Bloodied Ivy (21 page)

Authors: Robert Goldsborough

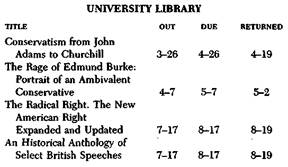

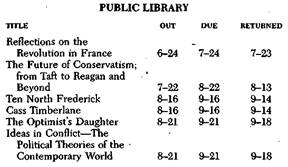

“Archie, you mentioned something earlier about Markham having kept a log of the books he checked out of the library.”

“I’ll be damned, I didn’t know you were listening. Yeah, I told you about his library books, his clothes, and his—”

“I’d like to see that list of books, please.”

By that, Wolfe meant he wanted a printout. It would have been easier, of course, for me to simply pop the disk in and have him read it on the screen, but as I learned in the months we’d had the computer, he refused to use the terminal. He didn’t trust anything that wasn’t on the desk in front of him in black and white.

I briefly considered tweaking him again about this new idiosyncrasy, but checked myself. However strange the request, he actually was doing something. This was progress. I put the

LIBRARY BOOKS

disk into the computer and activated the printer, which chattered for a little under a minute, spitting out the list. I tore off the sheet of paper and walked it to Wolfe’s desk, laying it in front of him with a mild flourish:

Wolfe studied the list, scowled, and tossed it aside. “His checking account now, please.”

“Going to see if he wrote a check for those overdue books in August?” I asked. I began to suspect this was merely an exercise to keep me from harassing him. Or worse, maybe it was the only idea he had, and he was firing blindly, hoping to hit something. “Here’s his check ledger since the first of the year,” I said three minutes later, handing him another printout. “Balance as of last entry, eleven hundred ninety-six dollars, fifty-five cents. Do you want his other finances, too?”

Wolfe shook his head as he scanned the list of checks, then tossed it aside, too, and rose, heading for the door.

“That’s it?” I asked. “No more printouts? No orders for me?”

“Archie, it is now eleven-thirty-five,” he said, stopping in the doorway to the hall. “Tomorrow is soon enough to plan a course of action. Good night.”

I started to call after him that it was never too soon to plan a course of action, but before I could get my phrasing just right, I heard the banging of the elevator door, followed by the whir of the motor as it labored to carry its load of a seventh of a ton upstairs.

I sat at my desk for several minutes, sipping the last of the Scotch and pondering the day’s events. A second death had been visited upon Prescott. A millionaire—or maybe he’s a billionaire—had come to the house offering to pay triple the fee we were working on and got told thanks, but no thanks. And a beautiful woman looked right through me as though I were invisible. And after all this, the resident genius pulls a Scarlett O’Hara and tells me tomorrow is another day. Is it any wonder that I indulge myself in an occasional sip of something stronger than milk?

I

HAD AN INKLING THAT

Monday would be more than a little hectic, and my inkle was right. I was in the kitchen attacking link sausage, scrambled eggs, muffins, and coffee at eight-fifteen when the phone rang. “It’s Mr. Cohen,” Fritz said, cupping the receiver. “He sounds excited.”

“He always sounds excited; it’s an occupational hazard. Tell him I’ll call him as soon as I finish eating.”

Fritz repeated my instructions into the phone, then listened and said “no” twice before hanging up. “He wasn’t happy, Archie. He tried to get me to interrupt you while you were eating, but of course I would not do that.”

“Of course. Fritz, I don’t say this often enough—you are a gem.” He blushed and turned his back to me as he went on with preparations for lunch. Fritz Brenner gets easily embarrassed by compliments, but don’t think for a moment that he doesn’t like to get them, whether they’re about his cooking or anything else he does in the brownstone, which includes playing waiter, butler, housekeeper, phone answerer, and all-around indispensable man.

Lon undoubtedly had seen the story on Gretchen Frazier’s death in the morning edition of the

Times

. Six paragraphs long, it was on page fourteen in the first section. It said her body was found at the bottom of Caldwell’s Gash by two joggers a little after seven Sunday evening, which would have put it just about sunset. Death was attributed to “massive head injuries” apparently suffered in the 125-foot fall, according to the county medical examiner. The

Times

quoted Prescott Police Chief Carl Hobson as saying “Foul play has not been ruled out. We are investigating.” And of course mention was made that Gretchen was an honors graduate student whose adviser, Hale Markham, had been found dead in similar circumstances in the same location a few weeks earlier. One further irony the paper pointed out: A fence along the rim of the Gash at the point where both Markham and Gretchen went over the edge was to have been installed today.

I dialed Lon and got him on the first ring. “Archie, what in the name of Mario Cuomo is happening up at Prescott? Don’t think I’ve forgotten your supposedly innocuous call the other day. And then I pick up this morning’s

Times

and read about that coed. Something tells me we’re not talking coincidence here.”

“Something tells me you’re right, friend. I can’t say much right now, mainly because I don’t know much.”

“And you call yourself a friend? Oh, come on, Archie. Give me something.”

“Okay, but not for publication yet. If any of what I’m about to tell you gets into print now, I’ll clam up later, when the real story develops, assuming there is one. Got it?”

“Got it,” Lon said grimly.

“Okay, here’s the picture, at least as much of it as I have: We have a client—name, Walter Cortland. The guy’s a political science prof at Prescott and was a disciple of Markham’s. And fiercely loyal to Markham, at least to hear him tell it.

“Anyway, Cortland called last Monday and came to see us Tuesday, saying he was sure Markham had been helped over the edge of that poor-man’s Grand Canyon on the campus. He couldn’t—or wouldn’t—nominate anybody as the shover, though. To make a long story short, I’ve been up to Prescott three times, and Wolfe has even been there himself, and—”

“Wolfe went to Prescott?” Lon wheezed in disbelief.

“Don’t interrupt—it’s impolite. Yes, the man himself got a taste of contemporary college life, and discovered, incredible as I know it must sound, that he likes the brownstone better. To continue, we talked to a number of people up there, including Gretchen Frazier. She was a student of Markham’s, as this morning’s

Times

points out, and it’s also highly possible that their relationship was something more than just teacher and pupil. Several of the others we talked to were considerably less enthusiastic about him. As you recall, when I asked you about him a few days ago, you said he had a reputation for being irascible, contentious, and not exactly popular with other faculty members. With the exception of one woman in the History Department, your report seems accurate based on our experience.”

“It would be a woman,” Lon remarked. “I’m not surprised, given his supposed reputation with the ladies.”

“Uh-huh. At this point, Wolfe is mulling the situation over, at least I like to tell myself he is, but if he’s getting ready to throw a net over someone, he isn’t sharing it with me.”

“That’s it?” Lon asked.

“That’s it for now. Film at eleven.”

“Very funny. Okay, Archie, I’m good for my word—you know that. But when something happens, remember your old poker-playing buddy.”

“How could I forget? The way I figure it, through the years, my contributions have probably paid for that knockout white fur I saw your wife wearing last winter.” Lon answered with a word best omitted from this report, and I hung up, turning back to the

Times

piece on Gretchen, which I scissored out of the paper and slipped into the top center drawer of my desk. No sooner had I finished than the phone rang. It was Cortland, who sounded even more breathless than Lon.

“Mr. Goodwin, I’ve just returned home from police headquarters,” he huffed. “They telephoned me early this morning and requested my presence—demanded it, actually. I asked if I could defer the visit until afternoon, but the man on the other end was adamant. He said someone could come for me in a car, and I told him, ‘No thank you.’ After all, who wants a police vehicle pulling up in front of their house, especially with the meddlesome neighbors I’ve got? So I went on foot—it’s only a little over four blocks. And do you know what transpired when I got there?”

“Sure. They grilled you.”

“What? Oh—grilled. Interrogated. Yes, that’s just what they did. And none too nicely, I’d like to tell you. There were two of them, a lieutenant named Powers and another cretin, and they bombarded me with a lot of rude questions about Gretchen Frazier and Hale. They even asked me if I’d ever been…

involved

with Gretchen, if you can conceive such outrageous effrontery!”

“Had you?”

“I’m afraid I don’t find that the least bit humorous, Mr. Goodwin. The answer, of course, is no. The police also insisted on ascertaining where I was yesterday at the time they calculate that poor girl went into the Gash. I told them the truth, of course—that I was home alone.”

Academics seem to spend a lot of time at home alone—when they’re not bumping one another off. “When did they say that was?”

“Lieutenant Powers declared it was sometime between five-thirty and when she was found. I was at home every bit of that time.”

“How did you find out last night that she had died?”

“I received a call around eight-thirty or so from Orville Schmidt. He said he had just learned from somebody, Campus Security, I believe it was. It’s incredible how speedily word flies in a place like Prescott. Anyway, he said he was calling each faculty member in the department to tell them personally. He seemed understandably appalled and said this would be horrific for the department and the university.”

“Sounds like Leander Bach,” I said.

“What?”

“Nothing. What else did the police ask you?”

“What

didn’t

they ask? They were obsessed in their desire to know how well Hale and Gretchen knew each other. As much as the question offended me, I said I thought she admired him as a great teacher and he was excited by her intellectual potential—both of which I firmly believe constituted the total basis of their friendship. They asked if Hale had enemies on campus, and I said I was aware of none, beyond the usual petty jealousies.”

“Did you tell them about the feuds with Schmidt and Greenbaum? And the business with Potter and Bach over the bequest to the school?”

“I did,” he said after several seconds. “Although they already knew about the Bach brouhaha because of all the commotion it generated at the time.”

“How did the police leave things after they finished talking to you?”

“They told me to be available in the event that they needed to talk to me again. And they weren’t very polite about that, either, I might add.”

“Murder, or even the suspicion of murder, tends to make cops feisty,” I said, “whether they’re in New York or New Paltz. I wouldn’t be too hard on them.”

“They behaved rudely—boorishly,” Cortland whimpered, “and I can’t forgive that in anyone, let alone public employees. Our taxes are what pay their salaries, after all.”

“I’m sure they get reminded of that often enough. But back to the subject at hand: Mr. Wolfe is at work, believe me. I’m confident that he’s on the brink of solving this thing, and I’ll keep you apprised of every development.”

Cortland sounded doubtful as we said good-bye, and for that matter I was pretty doubtful myself. Lying to clients always bothered me for at least fifteen minutes after I did it, which probably reflects my small-town, middle-class Ohio origins.

If I

had

told Cortland the truth, it probably would have sounded something like this: “I’m terribly sorry, but Mr. Wolfe at present is not in the proper frame of mind to do any thinking about the problem for which you have engaged him and are paying handsomely. He has his orchids to worry about, and his reading—he’s plowing through three books right now—and his crossword puzzles, not to mention the time he is forced to spend overseeing our chef, Mr. Brenner, to ensure that the proper types and amounts of seasonings and sauces are added to the gourmet dishes that comprise such a big part of Mr. Wolfe’s life. So you can see that this doesn’t leave a lot of time for detecting, which after all is something Mr. Wolfe only dabbles in, despite its being his primary source of income. I ask your patience in this matter, and I can assure you that Mr. Wolfe will get back to work on your problem soon, quite possibly as early as next week, but certainly no later than the week after that.”