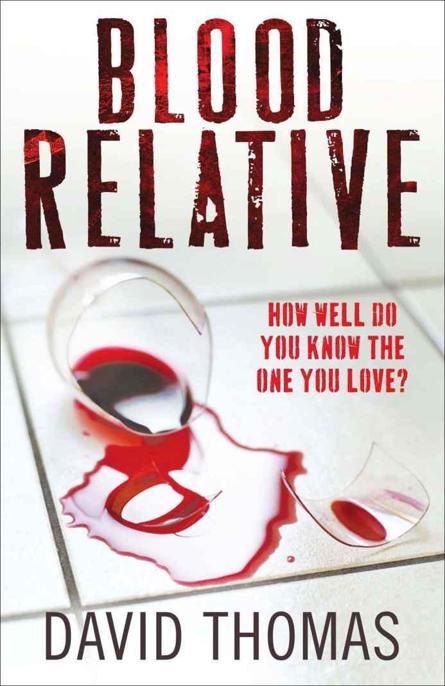

Blood Relative

Authors: David Thomas

David Thomas is a journalist and writer, who already has an ongoing thriller franchise under the name of Tom Cain, published in the UK by Transworld.

Blood Relative

is the first book under his real name.

BLOOD RELATIVE

DAVID THOMAS

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Quercus

55 Baker Street

7th Floor, South Block

London

W1U 8EW

Copyright © 2011 by David Thomas

The moral right of David Thomas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue reference for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85738 797 4

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Swift by Ellipsis Digital Limited, Glasgow

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

FRANKFURT, WEST GERMANY: 1978

Out on the tiny, circular dance floor a blonde and a brunette were dancing to the Bee Gees, giving it their best moves. All they needed now was some male attention. But Hans-Peter Tretow wasn’t about to oblige.

‘Well then, here I am. What do you want?’ Tretow said, turning his back on the girls. He was in his mid-twenties, dressed in a double-breasted suit and a silk kipper tie. His voice still had the brash, even cocky, self-confidence of youth. He leaned against the bar, a glass of beer in his hand, looking at a second man, who was sitting down, his tall, thin, pipe-cleaner body folded onto a stool.

The thin man said nothing. He had rocker sideburns and black hair slicked back. A caramel leather jacket with flared lapels hung from his bony shoulders and the deep shadows in his sallow cheeks darkened still further as he held a hand to his mouth and sucked on the last few usable millimetres of his cigarette.

‘Get on with it,’ Tretow insisted. ‘I’ve got business to do tonight.’

Now the thin man spoke. ‘No, you haven’t.’ He stubbed out his cigarette into a plastic ashtray on the bar. ‘You’ve got to get out. You were followed. They’ve got you nailed.’

Tretow looked angry, as though this were all somehow the other man’s fault. ‘Not possible. I’d have noticed if someone was watching me.’

‘Evidently you did not.’

‘Well then, call Günther, get him to pull some strings. He can make this go away.’

‘No chance: the investigation is too far advanced. Anyone steps in now, people will start wondering why. You’ll have to disappear.’

‘I know a place in Bavaria, right up in the mountains. I could take a break there. Take the wife and kids.’

The thin man tapped another cigarette against the bar, beating out time as he said, ‘You don’t get it, do you? This isn’t about taking a holiday. You’ve got to disappear … completely … now.’

‘Don’t tell me what to do!’

‘All right then, go to the mountains. Then wait to see who finds you first – the cops, or whoever Günther sends to silence you. You’ll never make it to the inside of an interview room. You know too much. He won’t let it happen.’

‘He wouldn’t dare!’ Tretow’s voice was still assertive, but there was more bluster than certainty in it now.

The thin man reached out and gripped Tretow’s lower arm hard. ‘Listen to me, you arrogant sack of crap. You must have known this could happen. You’ve got an escape plan, right?’

Tretow nodded.

‘Well then,’ said the thin man. ‘Use it.’

On leaving the club, Tretow did not return home to his wife Judith and their two infant children. Instead, he drove his smart new Mercedes 250C coupé to a grimy, run-down side street lined with lock-up garages. He opened one of them up and drove in, parking next to another car, an unwashed ten-year-old Volkswagen Beetle, painted beige: as anonymous and nondescript as any vehicle in Germany.

At the back of the unit a door led to a small, dirty, foul-smelling toilet. Tretow reached behind the low-level cistern. He pulled at two strips of black masking tape and released a clear plastic bag no more than twenty centimetres square and then tucked it inside the Beetle’s spare wheel. From a storage cupboard covered in flaking green paint Tretow removed a workman’s boiler suit, boots and donkey jacket. He put these on in place of his smart suit and tie. Then he drove the Volkswagen out of the unit, locked the doors behind him and started driving.

When Tretow reached the outskirts of the city, following the signs to the A45 autobahn, north towards Marburg, it was twenty-seven minutes past one in the morning.

He drove for two and a half hours. For three hours after that he slept in the car park of a service area beside the autobahn. When he woke, he set off again, heading east.

It was now seven in the morning. In Frankfurt, a detective coming to the end of a fruitless surveillance shift was reporting back to his boss that Tretow had not come home all night. Voices were raised, increasingly agitated phone calls were made and police across the state of Hesse were told that Hans-Peter Tretow was now, officially, a fugitive from justice. Local railway stations and airports were also informed. It would, however, take a little time to coordinate a wider, nationwide alert.

In all the fourteen hundred kilometres of border between West and East Germany, there were just three points at which motorists could pass from one country to the other. One of them was at Herleshausen, eighty kilometres west of the city of Erfurt. Tretow’s VW joined the long line of cars and trucks waiting to enter the communist dictatorship. All the drivers, passengers and vehicles were inspected by East German border control officers from Directorate VI of the Ministry of State Security, otherwise known as the Stasi. Tretow was ready. He had both his passport and Federal Identity Card. He explained that he was travelling to West Berlin where he hoped to get work on a construction site.

In order to get to there, however, first he had to cross 370 kilometres of East Germany. For this he needed a visa, which was issued not by the day or month but by the hour and minute. The East German authorities did not want anyone stopping by the side of their autobahns to pick up clandestine passengers who might wish to escape to the West. Drivers were therefore ordered to proceed down the road at a continuous eighty kilometres per hour. At this rate, the journey was calculated to take no more than four hours and forty minutes. That was, therefore, the amount of time for which Tretow’s visa would be valid. Should he arrive at the Drewitz-Dreilinden checkpoint on the south-west outskirts of Berlin any later than this, the Stasi would want to know why.

Tretow waited his turn in the interminable queue before he was finally issued with his visa and set off again. It was now nineteen minutes past ten. In Frankfurt a formal alert was being sent to West Germany’s Federal Border Guard, requesting Tretow’s immediate apprehension and arrest. The checkpoints on the western side of the Berlin Wall were included in this alert. If Tretow attempted to enter West Berlin he would be caught and returned to Frankfurt by air.

But Tretow had other plans. When he reached Drewitz-Dreilinden he joined one of several lines of vehicles backing up along the autobahn. Each line crawled towards a raised platform. On each platform stood six white wooden passport control booths, one per car, occupied by uniformed personnel.

Up ahead of the checkpoint the Berlin Wall was clearly visible, topped by barbed wire and supplemented at intervals by guard towers filled with machine-gun-toting soldiers. Beyond the wall lay an open killing field strewn with anti-personnel mines and tank-traps, and patrolled by guards with attack dogs. Beyond that space stood a second wall. Many civilizations in history, from the Chinese to the Romans, had built mighty walls to keep their enemies out. None had ever gone to such lengths to keep their own people in.

Tretow inched forward until the Beetle was lined up alongside one of the booths. As he handed over his papers he said, ‘I wish to defect.’

The passport control officer frowned, wondering whether this shabbily dressed worker in his beat-up car was playing some kind of a joke. Before he could respond, Tretow spoke again. ‘I am seeking political asylum,’ he said. ‘In the East.’

TUESDAY

York, England: now

My wife Mariana was the most beautiful woman I’d ever laid eyes on and yet she was so bright, so complex, so constantly capable of surprising me that her beauty was almost the least interesting thing about her. Six years we’d been together and I still couldn’t believe my luck.

That morning, when it all began, I’d told her that my brother Andy was coming to stay for the night. I said we were planning to go out for a quick pint before supper.

‘It’s Mum. Andy’s going over to see her today. He’s bothered about the way she’s being treated. He just wanted to talk about it with me and he knows you never got on with her, so … hope you don’t mind.’

I must have had a particularly sheepish look on my face because Mariana laughed in that wonderful way of hers, so carefree and full of life, but always with that tantalizing hint underneath it that she knew something I didn’t: ‘That’s fine. You guys go and have your brother-talk,’ she said, just the faintest of accents and oddities of grammar betraying her German origins. ‘I will stay home and cook, like a good little hausfrau.’

Mariana giggled again at the absurd idea that she, of all people, could ever be the meek, submissive wife. I just stood there in the kitchen grinning like a fool: but a very happy fool.

My name’s Peter Crookham, I’m an architect and I’m forty-two years old. If I have a distinguishing feature it’s my height. I’m tall, six-three in my stockinged feet. I played rugby at school and did a bit of rowing at university: nothing serious, just my college eight. These days, I’m like every other middle-aged guy in the world trying to get his act together to go to the gym or stagger off on a run, wondering why his trousers keep getting tighter. Those love-handles: where did they come from? I have pale-blue eyes and mousey-brown hair, just starting to thin. Last summer for the first time I got a small patch of sunburn on my scalp, the size of a fifty-pence piece. ‘Poor bald baby,’ teased Mariana as she massaged the after-sun cream into my bright pink skin.

As for my face, well, when women wanted to say nice things about me they never used to describe me as hunky or handsome. They told me I had a kind smile. I was never anyone’s dirty weekend. I was the nice, reliable, unthreatening type of guy that a woman didn’t feel embarrassed to be seen with at a party. But she wouldn’t be worrying herself sick that some other girl was going to make a beeline for me, either.

Basically, I’m Mr Average. Or at least I was. Then Mariana came into my life.

Twelve hours had passed since I’d told her about Andy and now the pint would have to wait. I’d been held up on a site visit in Alderley Edge, Cheshire, eighty-odd miles from our place outside York. Heading home along the M62 I called her on the hands-free. A combination of snow-flurries, roadworks and speedcams had slowed the traffic to a crawl: an all-too familiar story for a Tuesday night in February. ‘I’m definitely going to be late,’ I said. ‘Looks like I’ll have to scrap that drink with Andy. Is he there yet?’

‘Yes, he is here,’ Mariana said. There was something strange about her voice: a flatness that I’d never heard before. Or maybe it was just a bad connection.

‘Can I have a word with him?’

‘No,’ she said, ‘he cannot talk.’

‘That doesn’t sound like Andy,’ I said, smiling to myself. The hard part was usually getting him to stop talking, particularly if he had a chance to take the mick out of me. ‘What’s he up to?’