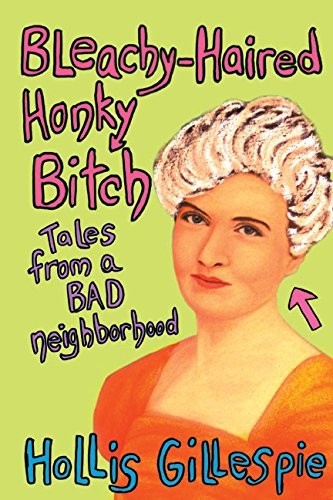

Bleachy-Haired Honky Bitch: Tales From a Bad Neighborhood

Read Bleachy-Haired Honky Bitch: Tales From a Bad Neighborhood Online

Authors: Hollis Gillespie

HOLLIS GILLESPIE

Tales from a Bad Neighborhood

Nothin’ Harder Than a Preacher’s Dick

My Mother and the History of Pornography

Confessions of a Festival Whore

Thank

God you bought this book. Seriously. But even so, to this day I’ve yet to trust the notion it’s not necessary to break your ass to make a buck, so as I write this I’m still employed at my blue-collar job, and my hands are still calloused from lugging stuff. I haven’t thrown away my flight attendant badge and sensible shoes yet and, even scarier, probably never will. The other day my supervisor asked me when I was going to quit, seeing as how I’m a famous writer now and all. I told him, “I ain’t quittin’ ’til they pry the peanuts from my cold, dead fingers, fucker!”

The funny thing is I didn’t know I was writing a book when I started this. Most people have a book lying around in their heads. I, literally, had this one lying around on my closet floor. The chapters were encased in stacks of journals I’d kept while I was going through the complete crap fest that becomes most young adult-hoods fraught with loss and other pain, though with me it started

earlier than normal. I don’t think I would have survived if I hadn’t sat down with a pen and paper (laptops were, like, eleven thousand dollars back then), opened an artery, and just let the poison out every chance I got.

Most of those chances came while I was on layovers. I had faked my way into becoming a German translator in addition to my job as a flight attendant, and every week I flew to one of three countries—Germany, Austria, or Switzerland—and it was in those places, absent any good primetime TV or other mental enemas to feed my need for distraction, where the terror of the truth would hit and I’d have to write. It was a compulsion, an awful compulsion. (Please understand, though, this is not a book about flying so much as it is about getting grounded.)

Then two guys, Patrick Best and Steve Hedberg, publishers of

Poets, Artists & Madmen

in Atlanta, saw something in my stuff, a spark or something, I don’t know. I’m just glad they were looking where I wasn’t. They began running my pieces in their paper, and it all took off from there, especially after Sara Sarasohn, producer of NPR’s

All Things Considered

, began airing my commentaries on her program.

I should mention that nearly everything in this book is true, so long as truth can be trusted to my recollection. A few names have been changed to protect the guilty, but in truth, most of the guilty not only insisted I use their names but also that I spell them correctly and include their phone numbers.

One more thing: I didn’t really call my supervisor “fucker” that day, because if I had, he could have canned my ass like a truckload of tuna. But because of you and lots like you who bought this masterpiece of mine, I am without a doubt absolutely almost positive, kinda, that it hardly would have mattered. So thank God, and thank you too.

If

nothing else, at least I’m living up to my name these days, because I just discovered that in German—make that bad German—my first name means “hellish.”

And my last name is even worse. In German, my last name means “gargoyle.” You would think I would have known about this sooner, because I’ve been a bad German interpreter for twelve years now, but you’d be surprised at how long you can interact within another culture and still keep your knowledge of it neatly limited. Take my mother, who was subcontracted to build missiles for the Swiss in the late eighties. We lived in Zurich for two years, and the only German word she learned was

ja

. She couldn’t even pronounce “Waikiki,” but in my eyes she compensated for her lack of knowledge in this area by the fact that she had a job making bombs.

As an interpreter, my dealings in Germany have mostly been polite business relations, so I’ve never had the need to say the word “hellish” to these people—not unless I was introducing myself anyway.

In front of the Berlin Wall, 1991

You’d think I’d be better at the whole communication thing, considering I’m an official foreign-language interpreter. Fortunately for me I represent people who have no idea I’m using a very broad interpretation of the word “interpreter” to describe my services. As far as they know, I’m translating their words with sparkling precision, but luckily the Germans are pretty tolerant of non-natives who attempt their language, so the interactions usually go off smoothly. Once, an American doctor directed me to ask a German patient when she had had her last bowel movement, and I dutifully turned to the woman and asked her, essentially, “Madame, when was the last time you went to the toilet solidly?”

She answered my question and laughed. My clients must think I am very clever, as I am always making people laugh in their native languages. It is apparently even funnier because I have perfect pronunciation,

and I can turn to a German pharmacist and say without a hint of an accent, “It would please me greatly to purchase medicine for my fluid nostrils,” or to a Spanish taxi driver, while searching for the metal end of the over-the-shoulder safety strap, and tell him, “Pardon me, but I am missing the penis of my seatbelt,” or to an Austrian hotel clerk regarding a beautiful fountain nearby, “Is it possible to acquire a room with a view of the urinating castle?”

It must be hilarious to hear these massacred phrases spoken with the determined clarity of a cowbell. People gather around me and ask me to repeat myself. “Tell us again about the storm in your stomach,” they say, after I translate my account of Montezuma’s revenge, “especially the part about your exploding ass.”

I used to be ashamed at what a bad interpreter I was, until I realized that I get my meaning across, and isn’t that the whole point? And there are people out there who actually think I’m good at this. They

request

me. Every time my work takes me to Europe I still feel giddy, like a stowaway, as if I’ve been able to stave off discovery long enough to fake my way across the Atlantic one more time. Once, while in Munich, I happily hopped along the river’s edge. It was sunny and warm, and I’d just bought a bag of olives at an outdoor market. They were the right kind too—pitted—and I was able to request them by clearly stating, “It would please me to have a hundred grams of the big, boneless black ones.”

The Berlin Wall

My mother in Zurich, 1987

But it fell to a Polish hairdresser to finally enlighten me about my name. I’d been in Munich for a week, participating in a study program that would stuff this half-forgotten, guttural language back into my brain in order to retain my interpreter status, and after class one day I ducked into a salon on Sendlingerstrasse to see if anyone there had time to bleach the hell out of my hair.

I always figured Germany would be a good place to score some good hair highlights. Anyone who’s ever been there can see that all the local women make it their mission to look like they were born and raised on a California beach. Unlike them, though, I actually was born and raised on a California beach, though thirteen years of Atlanta living has seriously eroded my surfer-girl image.

The Polish hairdresser’s name was Barbara, and I didn’t even need an appointment. She simply ushered me to a chair and started slapping some high-test rotgut on my roots. This was my kind of place. In Atlanta, the hairdressers always talk me into new color treatments recently invented by a team of twelve scientists toiling under a glass dome in Finland. The result is usually okay, I guess, but my hair never ends up blond enough. “Can’t we dispense with this fancy crap?” I always ask. “Don’t you have anything back there strong enough to burn the barnacles off a boat?”

American colorists always ignore me and commence their subtle application of a fancy new product. But not Barbara. Barbara’s own hair had been bleached so blonde and so bright that, if you had an

idea to gawk straight at her head, it would be safer to do it from under one of those protective helmets that welders wear. Her own German was bad, but better than mine, because at least she knew the meaning of my first name. She laughed when she heard it, “You come from Hell,

ja

?”

It wasn’t until my scalp was practically bleeding that she finally removed the foils and rinsed the solution from my hair, which, by the way, didn’t fare too well. Much of it had burned off at the roots, leaving little bald patches, and the streaks that remained were as white as lab mice. I would classify the results as less than successful: My scalp looked like it had been bitten by electric eels. I wanted to get out of there fast so that I could assess the damage privately and see if actual sobbing was called for. In my haste, I forgot my umbrella, which prompted Barbara to dash after me down the busy street.

I tried to ignore her but it wasn’t happening. She was calling out my name sweetly, my full name, which she’d read from my credit card, and people were beginning to stop and look around, their curious eyes eventually settling on me. There was nothing else for me to do, so I simply turned and took my place in the world. “Over here, Barbara,” I answered her. She trotted to my side as I stood there, bleach-blond locks and all.

“Hellish Gargoyle,” she smiled, “here you are.”