Black Sea (21 page)

Authors: Neal Ascherson

Chapter Four

Wax for women, bronze for men.

Our lot falls to us in the field, fighting,

but to them death comes as they tell fortunes.

Osip Mandelstam, Tristia'

WITHOUT A MAN

upright on a horse, the landscape of the Black Sea grasslands seems incomplete. The novels, from Tolstoy's to Sholokhov's, have been read; the films watched. But this was once Amazon country, and the very maleness of the Cossacks is in reality a discord with the past.

Among the nomads of the Pontic Steppe, women were at times powerful: not in the condescending male sense of silky persuasiveness in beds or over cradles, but directly. They ruled; they rode with armies into battle; they died of arrow-wounds or spear-stabs; they were buried in female robes and jewellery with their lances, quiver and sword ready to hand.

In their graves, a dead youth sometimes lies across their feet. A man sacrificed at the funeral of a woman? This could not have happened in the Graeco-Roman tradition we call 'European civilisation', where - as the German film-maker Volker Schlôndorff once said — every opera about human transcendence requires the sacrificial death of a woman in Act Three.

To say 'the Amazons existed' is too easy. What is fair to say is that the Greek story about a race of virgin women warriors, mounted and firing arrows from the saddle, still looks like myth but no longer entirely like fiction. A hundred and fifty years ago, those same Victorian scholars who taught that Herodotus was a liar dismissed his and other versions of the Amazon story as childish fantasy. Since then, archaeologists and structuralist critics have both concluded

that Herodotus was more sophisticated than the Victorians supposed. His statements about material and spiritual culture in the Pontic Steppe continues to be confirmed by research, as we have seen. Where he did invent, it has become clear that he did so in a secondary, 'non-fictional' way: assembling shreds and tatters of diverse narratives from the past (which would otherwise have perished entirely) into a collage, a new presentation whose impact he had calculated with some care.

Writing in the fifth century BC, Herodotus started with old Amazon tales known to most Greeks and then assimilated them to new narratives which had come to him — second-hand, third-hand — from his oral sources, most of them apparently colonial Greeks on the Black Sea coast, if not from Olbia itself.

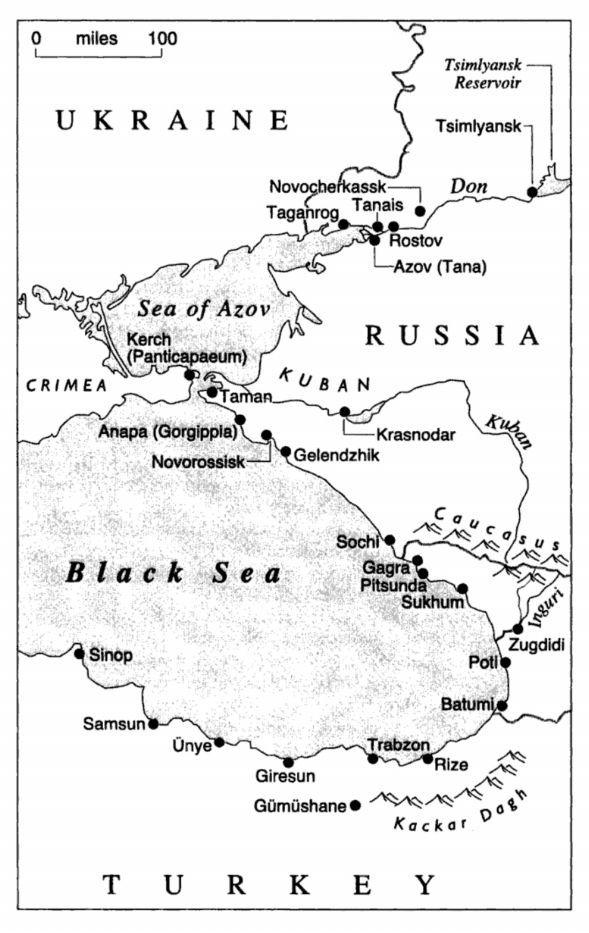

After the Trojan wars and the death of their queen, Penthesilea, the Amazons living on the south shore of the Black Sea had been overcome by the Greeks and herded into prison-ships. But they mutinied, killed their guards and finally landed somewhere on the Sea of Azov. Here they at first fought the Scythians but eventually mated with them, settling 'three days' journey from the Tanais eastward and a three days' journey from the Maeotian lake [Sea of Azov] northwards' and becoming the nation of the Sauromatae. 'Ever since then the women of the Sauromatae have followed their ancient usage; they ride a-hunting with their men or without them; they go to war, and wear the same dress as the men.' Thus wrote Herodotus.

It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century, when archaeological techniques were still perfunctory, that Russian excavators in the Pontic Steppe began to register that some of the warrior skeletons under the

kurgans

were female. The first of these discoveries was made in a tumulus in Ukraine, near the middle Dnieper, by the amateur Count Bobrinskoy who knew a bit about skeletal anatomy. But gradually the bones of the women warriors, as they were recorded on the map, began to cluster in the region north-east of the Don, the land of the Sauromatians in the time of Herodotus. Further east, in the plains between the Ural and Volga rivers, nearly a fifth of the female Sauromatian graves dated between the sixth and fifth centuries BC have been found to contain weapons. Scythian graves all over southern Ukraine have revealed women soldiers, sometimes buried in groups, equipped with bows, arrows and iron-plated battle-belts to protect their groins.

Later still, it became clear that the Sarmatians, who began to displace the Scythians from the Black Sea coast in the fourth century BC, also shared military and political authority between men and women. Sarmatian women burried by the Molochna River lay in scale-armour corselets, with lances, swords or arrows. The young Sarmatian princess buried at Kobiakov on the Don with her treasury of cult jewellery — a whole Iranian pantheon of animal and human figures made of gold — had her own battle-axe placed in the tomb beside the harness of her own horse-team.

Two conclusions seem to emerge. One is that Iron Age societies inhabiting the Black Sea-Volga steppes in the time of Herodotus and afterwards provided for a least some military and political parity between men and women. Not all of them did: Thracian women were not as free to ride, fight and govern as the women of some neighbouring nations were. Nor is it sensible to talk about 'equality'; knowing that both women and men were trained to use weapons and to ride as aggressive cavalry does not reveal much about how men and women behaved to one another or divided labour when they were out of the saddle. All the same, the Greeks were right to think that the Scythian-Sarmatian world had an attitude to women and power which was quite unlike their own. They found that attitude horrifying and fascinating.

The second conclusion is that Herodotus, knowing this fascination, catered to it. The Amazon legend had been around for years, always shocking and titillating to Greek male sensibility. What Herodotus heard about Sauromatian society could be appropriated to the Amazon stories by a neat myth about how the Amazons got from Anatolia to the Volga steppe. No doubt the voyage myth already existed somewhere, perhaps in several forms conflated by Herodotus. What matters is that he' Amazonised' the Sauromatians into a mirror-game - a complex one, as Franqois Hartog observes, in which the 'otherness' of the Amazons' original preference for war over marriage is well paraded for the Greek reader, but which ends with a sudden coming-together of those two opposites.

By consenting (in the Herodotus version) to make love with the young Scythian warriors, the Amazons open the way to a new society in which marriage and war no longer exclude one another but may both be practised by a woman. This society — Sauromatia — is in the physical sense formed by the children whom the Amazons bear to the Scythians. But it is also formed by a unique treaty between men and women. The Amazons refuse the patrilocal suggestion of the young Scythians that they should all return to Scythia together, and instead insist that the young men must forsake their own families and follow them across the Don into that empty land 'three days' journey from the Maeotian lake northwards'. In that new place called Sauromatia, the two gender-halves of the community will each retain some of their own distinct rights. The language is to be the male choice of Scythian, which the Amazons (according to Herodotus) never learn to speak correctly. But the rights of women to hunt with or without men and to ride into battle are entrenched for ever. Women also retain control over sexuality and the reproduction of the nation, because the unwritten compact gives priority to Amazon tradition which prescribes that 'no virgin weds till she has slain a man of the enemy; and some of them grow old and die unmarried because they cannot fulfil the law'.

There remains a gap between archaeological evidence and all the various Amazon narratives of Herodotus, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus and the others. It we think that there were Amazons, in some sense, and if we cannot swallow classical explanations of how such societies of female power arose, then we owe ourselves a more 'scientific' set of hypotheses. Many modern savants have been tempted to provide them.

Mikhail Rostovtzeff (i 870-1952), the father of Black Sea historiography, thought that he was looking here at one of the decisive stratifications in human spiritual history. He held the Sauromatians to be a pre-Indo-European population which had preserved the social pattern of matriarchy and the ancient cult of the Mother Goddess. But then 'Semites and Indo-Europeans (Rostovtzeff, writing in 1922, meant Scythians and Sarmatians) brought with them patriarchal society and the cult of the supreme god.' The Mother Goddess none the less survived, in a covert way, and 'the Amazons, her warrior priestesses, likewise survived'. The Sauromatians also preserved older ways: they 'impressed the Greeks by a notable peculiarity of their social system: matriarchy, or rather survivals of it: the participation of women in war and government; the preponderance of women in the political, military and religious life of the community.'

Not all of this has stood the test of time and of another seventy years' excavation. The Sauromatians were not pre-Indo-European: they were Iranian-speakers, the first contingent of the nomad conglomeration we call the Sarmatians to arrive on the Black Sea. And the Scythians — the previous Iranian-speaking wave — were not strikingly more patriarchal. Their cults, as Herodotus recorded, centred on goddesses like Tahiti, the hearth-goddess, or on the 'Great Goddess' so often shown on Scythian goldwork giving a sacred 'eucharist' drink to a king or warlord.

Since Rostovtzeff's time, it has been contended that as pastoral-ism developed from 'primal' Neolithic settled agriculture, it imposed a new division of labour which was sharply to the disadvantage of women: with men constantly in the saddle on the track of the herds, women were confined to domestic work in the tent or the moving wagon. Behind ideas like that lies the enormously influential work of the late Marija Gimbutas, whose work on the origins of the Indo-European language-family has become something of an orthodoxy - and an indispensable text for feminist historians.

Gimbutas believed, roughly, that in south-eastern Europe in the fifth millennium BC there lived a peaceful, highly artistic, matri-lineal population of farmers. This settled late-Neolithic society was then disrupted by the arrival of quite different people from the steppes to the east: warlike, pastoral, nomadic and patriarchal invaders who overthrew the farmers and installed their own more 'primitive' and male-dominated patterns. Gimbutas named these intruders the

Kurgan

tradition, after their custom of steppe burial in mounds, and she identified the

Kurgan

peoples as the core of the 'proto-Indo-European' speakers, spreading out east, west and south from a homeland somewhere in the expanses of the Pontic-Caspian steppe.

This alluring theory would solve a lot of problems for archaeologists and linguistic historians. Even more alluring is its offer of a 'herstory', which would furnish a scientific basis for the association of peace, culture, religious reverence and agriculture with femininity, while categorising war, inequality, philistinism and cattle-ranching as phenomena of male domination.

Not everybody is comfortable with the Gimbutas version, however. There is agreement that there was a 'Late Neolithic Crisis' in south-eastern Europe, and that a densely settled agricultural population gave way to sparser patterns of settlement which were more reliant upon cattle and horses for food, traction and transport. With this change, religious cults or outlooks which involved the manufacture of thousands of clay female figurines were replaced by a different belief system which preferred solar symbols and engraved them upon vertical stone stelae. But there is not much hard archaeological evidence that this revolution was the direct result of a male-led invasion from the steppes. Critics of Gimbutas suggest that the great change could have happened for other, internal reasons. The population may have grown too large to support by crops alone; the introduction of the plough and greater reliance on stockbreeding may by themselves have changed and enhanced the male role.

Whatever the truth here, the Gimbutas link between pastoral nomadism and male-dominated social forms does not help to understand the Indo-Iranian nomads - the Scytho-Sarmatian peoples who began to arrive in the Black Sea steppe nearly three thousand years later. By then, the settled farming peoples of the Mediterranean region were stiffly patriarchal, while nomads and other 'barbarians' often showed signs of matrilineal authority. Timothy Taylor, of the University of Bradford, suggests that the position of Scythian women may have been very free and strong indeed until the pastoral-nomad economy began to make its first contacts with the earliest Greek colonies, in perhaps the seventh century BC, and it was that encounter with Hellenic colonialism which sent the authority of women into decline.