Bloody Crimes (6 page)

Colonels John Taylor Wood and William Preston Johnston, “gentlemen of high character, cultivated minds, and pleasing address,” agreed. “They were quiet,” recalled Mallory, “but professed to be confident, saw much to deplore, but no reason for despair or for an immediate abandonment of the fight.” Colonel Frank Lubbock, the former Texas governor and Davis’s favorite equestrian riding partner during the war, entertained his fellow travelers with wild Western tales. Mallory summed him up with a pithy character sketch: “An earnest, enthusiastic, big-hearted man was Colonel Lubbock, who had seen much of life, knew something of men, less of women, but a great deal about horses, with a large stock of Texas anecdotes, which he disposed of in a style earnest and demonstrative.”

The most important contributor to the jolly mood might have been Secretary of the Treasury Trenholm. Although ill, semi-invalid, and unable to regale his colleagues, Trenholm contributed an essential ingredient to the cheery mood aboard the train: a seemingly inexhaustible supply of “old Peach” brandy. “As the morning advanced our fugitives recovered their spirit,” testified Mallory, “and by the time the train reached Danville…all shadows seemed to have departed.”

Lincoln was unaware of what was happening in Richmond

throughout the night. But in the morning he telegraphed Edwin M. Stanton in Washington, informing him that the Confederacy had evacuated Petersburg, and probably Richmond too.

Head Quarters Armies of the United States

City-Point

April 3. 8/00

A.M.

1865

Hon. Sec. of War

Washington, D.C.

This morning Gen. Grant reports Petersburg evacuated; and he is confident Richmond also is. He is pushing forward to cut it off if possible, the retreating army. I start to him in a few minutes.

Lincoln

Soon Lincoln would go to Petersburg to meet with General Grant. But before he departed, he received a telegraph from his son Robert, informing him that he was awaiting his father at Hancock Station.

News traveled quickly. In New York City, Southern sympathizers, including the celebrated Shakespearean actor John Wilkes Booth, mourned the fall of the Confederate capital. New York had never been a stronghold for Lincoln or the Union. Indeed, in 1863, rioting New Yorkers who opposed the military draft had lynched blacks in the streets and become so depraved that they attacked and burned the Negro orphanage. Troops had to put down this mad rebellion. Walt Whitman scorned Gotham as a disloyal citadel of “thievery, druggies, foul play, and prostitution gangrened.”

All day April 3, Washington, D.C., celebrated the fall of Richmond. The

Evening Star

captured the joyous mood: “As we write Washington city is in such a blaze of excitement and enthusiasm as we never before witnessed here…The thunder of cannon; the ringing of bells; the eruption of flags from every window and housetop,

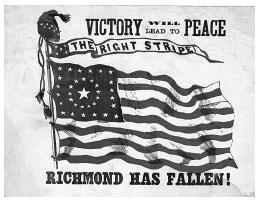

BROADSIDE FROM THE FIRST WEEK OF APRIL 1865.

the shouts of enthusiastic gatherings in the streets; all echo the glorious report. RICHMOND IS OURS!!!”

The news spread through the capital, reported the

Star,

by word of mouth: “The first announcement of the fact made by Secretary of War Stanton in the War Department building caused a general stampede of the employees of that establishment into the street, where their pent-up enthusiasm had a chance for vent in cheers that would assuredly have lifted off the roof from that building had they been delivered with such vim inside…The news caught up and spread by a thousand mouths caused almost a general suspension of business, and the various newspaper offices especially were besieged with excited crowds.”

Lincoln’s favorite newsman, Noah Brooks, who was set to begin his new job soon as private secretary to the president, recorded the moment: “The news spread like wildfire through Washington…from one end of Pennsylvania Avenue to the other the air seemed to burn with the bright hues of the flag. The sky was shaken by a grand salute of eight hundred guns, fired by order of the Secretary of War—three hundred for Petersburg and five hundred for Richmond. Almost by magic the streets were crowded with hosts of

people, talking, laughing, hurrahing, and shouting in the fullness of their joy…”

The Union capital celebrated without President Lincoln, who was still in the field. While Washington rejoiced, Edwin Stanton worried about Lincoln’s security. He had always believed that Lincoln did not do enough to assure his own safety. No longer so eager to have Lincoln at the front, Stanton urged him to return to Washington. Lincoln’s telegram advising Stanton that he would visit General Grant at City Point on April 3 alarmed the secretary of war, who urged the president not to go to the front lines. “I congratulate you and the nation on the glorious news in your telegram just recd. Allow me respectfully to ask you to consider whether you ought to expose the nation to the consequence of any disaster to yourself in the pursuit of a treacherous and dangerous enemy like the rebel army. If it was a question concerning yourself only I should not presume to say a word. Commanding Generals are in the line of duty in running such risks. But is the political head of a nation in the same condition.”

D

avis did not arrive in Danville until 4:00

P.M.

on April 3. Much had happened in Richmond, and elsewhere, while he was languishing aboard the train. It had taken eighteen hours to travel just 140 miles. The train had averaged less than ten miles per hour, and at some points, especially on uphill grades, it could barely move at all. Sometimes the train stopped completely. This sorry performance demonstrated the lamentable state of the Confederate railroad system. The plodding journey from Richmond to Danville made clear another uncomfortable truth. If Jefferson Davis hoped to avoid capture, continue the war, and save the Confederacy, he would have to move a lot faster than this. Still, the trip had served its purpose. It had saved, for at least another day, the Confederate States of America. If Davis had allowed himself to be captured or killed on April 2 or 3, the Civil War

might have ended the day Richmond fell. By fleeing, Davis ensured that the fall of the city was not fatal to the cause. As Mrs. Robert E. Lee, who endured the occupation, said, “Richmond is not the Confederacy.”

The government on wheels unpacked and set up in Danville on the afternoon and evening of April 3. For two reasons, Davis hoped to remain there indefinitely, depending upon word of General Lee’s prospects. First, as long as Davis stayed in Danville, he was maintaining a symbolic toehold in Virginia. He abhorred the idea of abandoning the Confederacy’s principal state to the invaders. If circumstances forced a retreat from Danville, Davis would have no choice but to continue south and cross the North Carolina state line. Second, Danville put him in a better position to send and receive communications. Without military intelligence, it would be difficult to issue orders or coordinate the movements of his armies. It would be hard for his commanders to telegraph the president or send dispatch riders with the latest news if he stayed on the move, if they did not know where to find him, and if they had to chase him from town to town. In Danville he had everything he needed to continue the war.

Secretary Mallory rattled off a checklist of their resources: “Heads of departments, chief clerks, books and records; Adjutant General of the army Samuel Cooper with the material and personnel of his office, all the essential means for conducting the government, were here; and so able and expert were these agents, that a few hours only, and a half-dozen log cabins, tents, and even wagons, would have sufficed for putting it in fair working order.”

The inhabitants of Danville had received advance word that their president was coming, and a large number of people waited at the station for his train. They cheered Jefferson Davis when he disembarked from his railroad car. With fine Virginia hospitality, leading citizens opened their homes to the president and the other dignitaries. Colonel William T. Sutherlin, a local grandee, considered it

an honor for his town to host the Confederate government, and he offered the president, Trenholm, and Mallory accommodations in his own home.

The remaining cabinet members received similar offers from other citizens. Soon, refugees from Richmond and elsewhere flooded into Danville, overtaxing the town’s hospitality and housing. Many of them, including women, slept in railroad cars parked on sidings near the tracks, obtained their food from Confederate commissaries, and cooked their meals in the open. The new, temporary capital could never match the grandeur of Thomas Jefferson’s city of the seven hills, but Danville symbolized the Confederacy’s resilience. As long as Davis was able to sustain his government from this humble outpost, the cause was not lost.

As Davis settled into Danville, Abraham Lincoln reassured his secretary of war that he was safe and had survived the day. Lincoln had ignored Stanton’s warning. The end of the war was near. Nothing could stop him from traveling to the front lines of the Union army. But he thanked Stanton for his concern—after the trip:

Head Quarters Armies of the United States

City-Point,

April 3. 5

P.M.

1865

Hon. Sec. of War

Washington, D.C.

Yours received. Thanks for your caution; but I have already been to Petersburg, stayed with Gen. Grant an hour & a half and returned here. It is certain now that Richmond is in our hands, and I think I will go there to-morrow. I will take care of myself.

A. Lincoln

If Lincoln’s visit to Grant had worried Stanton, this proposed trip by the president to Richmond, a city still smoldering, inhabited

by thousands of secessionists who hated Lincoln, must have given him fits.

A

s darkness approached Washington, D.C., the celebrations became more intense, even wild. Lincoln missed it all, but his friend Noah Brooks recorded his memories of the evening. “The day of jubilee did not end with the day, but rejoicing and cheering were prolonged far into the night. Many illuminated their houses, and bands were still playing, and leading men and public officials were serenaded all over the city. There are always hosts of people who drown their joys effectually in the flowing bowl, and Washington on April third was full of them. Thousands besieged the drinking-saloons, champagne popped everywhere, and a more liquorish crowd was never seen in Washington than on that night.”

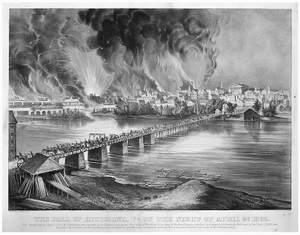

In Richmond, a different sun set on the first day of Union occupation. The ruins still smoked. As in Washington, people filled the streets. Soon the printmaker Currier & Ives, which had made a specialty of publishing images of American urban disasters—especially great conflagrations—would immortalize this night of fire and destruction in an oversized, full-color panoramic print suitable for framing. For customers on a budget, the Currier firm also published a less expensive, smaller version of Richmond in flames.

Constance Cary reflected on all she had seen that day. “The ending of the first day of occupation was truly horrible. Some negroes of the lowest grade, their heads turned by the prospect of wealth and equality, together with a mob of miserable poor whites, drank themselves mad with liquor scooped from the gutters. Reinforced, it was said by convicts escaped from the penitentiary, they tore through the streets, carrying loot from the burnt district. (For days after, even the kitchens and cabins of the better class of darkies displayed handsome oil paintings and mirrors, rolls of stuff, rare books, and barrels of sugar and whiskey.) One gang of drunken

THE FAMOUS CURRIER & IVES PRINT OF RICHMOND BURNING, APRIL 2, 1865.

rioters dragged coffins sacked from undertakers, filled with spoils…howling madly.”