked the fire, even when the oven got so hot they could feel it across the room, Hansel did not fear the witch. He sat, his haunches overflowing the small bench beside the trestle, and smiled. "What treat shall we have tonight, Mother?" he asked. "It must be a feast if you cannot carry it on a tray." He gripped his spoon and knife, as if the food were already in front of him.

Did he call the crone Mother to please her? Gretel wondered. Or did he nurse some dark angel of his ownâthe image of a mother made of yams and comfits, chops and pies?

"There shall be no feast until I can make this oven hot enough, my lamb," the witch told him. "Perhaps you could come see if the flue is blocked." She gestured toward the fiery oven. "This old frame is too stiff to bend so low."

If her frame was too old, the boy's was surely too broad. But he stood with what alacrity he could muster and went to her side. "Let me see, Mother," he said, bending down, peering into the blood-red innards of the stove.

Just as Gretel dreaded, the witch rushed at her brother, a look of such fierce yearning on her face that for a moment the girl stood paralyzed. But then, just in time, she reached out and pulled her brother away from the stove, and what had started could not be stopped. The old woman, hands outstretched to push her boy-roast in the oven, fell into the flames herself. The children watched in horror as, blind with agony, the witch crawled deeper into the fire instead of finding the way out. Hansel put his hands in to reach her, but the witch, in her anguish, writhed out of his grasp. "Fools! Fools!" she wailed as the smoke and heat did their work. Once more Hansel reached into the flames, and once more failed to catch hold of the witch before the fire forced him back. "Fools! Fools!" And then her mouth was lost, her skin, her need to cry out at all.

There was silence, blessed silence until Gretel noticed her brother's hands. "Here," she said tenderly, reaching for his burned fingers. "Let me get some salve."

But Hansel pulled away from her. "No!" he screamed. "Do not touch me. Do not dare touch me."

"But your hands are terribly burnt." Gretel looked up from her brother's hands to his face, and lost her breath. What she saw there was hate, burning and bottomless.

"You killed her!" Hansel's skinless hands were balled into fists, and he was crying as she had never seen him cry before.

"But Brother," she said, "she would have pushed you in." She backed away from his eyes, for they seemed to give off a heat like the oven's.

"You were jealous!" he screamed at her, anger turning his round cheeks pink as beef fillets. "It was you she kept working and me she fed."

Gretel backed toward the stove, which still smelled of burning flesh and sulfur. "You couldn't stand to see one of us safe and happy and protected," he yelled. "Only one of us, sister mine. That was it, wasn't it? Only one!"

"Of course not," she told him, hearing herself whimper, try ing to escape those eyes even as the heat from the oven grew behind her.

"You wanted to drag me back home." He was no longer screaming but spoke as slowly, harshly, as a wheel turning on cobbles. "You wanted me to be poor again, to drink soup made of water."

The stove's flames, fed by the witch, leapt higher now and Gretel tried to move toward Hansel. But he pushed her back. "Mother loved me more than anyone ever has"âslowly, relentlessly, he advanced toward herâ"but you could not bear it, could you?"

"No! Surely, you knowâ"

"I know that your mewling angel never fed us as Mother did." He bore down on her, raw hands shaking, his face filled with rage and tears. "I know that no one will ever care for me as she did."

And then he was on her, but not before someone else barred the way. Gretel's angel, sudden, soundless, stood between brother and sister. Just as the boy tried to push Gretel backwards into the flames, the angel with their mother's face stopped him. A white-hot light surrounded it, steamed off the milk-white shoulders and wings. The finger it pointed at the boy, Gretel knew, was molten. It touched Hansel lightly on the chest and he screamed in pain. For a minute he hesitated, but, staring right through the angel, glaring at Gretel, he charged again. Growling with fury, he hurled himself at her, and if her angel had not pulled her away, it would have been the end of her. Instead, it swept Gretel up, as if they were dancing, and whirled her away, while Hansel raced headlong, screaming, into the flames.

When she set out for home, Gretel took some of the witch's cooking pots and a basket of food that would only go to mold if she left it behind. She could not carry more because her hands still ached from the flames she had braved at the end. When her brother fell into the oven, she had tried to pull him out. With no more thought to her own safety than a loyal dog protecting its master, she had leaned against the poker-hot opening of the stove and reached into the fire. But the searing pain, the breathless heat, brought her to her senses. She pulled back and watched in horror as Hansel rushed to his make-believe mother, as he picked up the flaming husk that had been the witch. As the skin ran like melting wax from his arms, he crumpled to the oven floor and raised his hands above his head as if surrendering to the roaring tongues that devoured him, bit by bit.

The thorny brambles had dissolved as soon as the witch died, and Gretel now made her way easily back into the woods through which she and Hansel had wandered before the old woman had trapped them. As she walked, the girl found ivy and chickweed to make poultices for her hands and for the bright red scar that crossed her waist where she'd leaned against the stove. Though she had no idea how far or which direction she and her brother had traveled, she was not afraid. Each night her angel leaned over her dreams, kissed her burning hands, and whispered the way to take next morning. By the time she reached her father's house, spring was coming on; tender shoots curled out of the ground, and birds flew once more in packs so thick they peppered the sky.

The old man, for old he suddenly seemed, was outside chopping wood as Gretel came up the rise toward the cottage. When he saw her, he dropped his ax and went mad with joy. "Gret, Gret!" he called, folding her to him, making the pots she carried clank and clatter. "You are home. You have come home at last!"

When she shrank back, peering toward the dark cottage, he shook his head. "You have naught to fear, child," he told her. "Your stepdame fetched poison berries from a fair on St. Joseph's Day. They gave me a fearsome bellyache, but they stole the life clean out of her."

"She is dead, then?" Gretel had seen enough death of late; the news gave her little joy.

"Ay," her father told her, linking his arm through hers, leaning on her as he had never done before she left. "But let us talk of pleasant stuff. There be time enough for sorrow." He led her to the door of the house, then looked behind her, toward the rise she had just climbed. "Say where your brother is and when he will join us here."

The time for sorrow came sooner than he must have hoped.

For Gretel told him how brother and sister had found the witch's house but only one of them had left it behind. She told him about her angel, and how it had saved her from the fire that killed both the old crone and Hansel. It was clear, though, from the way her father listened to the tale, the way he held his head in his hands, that he did not believe her.

"I tried to save him, Da. Truly, I did." But when Gretel held up her hands as proof, she saw how her angel's kisses had healed them, how they looked as white and smooth as if she had worn gloves along her rough and tangled way.

Father's eyes, the way they fell from hers, told her what he thought. "Hunger can drive God's love from our hearts," he said. "It can turn us into beasts." He stood beside Gretel, staring at the empty, sloping hills. "When times were still hard, not two days after we left you lambs in the woods, your stepmother tried to steal a crust from me. She came at me while I slept, slipped her hand into my pocket like a thief. Taken sudden that way, I struck her hard across the mouth.