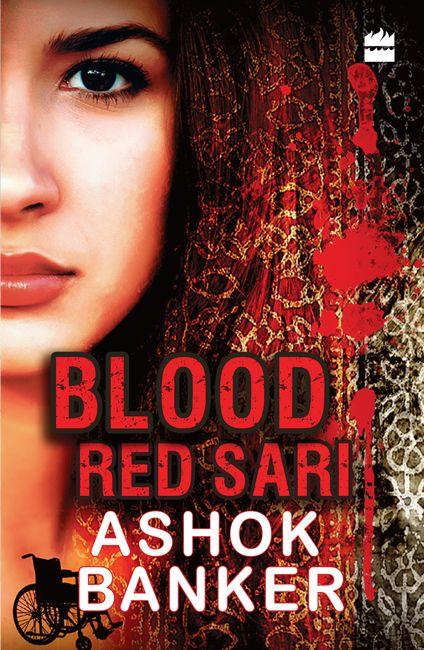

BLOOD RED SARI

Authors: Ashok K Banker

BLOOD RED SARI

Kali Rising

Book 1

Ashok Banker

HarperCollins

Publishers

India

One of the undersides of globalization, human trafficking exists in at least 127 countries … the second most lucrative illicit enterprise in the world after drug trafficking, it is also the fastest growing, with global profits estimated at $44.3 billion USD per year.

– International Labor Organization and United Nations

The number of people held in slavery worldwide is estimated to be between 12 and 27 million, more than at any time in world history. A large proportion of the victims are women and children.

– U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

India’s home secretary Madhukar Gupta remarked that at least 100 million people were involved in human trafficking in India. ‘The number of trafficked persons is difficult to determine due to the secrecy and clandestine nature of the crime.’

India may be the epicenter for human trafficking.

iam redit et Virgo

Translation: Now returns Justice

– Virgil

For

May Smith, grandmother

Sheila D’Souza, mother

Bithika Jain, wife

Yashka Banker, daughter

You made me the boy I was,

The man I grew up to be,

The husband and father I have become,

And the person I aspire to be someday.

And for Willow,

Who taught me that even ‘human’

Is too narrow-minded a classification.

We are all one in our separate skins.

Contents

Kali Pujo

An Appeasement

ON A SEARING AFTERNOON

in May, I caught a tram to the oldest neighbourhood in the city. This is the place for which Kolkata, or Calcutta as the British pronounced it, was named. Kali-ghat, the sacred burning ghat of goddess Kali, which is now just another debilitated inner city neighbourhood, still houses the ancient Kali temple which once formed the centre of the city. It was a Sunday and the streets were quiet and deserted as I got off the tram and walked the last few kilometres through winding cobbled streets. Heat shimmered on the street, making the departing tram seem to levitate before it passed into obscurity. A stray bitch, teats bulging with unconsumed and probably hardened milk, muzzled a pile of rotting watermelon rinds beneath a fruit seller’s handcart. I glimpsed a trickle of blood oozing from her swollen genitalia as I passed by. If the swollen lactose glands didn’t kill her, the haemorrhaging certainly would.

The fruit seller, dozing on the footpath beside the cart, glanced up at me with bulging Bengali eyes, clutching his watermelon knife. The blade had been re-sharpened so many times that it was little more than a crescent sliver. ‘Melon khaabey?’ he asked hopefully. I ignored him and walked on. My destination was the temple, where I meant to offer pujo and express my gratitude to the goddess as promised. I had fasted all day to keep myself pure for the offering.

Kali, in ancient Indian mythology, is one of the infinite forms of Devi, the eternal goddess, repository of all feminine power. The Puranas, literally ‘ancient tales’, tell of a time when the devas, the myriad gods of the Vedic pantheon, were troubled by new enemies. The asuras, their eternal rivals, had four great champions with great powers of destruction. Try as they might, the devas could not defeat the new threat. The demons rampaged and ravaged the realms of the gods and mortals for an eternity until finally, exhausted and at their wits’ end, the devas took refuge in Almighty Brahma, the Creator. The other partners who made up the great Trimurti of the Vedic pantheon – Vishnu the Preserver and Shiva the Destroyer – combined their fury with that of Brahma and the other gods, and a terrible brilliance emanated from each of their faces. Combining with the evanescence of a thousand suns and the spiritual strength of the great sage Katyayana, the devas produced a mighty new champion in the aspect of the goddess Kali. From the deva Mahendra was formed her face. From Agni, Lord of Fire, came her eyes. From Yama, Lord of Death and Dharma, her hair. From Vishnu, the champion of mortalkind and upholder of life, her eighteen hands. From Indra, the general of the army of the devas, her viscera. From Varuna, Lord of the Ocean, her hips and thighs. From Brahma the Creator, her feet. From Surya, the sun god, her toes. From Prajapati, the seed-giver of all life, the teeth. From the eight Vasus, her fingers. From Yaksa, her nose. From Vayu the Lord of the Wind, her ears. And from the ascetic tapasya of Maharishi Katyayana at whose ashram their energies converged, she received her seductive eyebrows.

She was given gifts too – weapons and objects of beauty and great power – by the various devas. When her creation was complete and her armaments assembled, she mounted a lion and went to the highest peak of the Vindhya Range, from whence she launched her campaign of vengeance against the supposedly indomitable asuras – an epic rampage of bloodlust that has few equals even in the blood-spattered annals of Hindu mythology. She was given many names, the foremost among them being Durga, Katyayani, Chamundi, and of course, Kali.

It was to her shrine that I now came, to perform pujo, the prayer ritual to appease and please her. I paused at the entrance to the narrow alley that led to the temple precinct. The last time I had come here, it had been with rage in my heart and a curse on my lips. I had furiously demanded that Kali deliver to me the goal I desired,

or else

. So frustrated had I been at that time, I had threatened the goddess herself. It was the nadir of the worst phase of a not wonderful life.

Now I returned bearing gifts and a light heart. I had in the folds of my sari a gold chain that I intended to give to Kali. I had bought it at a jeweller’s in Park Street for more money than the fruit seller I had walked by would probably earn in his lifetime. The comb, kohl, lip colour and other cosmetics that one customarily gifted to the goddess during the ritual, I would purchase from the pundits at the temple. I also intended to put five thousand rupees into the daanpeti, the donation box of the temple. I would pay to feed all the residents of a girls’ orphanage in Dakshineshwar once a week for a year as well. And of course, how could I forget the sari it was customary to gift the goddess: a sari in a colour that matched her blood-soaked rampage.

There were other offerings too, for I had money to spend and to spare. And limitless gratitude. It had been a good year. A very good year. The more so since it came on the heels of a hard and dangerous life. Not everything that had happened in that year had been good. Some awful, terrible things had taken place. I had made two of the dearest friends I had found in my entire life and lost one of them under circumstances so tragic that it still made me cry in impotent rage when I remembered. There had been a series of events epic enough to rival the tortuously winding story-cycles of ancient Indian Puranas; and when trapped within the deepest, darkest days of that period, I hadn’t expected to come out of it alive. Yet somehow, I had not just survived, I had prospered. Hugely. And now I wanted to show my gratitude, to share the overwhelming sense of relief and joy I now felt, with the goddess I had cursed and abused before leaving Kolkata.

The line was short. The annual Durga Puja festival had just ended – nine days and nights of celebration devoted to nine aspects of the Eternal Goddess – and my fellow Bengalis were mostly home recovering. The woman in front of me in the line was young, barely more than a teenager. She had a Blackberry clutched in her hands and was pressing buttons non-stop, tweeting about her first trip to Kolkata, her first visit to the Kali temple, the fashionable club she was going to party at with her posse that night, how she couldn’t understand why people clung to these ancient pagan customs in this modern age, yada yada yada. The last glimpse I had of her screen, she was updating her Facebook status to continue the grumbling there as well. I resisted the urge to grab her and shake her by the shoulders. In many ways, I was her; I was less than a decade older, perhaps, but in other ways, I was centuries older. And had always been. I was relieved when her turn came and she moved on, head still lowered, punching away.